Birds breathe using a highly efficient respiratory system that is fundamentally different from mammals, allowing them to meet the high oxygen demands of flight. Unlike humans, who rely on a simple in-and-out airflow through lungs, birds have a unique one-way airflow system powered by air sacs distributed throughout their bodies. This specialized anatomy enables continuous oxygen absorption during both inhalation and exhalation—a key adaptation for sustained flight and high-altitude performance. Understanding how do birds breath reveals not only their remarkable biology but also explains why they can thrive in environments where oxygen is scarce, such as the upper atmosphere.

Anatomy of the Avian Respiratory System

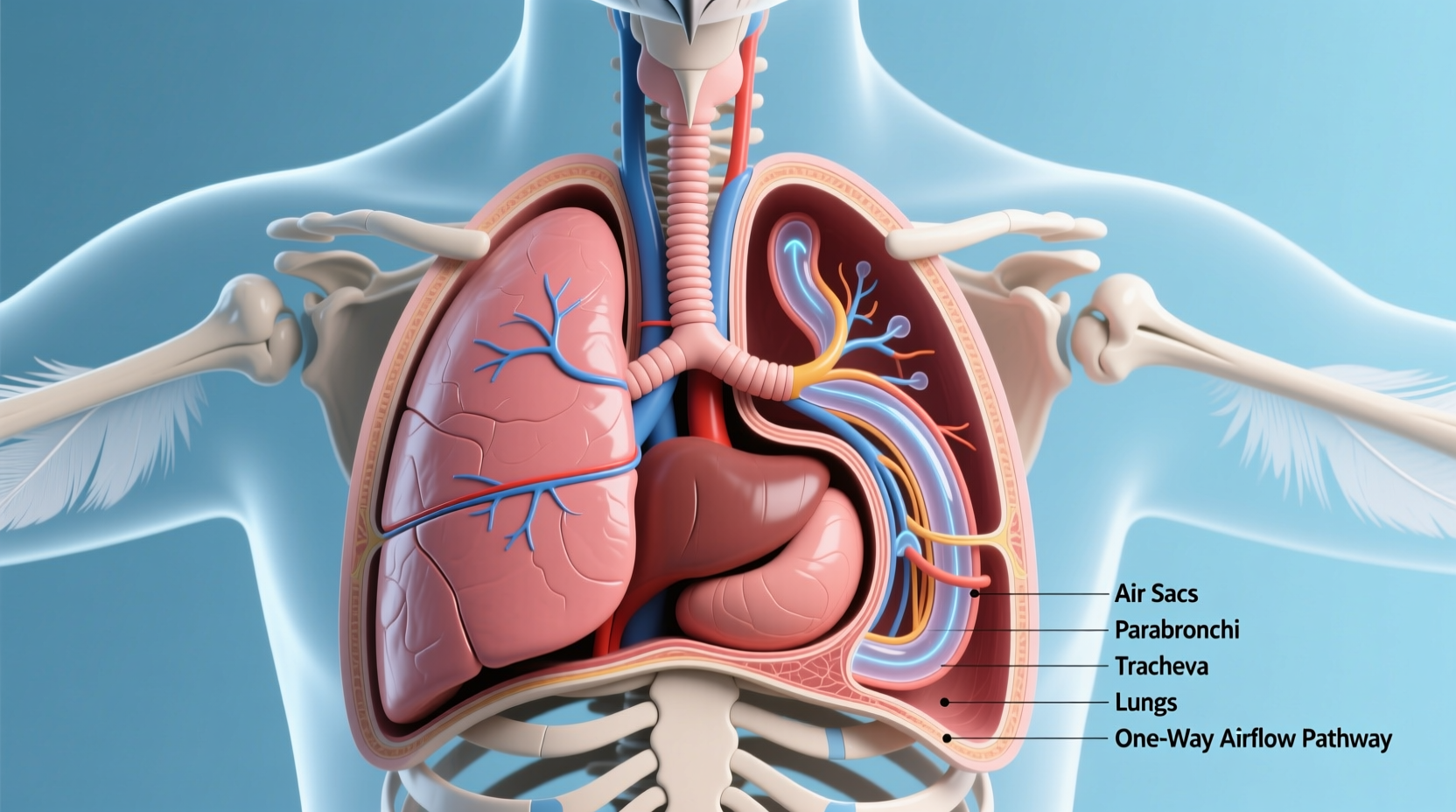

The avian respiratory system consists of several interconnected components: nostrils (nares), trachea, syrinx, lungs, and a network of air sacs. While these structures may sound similar to mammalian anatomy, their function and arrangement are uniquely adapted to support birds’ energetic lifestyles.

Air enters through the nares located at the base of the beak. From there, it travels down the trachea, which is reinforced with cartilaginous rings to prevent collapse during rapid breathing. At the bottom of the trachea lies the syrinx—the vocal organ of birds—before air moves into the primary bronchi leading to the lungs and air sacs.

Unlike mammalian lungs, which expand and contract during breathing, bird lungs are rigid and fixed in place. Instead of relying on lung expansion, birds use nine thin-walled air sacs—four paired and one unpaired—that act as bellows to move air unidirectionally through the lungs. These include the cervical, clavicular, anterior thoracic, posterior thoracic, and abdominal air sacs.

One-Way Airflow: The Key to Efficiency

One of the most distinctive features of how do birds breath is the unidirectional flow of air through their lungs. In mammals, air flows in and out of the same pathways, resulting in a mixing of fresh and stale air within the alveoli. This creates a lower efficiency in gas exchange.

In contrast, birds maintain a constant forward movement of air through their parabronchi—the functional units of avian lungs. During inhalation, air first moves into the posterior air sacs. On exhalation, this air is pushed into the lungs, where gas exchange occurs. A second inhalation moves the now-oxygen-depleted air into the anterior air sacs, and a final exhalation expels it from the body.

This four-stage cycle ensures that oxygen-rich air passes continuously through the lungs, maximizing oxygen uptake. It’s an elegant solution to the challenge of supplying enough oxygen during activities like long-distance migration or hovering flight, such as seen in hummingbirds.

Efficiency and Adaptations for Flight

The efficiency of avian respiration directly supports the extreme metabolic demands of flight. Flying requires up to 15 times more energy per unit time than resting, necessitating a correspondingly high rate of oxygen delivery to muscles.

Birds achieve this through several physiological adaptations:

- Dense capillary networks: Avian lungs contain a dense mesh of blood capillaries surrounding the parabronchi, enhancing the surface area for gas exchange.

- Cross-current exchange system: Blood flows perpendicular to the direction of air movement in the lungs, creating a more efficient gradient for oxygen diffusion compared to the tidal flow in mammals.

- High ventilation rates: Birds can breathe rapidly without losing control over blood pH, thanks to precise regulation of carbon dioxide levels.

- Hollow bones connected to air sacs: Some air sacs extend into the bones (pneumatized bones), reducing overall body weight and improving respiratory efficiency.

These adaptations allow birds like bar-headed geese to fly over Mount Everest, where oxygen levels are less than one-third of those at sea level. Their hemoglobin has a higher affinity for oxygen, and their lungs extract oxygen more efficiently than any mammal, including elite human athletes.

Comparative Physiology: Birds vs. Mammals

A common misconception is whether birds are mammals. They are not. Birds belong to the class Aves, while mammals are in the class Mammalia. One of the clearest distinctions lies in their respiratory systems.

| Feature | Birds | Mammals |

|---|---|---|

| Lung Structure | Rigid, fixed lungs with parabronchi | Elastic, expanding alveolar lungs |

| Airflow Pattern | Unidirectional (one-way) | Tidal (in-and-out) |

| Air Sacs | Present (9 total) | Absent |

| Gas Exchange Timing | Dual-phase (during inhalation and exhalation) | Primarily during inhalation |

| Ventilation Mechanism | Sternal pumping via air sacs | Diaphragm and intercostal muscles |

This comparison highlights why asking 'how do birds breath' leads to a deeper understanding of evolutionary specialization. While mammals evolved for flexibility and endurance across diverse environments, birds optimized for aerial performance and metabolic intensity.

Respiratory Challenges and Vulnerabilities

Despite its advantages, the avian respiratory system is vulnerable to certain threats. Because air sacs extend into body cavities and even bones, infections can spread quickly. Birds lack a diaphragm and cannot cough effectively, making them susceptible to respiratory diseases such as Aspergillosis (a fungal infection) or Avian Influenza.

Pollutants and airborne toxins pose significant risks. Due to their high ventilation rates and sensitive lung tissues, birds often serve as bioindicators of environmental health. For example, canaries were historically used in coal mines to detect dangerous gases because they showed signs of distress before humans.

Urban air pollution, pesticide exposure, and climate change all impact avian respiration. Warmer temperatures increase metabolic rates, raising oxygen demand, while pollutants damage delicate respiratory tissues. Conservation efforts must consider these invisible stressors when protecting bird populations.

Observing Bird Breathing: Tips for Birdwatchers

For amateur ornithologists and nature enthusiasts, observing breathing patterns in birds can provide insights into their behavior and health. Here are practical tips:

- Watch for subtle movements: Since birds don’t have visible chest expansions like mammals, look for slight pulsations near the sternum or flanks, especially in perched birds.

- Note breathing rate during activity: After flight, birds may pant slightly, similar to dogs, to cool down and replenish oxygen. Rapid breathing post-exertion is normal unless prolonged.

- Listen for abnormal sounds: Wheezing, clicking, or labored breathing may indicate illness. If observed in wild birds, report unusual symptoms to local wildlife authorities.

- Use binoculars or spotting scopes: Observe from a distance to avoid stressing the animal. Stress itself can alter breathing patterns.

- Learn species-specific norms: Smaller birds like finches have faster metabolic rates and thus higher resting respiration rates (up to 100 breaths per minute), while larger birds like eagles breathe more slowly.

Understanding how do birds breath enhances your observational skills and deepens appreciation for their physiology. When you see a hawk circling at great height or a warbler flitting through foliage, remember the intricate internal machinery enabling those feats.

Cultural and Symbolic Interpretations of Bird Breathing

Beyond biology, the act of breathing in birds carries symbolic weight across cultures. In many traditions, birds represent the soul, spirit, or divine messengers—partly due to their ability to ascend toward the heavens.

In ancient Egyptian mythology, the bau (plural of ba) was depicted as a bird with a human head, symbolizing the soul's mobility between worlds. The breath of life was associated with flight and spiritual elevation.

In Native American beliefs, eagles carry prayers to the Creator on each breath, linking respiration with communication and transcendence. Similarly, in Hindu philosophy, the Sanskrit word 'prana' refers to life force or vital breath, often symbolized by birds in flight.

Even modern idioms reflect this connection: 'free as a bird' implies unrestricted existence, possibly echoing the effortless breathing and flying that seem so natural to avian creatures.

Common Misconceptions About Bird Respiration

Several myths persist about how birds breathe:

- Myth: Birds breathe like humans. False. Their one-way airflow system is fundamentally different and far more efficient.

- Myth: Birds can hold their breath underwater. Most cannot. Diving birds like cormorants rely on stored oxygen in blood and muscles, not lung capacity alone.

- Myth: Feathers help with breathing. No. Feathers insulate and aid flight, but play no role in respiration.

- Myth: Birds breathe through their mouths. Rarely. They primarily use nostrils, though some open-mouth breathing occurs during thermoregulation.

Dispelling these misconceptions helps foster accurate public understanding of avian biology.

Scientific Research and Future Directions

Ongoing research continues to uncover new aspects of avian respiration. Scientists study bird lungs to inspire advancements in mechanical ventilation systems and aerospace engineering. The cross-current exchange model has influenced designs for more efficient industrial gas filters and oxygenators.

Additionally, tracking devices and respirometry studies allow researchers to measure real-time oxygen consumption in migrating species. These data help predict how climate change might affect bird distribution and survival.

Genetic studies are exploring how developmental genes guide the formation of air sacs and lung structure. Such knowledge could inform regenerative medicine, particularly in treating human lung diseases.

Frequently Asked Questions

How do birds breathe while flying?

Birds maintain continuous oxygen flow through their one-way respiratory system. Air sacs pump air steadily through rigid lungs, ensuring oxygen delivery even during rapid wingbeats.

Do birds have lungs and a diaphragm?

Yes, birds have lungs, but they lack a diaphragm. Instead, they use chest and abdominal muscles to expand and contract air sacs for ventilation.

Can birds breathe underwater?

No, birds cannot breathe underwater. Diving species store oxygen in their blood and muscles and must return to the surface to exhale and inhale.

Why don't birds get dizzy at high altitudes?

Their efficient lungs and oxygen-carrying hemoglobin allow them to maintain brain function even in low-oxygen environments, preventing hypoxia-related dizziness.

How fast do birds breathe?

Respiration rates vary by size: small birds may take 60–100 breaths per minute at rest, while large birds like swans breathe as slowly as 10–15 times per minute.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4