Birds can fly due to a combination of specialized anatomical features, powerful muscles, and aerodynamic principles that allow them to generate lift, thrust, and control in the air. The key to understanding how can birds fly lies in their lightweight yet strong skeletons, specially shaped wings, and the mechanics of flapping flight. These adaptations—such as hollow bones, fused skeletal structures for rigidity, and feathers arranged in an airfoil shape—enable birds to overcome gravity and propel themselves through the atmosphere efficiently.

Anatomical Adaptations That Enable Flight

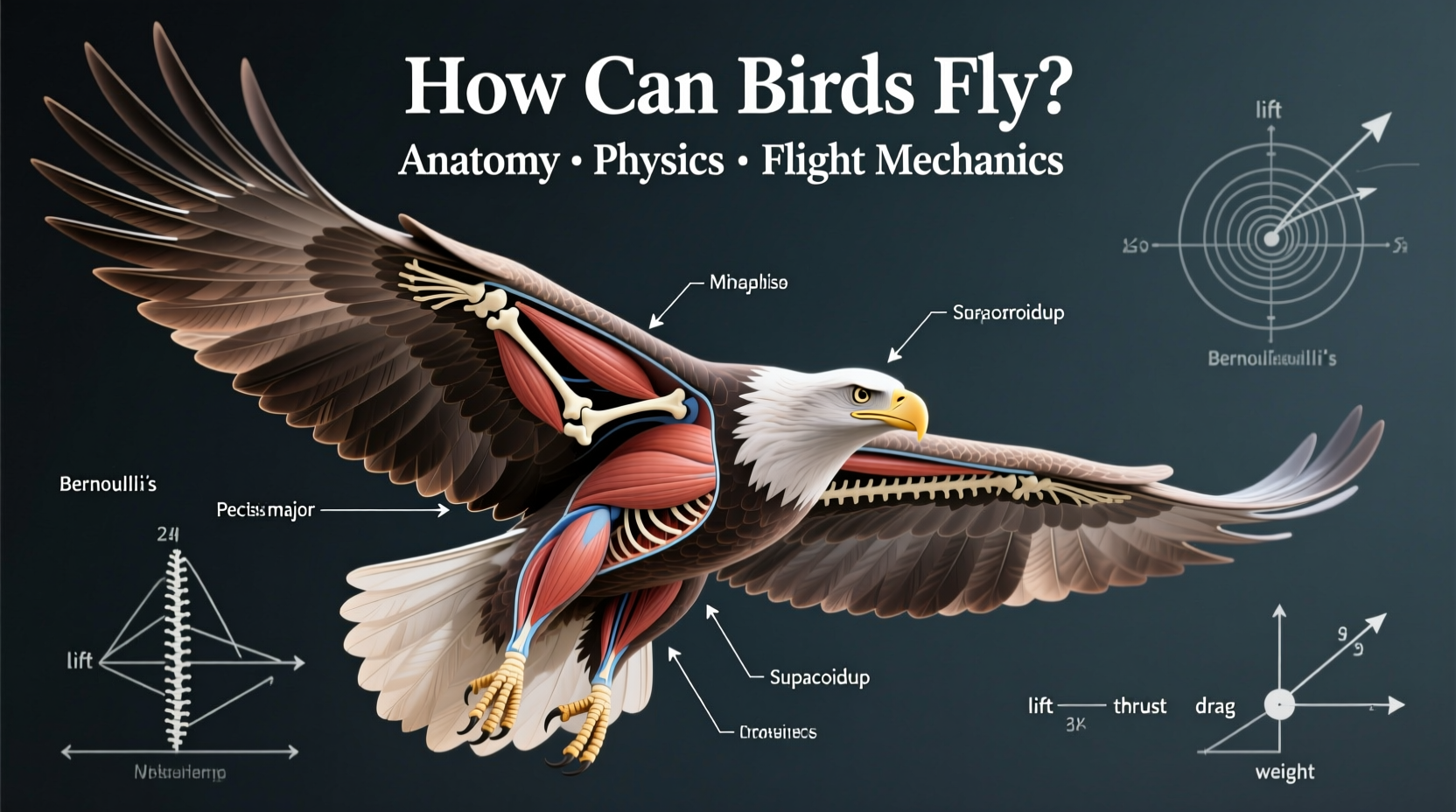

The ability of birds to fly begins with their unique anatomy, which has evolved over millions of years to optimize aerial locomotion. One of the most critical components is the bird’s skeleton. Unlike mammals, birds have hollow bones filled with air sacs connected to their respiratory system. This not only reduces overall body weight but also improves oxygen delivery during flight—a necessity given the high metabolic demands of sustained flying.

In addition to being lightweight, avian skeletons are highly fused in key areas such as the spine and pelvis, providing structural rigidity needed to withstand the forces generated during wing beats. The keel, or sternum, is another crucial adaptation. It serves as an anchor point for the large pectoral muscles responsible for powering the downstroke of the wings. In fact, these flight muscles can make up 15% to 25% of a bird’s total body mass, especially in strong fliers like pigeons and migratory species.

Feathers play an indispensable role in flight. Contour feathers on the wings and tail are stiff and asymmetrically shaped, forming an airfoil surface that generates lift when air moves faster over the curved upper surface than the lower one—this is known as Bernoulli’s principle. Primary feathers at the wingtips provide thrust, while secondary feathers along the inner wing contribute more to lift. Tail feathers act as rudders and brakes, allowing precise maneuvering and controlled landings.

The Physics Behind Bird Flight

To understand how can birds fly from a physics standpoint, we must examine the four fundamental forces acting on any flying object: lift, weight (gravity), thrust, and drag. Birds counteract gravity by generating lift primarily through wing movement and shape. When a bird flaps its wings downward, it pushes air down, creating an upward reactive force—lift. During the upstroke, many birds fold or twist their wings slightly to reduce negative lift and minimize energy loss.

Airfoil-shaped wings enhance this process. As air flows over the top of the wing, it travels faster than the air beneath, resulting in lower pressure above and higher pressure below—the pressure differential produces lift. This same principle applies to airplane wings, though birds have the advantage of dynamic control, adjusting wing shape and angle mid-flight for maximum efficiency.

Thrust, the forward force that propels a bird through the air, comes from the powerful contraction of the pectoralis major muscle during the downstroke. Some birds, like hummingbirds, can even rotate their wings in a full circle, enabling them to hover, fly backward, or move sideways—something no fixed-wing aircraft can do without special engineering.

Drag, the resistance caused by air friction, is minimized by streamlined body shapes and smooth feather coverage. Birds tuck their legs and feet close to their bodies during flight to reduce drag, and many adopt V-formations during migration to take advantage of upwash vortices created by the bird ahead, reducing individual energy expenditure by up to 20%.

Types of Flight and Avian Diversity

Not all birds fly in the same way, nor do all birds fly at all. There are several distinct flight styles adapted to different ecological niches:

- Flapping flight: Used by most passerines (songbirds), pigeons, and waterfowl. Requires continuous muscular effort and is effective for short bursts or moderate distances.

- Soaring and gliding: Employed by raptors like eagles and vultures, which use rising thermal currents to gain altitude without flapping. Their broad wings and long primary feathers maximize lift with minimal energy cost.

- Hovering: Perfected by hummingbirds, which beat their wings up to 80 times per second. This allows them to remain stationary in front of flowers while feeding on nectar.

- Dynamic soaring: Practiced by albatrosses over open oceans. They exploit wind gradients just above wave surfaces to travel vast distances with almost no flapping.

Conversely, some birds have lost the ability to fly entirely through evolution. Examples include ostriches, emus, kiwis, and penguins. These species typically inhabit environments with few terrestrial predators or have adapted to alternative modes of locomotion—like running or swimming—where flight would be energetically inefficient or unnecessary.

Biological Trade-offs and Energetics of Flight

Flight is incredibly energy-intensive. A small bird like a sparrow may consume oxygen at a rate ten times higher during flight than at rest. To support this demand, birds have evolved one of the most efficient respiratory systems in the animal kingdom. Unlike mammals, birds have unidirectional airflow in their lungs, meaning fresh air passes through the gas-exchange surfaces continuously, aided by a network of air sacs throughout the body. This ensures a constant supply of oxygen, essential for aerobic metabolism during prolonged flights.

Diet also plays a role. Migratory birds often undergo hyperphagia—excessive eating—before long journeys to build fat reserves. For instance, the blackpoll warbler doubles its body weight before crossing the Atlantic Ocean nonstop from Canada to South America, a journey lasting up to 72 hours.

Despite its advantages—such as escaping predators, accessing distant food sources, and finding optimal nesting sites—flight comes with trade-offs. Reproductive investment is often lower in flying birds compared to flightless ones; eggs tend to be smaller relative to body size, and clutch sizes are generally modest. Additionally, the complex musculoskeletal and neurological systems required for flight limit evolutionary flexibility in other directions.

Cultural and Symbolic Meanings of Flight

Beyond biology, the question of how can birds fly resonates deeply in human culture and symbolism. Across civilizations, bird flight has represented freedom, transcendence, and spiritual elevation. In ancient Egypt, the soul was depicted as a bird with a human head (the 'ba'), symbolizing the ability to move freely between worlds. In Greek mythology, Icarus attempted to escape captivity using waxen wings—an enduring cautionary tale about ambition and limits.

In many Indigenous traditions, birds serve as messengers between earth and sky, their flight path interpreted as divine signs. Eagles, in particular, are revered in Native American cultures as symbols of courage and connection to the Creator. Similarly, doves represent peace and the Holy Spirit in Christian iconography, their gentle flight evoking purity and grace.

Modern society continues to draw inspiration from avian flight. The Wright brothers studied pigeons extensively before achieving powered human flight in 1903. Today, biomimicry in engineering—such as drone design and wing morphing technologies—often looks to birds for solutions to aerodynamic challenges.

Practical Tips for Observing Bird Flight

For birdwatchers and nature enthusiasts, observing flight patterns can reveal much about species identity, behavior, and health. Here are practical tips to enhance your understanding of how birds fly:

- Learn flight silhouettes: At a distance, you can identify birds by the shape of their wings and body in flight. Hawks have broad, rounded wings; swallows have long, pointed ones; woodpeckers show a flap-and-glide pattern.

- Watch wingbeat frequency: Fast, rapid beats suggest small birds like finches; slow, deep flaps indicate larger species like herons or geese.

- Note flock formations: Geese fly in V-formations for energy conservation; shorebirds may wheel in synchronized clouds, a defense mechanism against predators.

- Use binoculars and field guides: Choose optics with good clarity and magnification (8x or 10x). Pair them with apps or books that include flight illustrations.

- Visit key locations: Coastal cliffs, mountain ridges, and wetlands often concentrate migrating birds. Timing matters—spring and fall migrations offer peak activity.

| Bird Species | Wing Shape | Flight Style | Typical Speed (mph) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peregrine Falcon | Tapered, pointed | Powered dive (stoop) | 240 (dive) |

| Barn Swallow | Long, pointed | Agile, acrobatic | 35 |

| Great Blue Heron | Broad, rectangular | Slow, deep flaps | 20 |

| Anna’s Hummingbird | Short, narrow | Hovering, darting | 30 |

| Canada Goose | Long, broad | V-formation flapping | 40 |

Common Misconceptions About Bird Flight

Several myths persist about how birds fly. One common misconception is that all birds can fly. In reality, around 60 extant species are flightless, having evolved in isolated ecosystems where flight was no longer advantageous. Another myth is that feathers alone enable flight. While essential, feathers work in concert with skeletal structure, musculature, and neurology. Without the right internal framework, even perfect feathers wouldn’t allow flight.

Some believe smaller birds fly faster due to quicker wingbeats. However, speed depends more on wing loading (body mass relative to wing area) and aspect ratio (wing length vs. width). Larger birds like albatrosses and geese often outpace smaller ones in level flight.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Why can't all birds fly? Flightlessness evolves when environmental pressures favor other survival strategies, such as running (ostrich) or diving (penguin), particularly in predator-free islands.

- How do birds navigate during long flights? They use a combination of celestial cues (sun, stars), Earth's magnetic field, landmarks, and even olfactory signals.

- Do birds sleep while flying? Some seabirds, like frigatebirds, have been shown to sleep mid-air using unihemispheric slow-wave sleep—one brain hemisphere rests while the other remains alert.

- Can injured birds regain flight ability? With proper rehabilitation, yes. Wildlife centers often treat broken wings or feather damage, restoring flight after healing.

- How fast can birds fly? Most cruise between 20–50 mph, but the peregrine falcon reaches over 240 mph in a dive, making it the fastest animal on Earth.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4