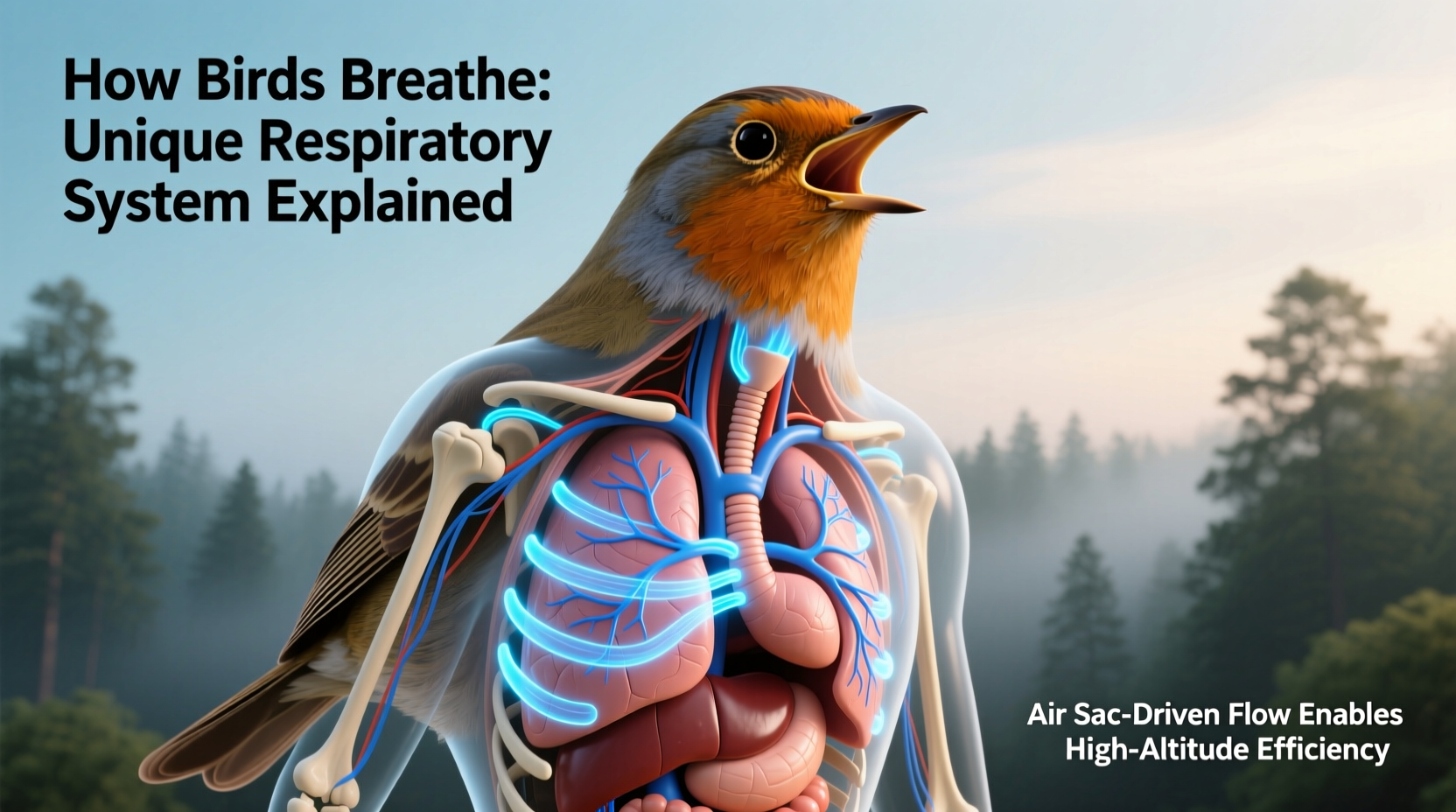

Birds can breathe efficiently due to their unique respiratory system, which allows for a continuous flow of oxygen through their lungsâunlike mammals, birds have rigid lungs connected to air sacs that distribute air throughout their body. This advanced design enables how birds breathe during high-altitude flight, supporting sustained aerobic activity even in low-oxygen environments. The one-way airflow system ensures fresh air moves in a constant direction, maximizing gas exchange efficiency and making avian respiration far more effective than in humans.

Anatomy of the Avian Respiratory System

The secret behind how birds breathe so effectively lies in their specialized anatomy. Unlike mammals, whose lungs expand and contract to pull air in and out, birds possess a network of fixed-volume lungs and nine thin-walled air sacs distributed throughout their torso and even extending into some bonesâa feature known as pneumatization.

Air sacs serve as bellows, moving air unidirectionally through the lungs. When a bird inhales, air doesnât immediately enter the lungs. Instead, it flows first into posterior air sacs. On exhalation, this air is pushed from the posterior sacs into the lungs, where gas exchange occurs. A second inhalation moves the now-oxygen-depleted air from the lungs into anterior air sacs, and a final exhalation expels it. This two-cycle process ensures that oxygen-rich air passes through the lungs during both inhalation and exhalationâan evolutionary adaptation critical for meeting the high metabolic demands of flight.

This mechanism answers the fundamental question: how can birds breathe continuously during strenuous activities like migration or hovering? Their respiratory system delivers nearly twice as much oxygen per unit of body mass compared to mammals, enabling feats such as bar-headed geese flying over Mount Everest, where oxygen levels are less than one-third of those at sea level.

Key Components: Lungs, Air Sacs, and Parabronchi

Bird lungs are small, dense, and firmly attached to the ribcage, preventing expansion. Gas exchange takes place not in alveoli (as in mammals) but within tiny tubules called parabronchi. These structures are lined with capillaries and allow cross-current exchange of gases. In this setup, air flows perpendicular to blood flow, creating a highly efficient gradient that maximizes oxygen diffusion into the bloodstream.

The nine air sacs include:

- Cervical air sacs (in the neck)

- Clavicular air sac (single, near the shoulders)

- Anterior thoracic air sacs

- Posterior thoracic air sacs

- Abdominal air sacs

These sacs extend into cavities within bonesâespecially the humerus, femur, and vertebraeâlightening the skeleton without compromising strength. This integration between respiration and skeletal structure is another reason why birds can breathe efficiently while maintaining the lightweight frame necessary for flight.

Why Don't Birds Suffocate at High Altitudes?

One of the most fascinating aspects of avian respiration is how birds breathe under extreme conditions. Species like the bar-headed goose (Anser indicus) migrate over the Himalayas, reaching altitudes above 29,000 feet. At these elevations, atmospheric pressure drops dramatically, reducing available oxygen.

Several physiological adaptations make this possible:

- Hemoglobin with higher oxygen affinity: Bird hemoglobin binds oxygen more readily than human hemoglobin, capturing scarce molecules even when partial pressure is low.

- Increased capillary density in muscles: More oxygen delivery pathways mean better tissue utilization.

- Efficient ventilation-perfusion matching: Blood flow and airflow are precisely coordinated in the parabronchi.

- Enhanced mitochondrial density: Muscle cells contain more energy-producing organelles, improving aerobic capacity.

Researchers studying how birds breathe at high altitudes have found that some species also reduce metabolic rate mid-flight and use favorable wind currents to minimize exertion. These combined traits explain how certain birds survive what would be lethal hypoxia for most mammals.

Differences Between Bird and Mammal Respiration

A common misconception is whether birds are mammals. They are notâbirds belong to the class Aves, separate from Mammalia. One major distinction lies in how they breathe. Mammals rely on tidal breathing: air moves in and out of the same pathway, resulting in dead space where stale air mixes with fresh intake. Birds avoid this inefficiency entirely.

| Feature | Birds | Mammals |

|---|---|---|

| Lung Structure | Rigid, fixed-volume; parabronchi-based | Elastic, alveolar |

| Airflow Pattern | Unidirectional (one-way) | Tidal (in-and-out) |

| Air Sacs Present? | Yes (9 total) | No |

| Bone Pneumatization | Common (air-filled bones) | Absent |

| Oxygen Efficiency | Very high (continuous flow) | Moderate (mixing in dead space) |

This structural divergence underscores why understanding how birds breathe differently from humans is essential for both biological research and veterinary medicine. It also highlights evolutionary solutions to environmental challenges.

Respiratory Health in Birds: Signs of Trouble

Because their respiratory system is so complex, birds are vulnerable to infections and environmental hazards. Common signs that a bird may be struggling to breathe include:

- Rapid or labored breathing (dyspnea)

- Open-mouth breathing (especially in non-passerines like pigeons or raptors)

- Wheezing, clicking, or sneezing sounds

- Fluffed feathers and lethargy

- Nasal discharge

In captivity, poor ventilation, dust, mold, or exposure to toxic fumes (e.g., Teflon off-gassing) can impair how birds breathe. Pet owners must ensure clean, well-ventilated enclosures and avoid aerosol sprays near birds. Wild birds face threats from pollutants, smoke, and diseases like avian influenza, which can damage lung tissue.

Veterinarians often use radiographs or endoscopy to assess internal air sac health. Early diagnosis is crucial because respiratory distress progresses quickly in birds due to their high metabolic rate.

Observing Breathing Patterns in Wild Birds: Tips for Birdwatchers

Understanding how birds breathe enhances field observation. While you wonât see internal processes, external cues offer insight:

- Watch for subtle movements: Air sac inflation may cause slight bulging behind the sternum or along the flanks.

- Note behavioral changes post-flight: After intense activity, some birds gape (open their beaks), panting to cool down and increase airflowâthis is normal thermoregulation, not necessarily distress. \li>Listen carefully: Some species produce soft hissing or cooing sounds during respiration, especially doves and pigeons.

- Use binoculars or spotting scopes: Observe breathing rhythms during rest periods to establish baseline behavior for comparison.

Birders should distinguish between normal panting (after flight or in heat) and abnormal breathing (wheezing, tail bobbing with each breath). Tail bobbing, in particular, indicates effort and may signal illness.

Evolutionary Origins of the Avian Respiratory System

The question of how birds evolved to breathe so efficiently traces back to their dinosaur ancestors. Fossil evidence shows that theropod dinosaursârelatives of modern birdsâhad hollow bones and likely possessed air sac systems similar to todayâs avians. This suggests that the foundations of unidirectional airflow predate flight itself.

Paleontologists believe that early air sacs evolved for thermoregulation or weight reduction in large terrestrial predators. Over millions of years, these structures became integrated with pulmonary function, eventually supporting powered flight. The transition from bipedal runners to flying birds involved numerous incremental changes, with respiration playing a pivotal role.

Studying extinct species like Archaeopteryx and Velociraptor helps scientists reconstruct how breathing mechanisms evolved. CT scans of fossilized skulls and vertebrae reveal channels consistent with air sac extensions, reinforcing the link between dinosaurs and modern avian physiology.

Myths and Misconceptions About Bird Breathing

Despite scientific clarity, several myths persist about how birds breathe:

- Myth: Birds breathe like humans, just faster.

Fact: Their entire system operates on a different principleâunidirectional flow vs. tidal breathing. - Myth: Small birds canât fly long distances because theyâd run out of breath.

Fact: Hummingbirds migrate hundreds of miles using fat stores and efficient oxygen use. - Myth: If a bird opens its mouth, itâs choking.

Fact: Many birds gape to regulate temperature; only paired with other symptoms does it indicate trouble.

Correcting these misunderstandings improves public awareness and conservation efforts. Educating communities about how birds breathe and survive extreme conditions fosters appreciation for their biological uniqueness.

FAQs: Common Questions About Bird Respiration

- Do birds breathe through their mouths?

- Birds primarily breathe through their nostrils (nares), but they can open their beaks to increase airflow during panting or heat dissipation. Mouth breathing isnât their default mode but serves specific purposes.

- Can birds hold their breath underwater?

- Some diving birds, like penguins and cormorants, can slow metabolism and store oxygen in muscles (via myoglobin) to stay submerged for several minutes, though they donât truly âholdâ their breath like marine mammals.

- How fast do birds breathe?

- Resting rates vary by size: a hummingbird may take 250 breaths per minute, while an eagle breathes around 10â30 times per minute. During flight, rates increase significantly.

- Do all birds have the same number of air sacs?

- Most birds have nine air sacs, but minor variations exist among species. Flightless birds like ostriches retain the basic structure, though with reduced volume relative to flyers.

- Why donât birds get dizzy when flying upside down?

- Their respiratory and circulatory systems maintain steady oxygen supply regardless of orientation. Additionally, their inner ear balance organs are adapted for aerial maneuvering.

In summary, the answer to how can birds breathe reveals a marvel of natural engineering. From microscopic parabronchi to expansive air sac networks, every element supports survival in dynamic environments. Whether observing backyard sparrows or migratory shorebirds, appreciating their respiratory prowess deepens our understanding of avian life.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4