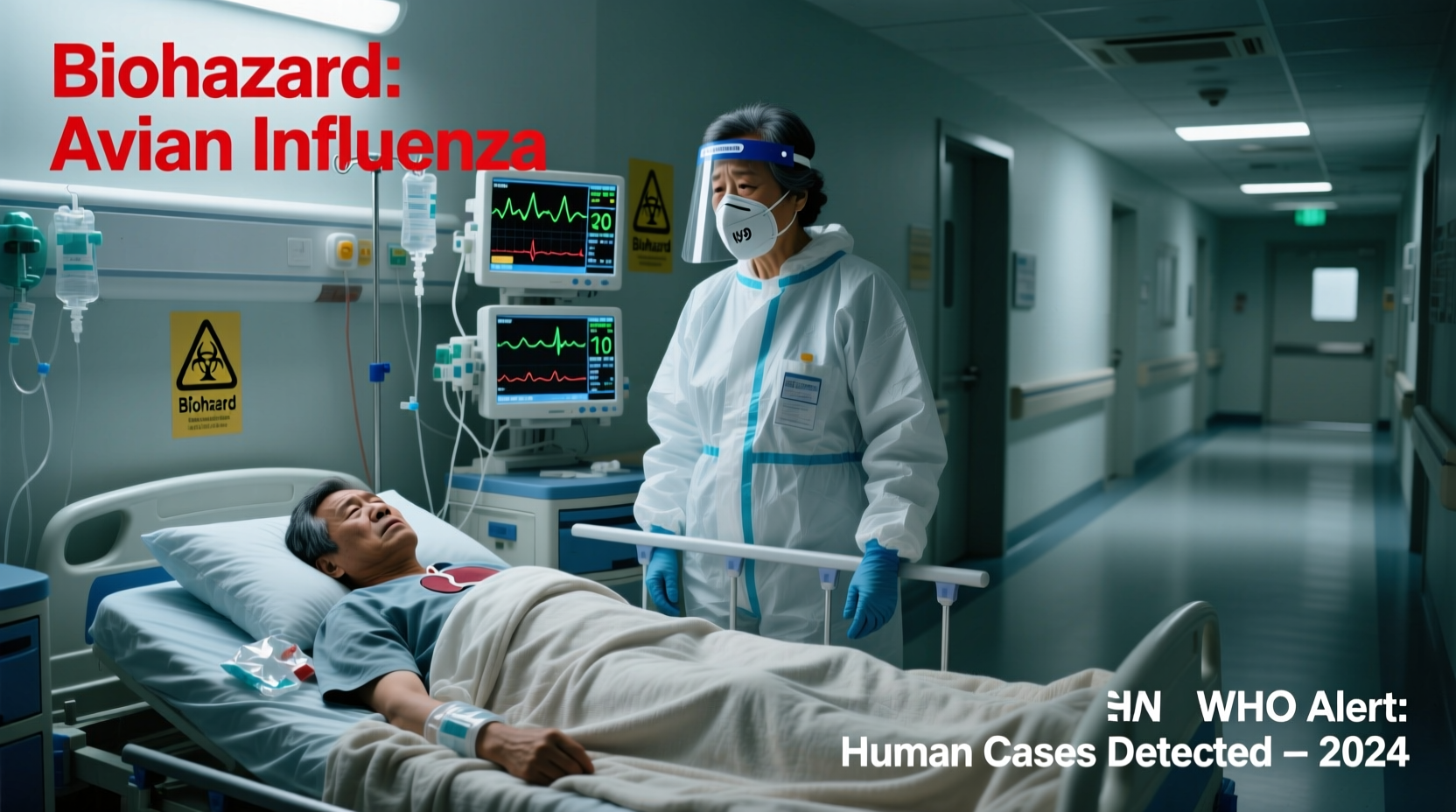

Yes, bird flu has jumped to humans in rare but documented cases, primarily through direct contact with infected poultry or contaminated environments. While human-to-human transmission remains extremely limited, the H5N1 and H7N9 strains of avian influenza have caused severe illness and fatalities in people exposed to sick birds. These zoonotic spillover events underscore the importance of monitoring outbreaks in bird populations, especially among backyard flocks and commercial poultry farms. The question 'has bird flu jumped to humans' is increasingly relevant as global health agencies track mutations that could enhance transmissibility between people.

Understanding Avian Influenza: Origins and Strains

Bird flu, or avian influenza, refers to a group of influenza viruses that primarily infect birds. Wild aquatic birds, such as ducks and geese, are natural reservoirs for these viruses, often carrying them without showing symptoms. However, when the virus spreads to domesticated birds like chickens and turkeys, it can cause high mortality rates and prompt mass culling to prevent further spread.

The most concerning subtypes for public health are H5N1, H7N9, and more recently, H5N8 and H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4b. Since its emergence in Asia in the late 1990s, H5N1 has been responsible for numerous animal outbreaks and over 900 confirmed human cases across 23 countries, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). Fatality rates in humans have exceeded 50% in some strains, though actual infection numbers may be underreported due to limited surveillance in rural areas.

Avian flu viruses are classified by surface proteins: hemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N). There are 18 known H subtypes and 11 N subtypes, creating various combinations. Most do not easily infect humans, but certain mutations—particularly those affecting the HA protein’s ability to bind to human respiratory cells—can increase pandemic risk.

How Has Bird Flu Jumped to Humans? Transmission Pathways

The primary route by which bird flu jumps to humans is through close contact with infected birds or their droppings, secretions, or contaminated surfaces. This typically occurs in agricultural settings, live bird markets, or during slaughter and preparation of poultry. Inhalation of aerosolized particles or touching contaminated surfaces and then the face can lead to infection.

There have been no sustained human-to-human transmissions of H5N1 or H7N9, meaning the virus does not currently spread efficiently from person to person. However, isolated cases suggest limited transmission among family members living in close quarters with prolonged exposure. Scientists remain vigilant about potential genetic reassortment—when avian and human flu viruses mix inside a host (such as pigs)—which could produce a novel strain capable of widespread human transmission.

In 2024, an outbreak of H5N1 in dairy cattle in the United States raised new concerns about cross-species transmission. Several farmworkers tested positive after exposure to infected cows, marking the first known cases linked to mammalian livestock rather than birds directly. This development signals a possible expansion of the virus’s host range and highlights the need for enhanced biosecurity on farms.

Confirmed Cases of Human Infection: Timeline and Geography

The first known case of human infection with H5N1 occurred in Hong Kong in 1997, when six people were infected and two died. After disappearing for several years, the virus re-emerged in 2003 in Southeast Asia, triggering a wave of outbreaks across Asia, Africa, and parts of Europe.

| Year | Location | Strain | Human Cases | Fatalities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1997 | Hong Kong | H5N1 | 6 | 2 |

| 2003–2006 | Multiple countries | H5N1 | 258 | 153 |

| 2013 | China | H7N9 | 1,568 | 616 |

| 2022–2024 | UK, USA, Canada, Europe | H5N1 | Over 50 | At least 12 |

| 2024 | USA (dairy workers) | H5N1 | 9+ (preliminary) | 0 |

Notably, in April 2024, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) confirmed multiple human infections tied to an ongoing H5N1 outbreak in dairy cattle. Affected individuals reported conjunctivitis and mild respiratory symptoms, suggesting possible ocular entry routes. These cases represent a shift in exposure dynamics, indicating that indirect contact via intermediate hosts may now play a role in zoonotic transmission.

Symptoms and Diagnosis in Humans

When bird flu jumps to humans, symptoms can range from mild to life-threatening. Early signs resemble seasonal flu: fever, cough, sore throat, muscle aches, and fatigue. However, progression can be rapid, leading to pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), multi-organ failure, and death.

H7N9 infections tend to cause more severe lower respiratory tract disease, while recent H5N1 cases in the U.S. have presented with eye infections (conjunctivitis), likely due to exposure to nasal secretions from infected animals. Prompt diagnosis is crucial. Testing involves reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assays using respiratory samples or ocular swabs.

Because early symptoms overlap with other illnesses, clinicians must consider travel history, occupational exposure, and contact with sick birds or livestock when evaluating suspected cases. Rapid reporting enables timely antiviral treatment and containment measures.

Prevention and Public Health Measures

Given that bird flu has jumped to humans in specific circumstances, preventive strategies focus on reducing exposure at the animal-human interface. Key recommendations include:

- Avoiding contact with sick or dead birds, especially in regions experiencing outbreaks.

- Using personal protective equipment (PPE) when handling poultry or working on farms.

- Practicing strict hand hygiene after any interaction with birds or animals.

- Cooking poultry and eggs thoroughly (internal temperature ≥165°F / 74°C) to destroy the virus.

- Reporting unusual bird deaths to local wildlife or agricultural authorities.

Vaccination of poultry is used in some countries to control spread, though it doesn’t eliminate the virus entirely. For humans, there is no widely available commercial vaccine against H5N1 or H7N9, but candidate vaccines are stockpiled by governments for emergency use during pandemics.

The CDC and WHO recommend antiviral drugs like oseltamivir (Tamiflu) for early treatment and post-exposure prophylaxis. These medications work best when administered within 48 hours of symptom onset.

Role of Surveillance and Global Monitoring

Ongoing surveillance is essential to detect when bird flu jumps to humans and assess pandemic potential. Programs like the Global Influenza Surveillance and Response System (GISRS) monitor viral evolution in both animal and human populations.

In the U.S., the USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) tracks outbreaks in birds and mammals, while the CDC monitors human cases. International collaboration through organizations like the World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH) ensures data sharing and coordinated responses.

Genomic sequencing plays a critical role in identifying mutations associated with increased transmissibility or resistance to antivirals. For example, changes in the PB2 gene (E627K mutation) allow avian viruses to replicate better at human body temperatures, raising concern for adaptation.

Misconceptions About Bird Flu and Human Risk

Despite growing awareness, several misconceptions persist about whether bird flu has jumped to humans and how dangerous it is:

- Misconception: Eating properly cooked poultry spreads bird flu.

Fact: No confirmed cases have resulted from consuming well-cooked meat or eggs. - Misconception: The virus spreads easily between people.

Fact: Sustained human-to-human transmission has not occurred; most cases involve direct animal contact. - Misconception: Only wild birds carry the virus.

Fact: Domestic poultry and now even dairy cattle can harbor and transmit H5N1. - Misconception: Bird flu is no longer a threat because past outbreaks faded.

Fact: The virus continues to circulate globally and evolve, posing an ongoing risk.

What Should Travelers and Bird Enthusiasts Know?

For birdwatchers, researchers, and travelers visiting areas with active avian flu outbreaks, precautions are vital. Avoid feeding wild birds in urban parks if local advisories warn of infections. Do not approach or handle sick or dead birds. Use binoculars instead of getting too close during observation.

If you're traveling to regions with known H5N1 activity—such as parts of East Asia, the Middle East, or Eastern Europe—check travel health notices from the CDC or WHO before departure. Carry disinfectant wipes and wear gloves if engaging in fieldwork involving birds.

Backyard poultry owners should isolate their flocks from wild birds, clean coops regularly, and report any sudden bird deaths to veterinary services. Some states offer free testing for avian influenza in suspect cases.

Future Outlook and Pandemic Preparedness

While bird flu has jumped to humans only sporadically so far, the increasing frequency of spillover events—including recent infections in cattle and minks—suggests the virus is adapting to new hosts. This raises the likelihood of future mutations that could enable efficient human transmission.

Public health experts emphasize the need for robust pandemic preparedness: strengthening surveillance systems, accelerating vaccine development platforms (like mRNA-based flu vaccines), and improving coordination between human, animal, and environmental health sectors (One Health approach).

Individuals can contribute by staying informed through reliable sources like the CDC, WHO, and national health departments. Awareness of local outbreaks and adherence to safety guidelines reduces personal risk and supports broader containment efforts.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Has bird flu jumped to humans? Yes, in rare cases, primarily through direct contact with infected birds or contaminated environments.

- Can bird flu spread between humans? Not sustainably; limited person-to-person transmission has occurred but hasn't led to community spread.

- Is it safe to eat chicken and eggs? Yes, if properly cooked to an internal temperature of 165°F (74°C).

- Are there vaccines for bird flu in humans? Not commercially available, but experimental vaccines exist for emergency stockpiling.

- What should I do if I find a dead bird? Do not touch it; report it to your local wildlife agency or health department.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4