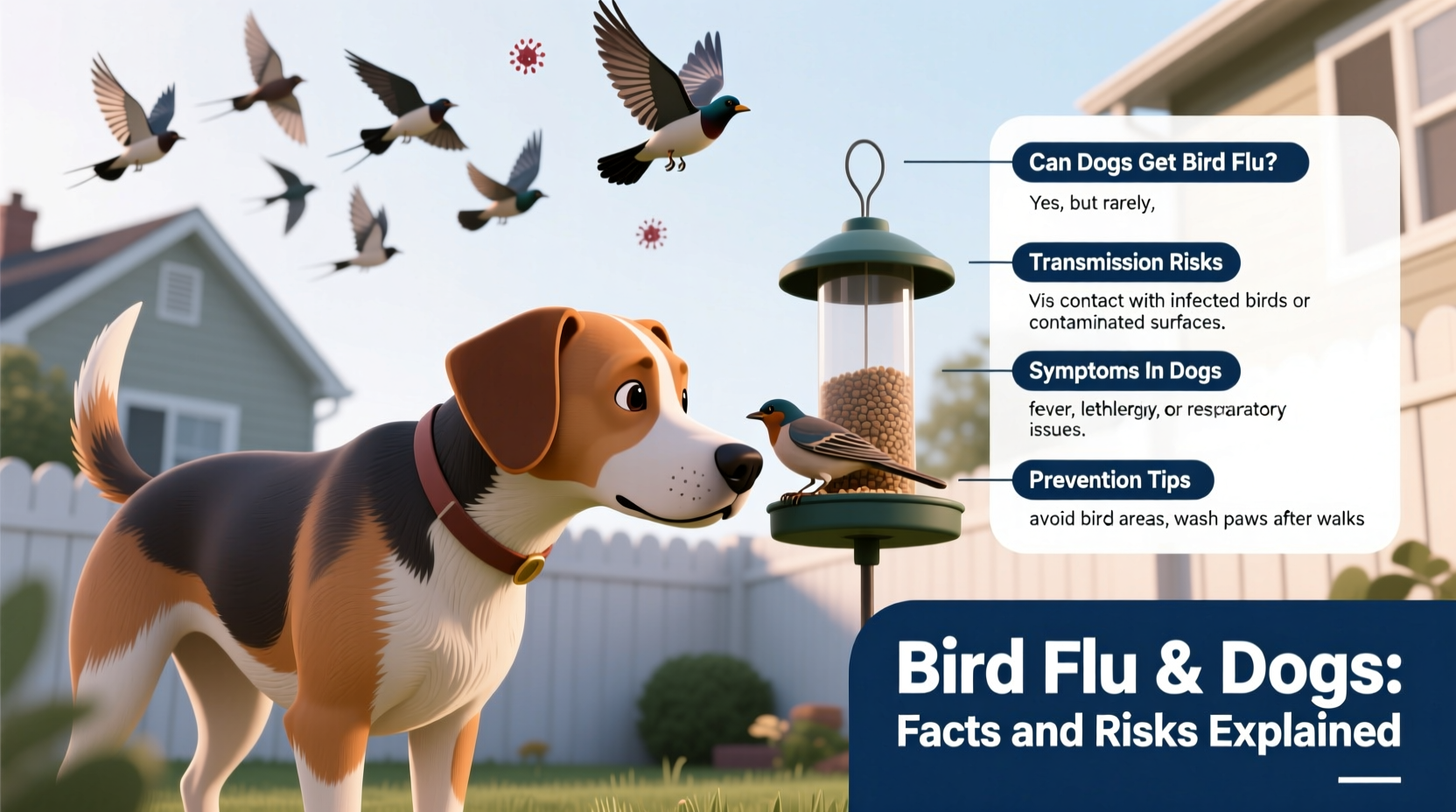

Bird flu, also known as avian influenza, does not typically affect dogs, but under rare circumstances, canines may become infected after close contact with infected birds or contaminated environments. While dogs are not natural hosts for the virus, understanding whether bird flu affects dogs is essential for pet owners, especially those living near areas with reported outbreaks. This article explores the biological realities of avian influenza transmission, evaluates documented cases involving dogs, and offers practical guidance for minimizing risk—ensuring you have accurate, science-based information on how bird flu in dogs occurs, if at all.

Understanding Avian Influenza: What It Is and How It Spreads

Avian influenza (AI) refers to a group of influenza viruses that primarily infect birds, both wild and domesticated. These viruses are classified into subtypes based on two surface proteins: hemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N), such as H5N1 or H7N9. Most strains circulate among waterfowl and shorebirds, which often show no symptoms despite carrying the virus.

The virus spreads through direct contact with infected birds, their droppings, saliva, or contaminated surfaces like feeders, cages, or water sources. Outbreaks commonly occur during migration seasons when large populations of birds congregate in shared habitats. While AI is highly contagious among birds, its ability to cross species barriers is limited—but not impossible.

Human infections are rare but have occurred, usually among individuals with prolonged exposure to infected poultry. Similarly, other mammals—including foxes, seals, and even cats—have tested positive during surveillance efforts following major avian flu events. The question of whether bird flu can spread to dogs has gained attention due to these interspecies transmissions.

Can Dogs Get Bird Flu? Examining Scientific Evidence

While dogs are not considered susceptible hosts for avian influenza, there have been isolated reports suggesting possible infection under specific conditions. A study published in 2014 observed antibodies against H5N1 in stray dogs in Egypt, indicating prior exposure to the virus. However, none of the animals showed clinical signs of illness, raising questions about whether they were truly infected or merely exposed.

In laboratory settings, researchers have successfully infected dogs with high doses of H5N1, demonstrating that the virus can replicate within canine respiratory tissues. Yet, this does not reflect real-world scenarios where exposure levels are significantly lower. Moreover, infected dogs did not transmit the virus efficiently to other dogs, suggesting minimal public health risk.

To date, no confirmed cases of symptomatic bird flu in household pets have been reported in North America or Western Europe. Surveillance programs by organizations such as the CDC and OIE continue monitoring potential spillover events, particularly in regions experiencing widespread poultry outbreaks.

Symptoms to Watch For: Could Your Dog Be Affected?

If a dog were to contract avian influenza, symptoms would likely resemble those of other respiratory infections. Potential signs include:

- Coughing or sneezing

- Nasal discharge

- Lethargy or decreased activity

- Loss of appetite

- Fever

- Difficulty breathing

However, these symptoms are non-specific and more commonly caused by kennel cough, canine influenza (a different virus), or bacterial infections. There is currently no diagnostic test routinely used to detect avian flu in dogs unless there's a known exposure history—such as contact with dead wild birds or infected poultry farms.

Pet owners should avoid jumping to conclusions based on mild respiratory issues. Instead, consult a veterinarian who can assess your dog’s environment, travel history, and potential exposures before recommending testing or treatment.

Risk Factors: When Might Dogs Be Exposed to Bird Flu?

Although the overall risk remains low, certain situations increase the likelihood of exposure:

- Living near affected poultry farms: Areas with confirmed avian flu outbreaks in commercial flocks pose higher environmental contamination risks.

- Allowing dogs to scavenge dead birds: Curious dogs may pick up or chew on carcasses of infected birds, introducing the virus via oral or nasal routes.

- Off-leash activities in wetlands or migratory zones: Regions frequented by migratory waterfowl may harbor the virus in soil or water.

- Urban parks with large bird populations: Though less common, urban ducks or gulls could potentially carry the virus during outbreak periods.

Dogs used in hunting or field trials may face increased exposure due to frequent interaction with wildlife. Owners of sporting breeds should remain vigilant during peak bird migration months (spring and fall) and consider restricting access to ponds or marshy areas where waterfowl gather.

Prevention Tips: Protecting Your Dog from Bird Flu

Given the rarity of infection, routine vaccination or prophylactic measures are not recommended. However, responsible pet ownership includes taking sensible precautions:

- Prevent scavenging behavior: Train your dog to respond reliably to recall commands so you can stop them from approaching dead birds.

- Avoid high-risk areas: During active avian flu outbreaks, check local wildlife agency advisories and avoid walking your dog in quarantined zones.

- Practice good hygiene: Wash your hands after handling birds or visiting farms. Clean your dog’s paws after outdoor excursions in potentially contaminated areas.

- Report sick or dead birds: Contact local animal control or wildlife authorities instead of handling carcasses yourself.

- Stay informed: Monitor updates from trusted sources like the USDA, CDC, or World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH).

Veterinarians play a key role in early detection. If your dog develops unexplained respiratory symptoms and has had recent exposure to wild birds, inform your vet immediately. They may coordinate with state labs for specialized testing if warranted.

Comparative Susceptibility: Dogs vs. Cats and Other Mammals

Interestingly, cats appear more vulnerable to avian influenza than dogs. Multiple studies have shown that domestic cats can become infected by consuming raw meat from infected birds and may even develop severe pneumonia. In contrast, dogs seem to resist infection more effectively, possibly due to differences in receptor distribution in their respiratory tracts.

Other mammals like minks, ferrets, and marine mammals have also shown susceptibility, often linked to dense farming conditions or proximity to infected bird colonies. This highlights that while cross-species transmission is uncommon, it tends to occur in contexts involving intense exposure or compromised immune systems.

| Species | Known Cases of Infection | Severity of Illness | Transmission Risk |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dogs | Antibodies detected; no confirmed illness | Low (asymptomatic) | Very low |

| Cats | Confirmed experimental & natural cases | Moderate to high | Low (limited cat-to-cat) |

| Humans | Rare occupational cases | Variable, sometimes fatal | Very low |

| Minks | Outbreaks in farmed populations | High mortality | Moderate (mink-to-mink) |

Public Health Implications and Monitoring Efforts

While the primary concern with avian flu remains its impact on poultry industries and potential human pandemics, monitoring spillover into companion animals serves as an important early warning system. Dogs, being close human companions, could theoretically act as intermediate hosts—though no evidence supports this currently.

Global surveillance networks track unusual disease patterns in animals. For instance, the One Health initiative integrates data from veterinary, medical, and environmental sectors to detect emerging threats. If future research identifies sustained transmission in dogs or mutations allowing easier adaptation to mammals, public health protocols may need updating.

For now, however, agencies agree that pet dogs pose no significant risk of spreading avian influenza to humans or other animals. The focus remains on controlling outbreaks in bird populations through biosecurity measures, culling infected flocks, and developing vaccines for poultry.

Common Misconceptions About Bird Flu and Pets

Several myths persist regarding bird flu and its effects on household pets:

- Misconception: All birds carry bird flu.

Fact: Most wild birds do not have the virus; only certain species in active outbreak zones are likely carriers. - Misconception: Letting your dog chase ducks spreads bird flu easily.

Fact: Brief interactions pose negligible risk; transmission requires significant viral load exposure. - Misconception: There’s a vaccine for dogs against bird flu.

Fact: No such vaccine exists, nor is it needed given current evidence. - Misconception: Canine influenza is the same as bird flu.

Fact: Canine flu (H3N8, H3N2) is a separate virus adapted to dogs and unrelated to avian strains.

Staying informed through credible scientific sources helps dispel fear-driven misinformation and promotes rational decision-making.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- Can my dog get bird flu from eating a dead bird?

It’s theoretically possible but extremely unlikely. No documented cases exist of dogs becoming ill from scavenging infected birds. - Should I worry about bird flu if I have a backyard flock and a dog?

If your poultry is healthy and vaccinated, risk is minimal. Practice strict biosecurity: keep dogs out of coops and clean footwear before entry. - Is there a test for bird flu in dogs?

Specialized PCR tests exist but are only used in research or outbreak investigations, not routine veterinary care. - Can dogs spread bird flu to people?

No evidence suggests dogs can transmit avian influenza to humans. Direct bird-to-human transmission is far more plausible. - What should I do if my dog shows flu-like symptoms after contacting wild birds?

Contact your veterinarian, provide full exposure history, and isolate your pet until evaluated.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4