Birds fertilize eggs through internal fertilization, a biological process in which the male bird transfers sperm to the female's cloaca during mating, allowing the egg to be fertilized before the shell forms. This natural reproductive mechanism—often referred to as avian internal fertilization—ensures that the genetic material from both parents combines within the female’s reproductive tract. Unlike mammals, birds do not give birth to live young; instead, they lay eggs that have been fertilized internally and then incubated outside the body. Understanding how do birds fertilize eggs reveals key insights into avian biology, breeding behaviors, and nesting patterns essential for both scientific research and birdwatching enthusiasts.

Avian Reproductive Anatomy: The Foundation of Egg Fertilization

To fully grasp how birds fertilize eggs, one must first understand their unique reproductive anatomy. Both male and female birds possess a cloaca—a single opening used for excretion and reproduction, often called the 'vent.' During mating, the male and female press their cloacae together in what is known as a 'cloacal kiss,' facilitating the transfer of sperm from the male to the female. This brief contact is sufficient for successful fertilization.

Male birds typically lack external genitalia found in many other vertebrates. Instead, most species rely on the eversion of the inner walls of the cloaca to form a temporary intromittent organ, especially in waterfowl like ducks and geese. In contrast, passerines (perching birds such as sparrows and robins) achieve fertilization through precise alignment during the cloacal kiss without permanent structures.

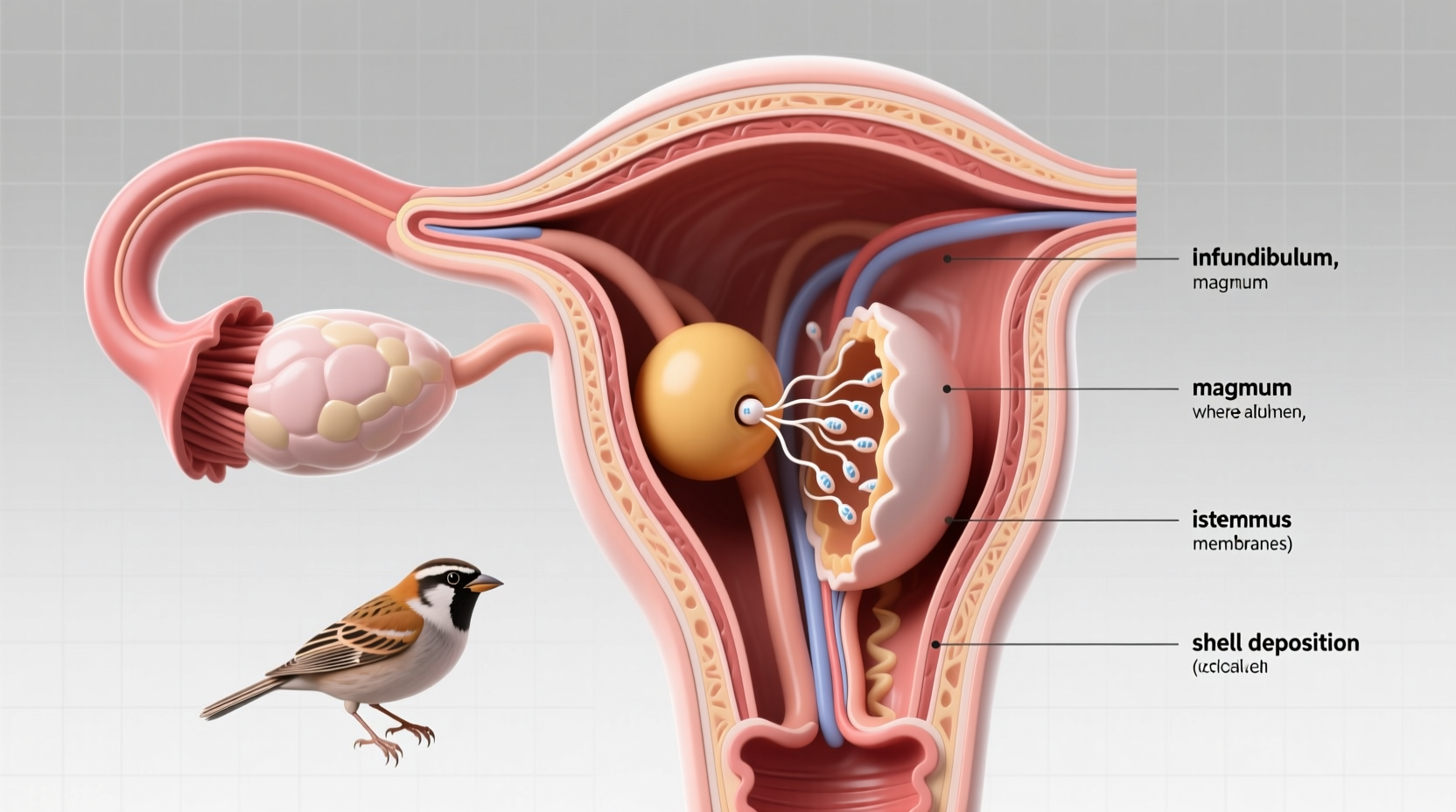

The female bird’s ovary contains hundreds or even thousands of ova (egg cells), though only a few will mature. Once an ovum is released into the oviduct, it travels through several distinct regions where albumen (egg white), membranes, and finally the calcium carbonate shell are added. Crucially, if sperm are present in the oviduct—deposited during recent mating—the ovum becomes fertilized within the infundibulum, the uppermost section of the oviduct, within 15 to 30 minutes after ovulation.

The Process of Internal Fertilization in Birds: Step by Step

The complete journey of how do birds fertilize eggs involves a well-orchestrated sequence of physiological events:

- Ovulation: A mature yolk-laden ovum is released from the ovary into the oviduct.

- Fertilization: If viable sperm are present in the infundibulum, fertilization occurs here almost immediately after ovulation.

- Egg Formation: As the fertilized ovum moves down the oviduct, layers are sequentially added: magnum (albumen), isthmus (shell membranes), uterus (shell formation and pigmentation), and finally the vagina.

- Laying: After approximately 24 hours, the fully formed egg is laid via the cloaca.

Sperm can remain viable inside the female’s sperm storage tubules for days or even weeks, depending on the species. For example, chickens can store sperm for up to two weeks, enabling multiple eggs to be fertilized from a single mating event. This adaptation increases reproductive efficiency, particularly important for wild birds with limited mating opportunities.

Breeding Seasons and Mating Behaviors Influencing Fertilization Success

Understanding when birds mate provides further context for how do birds fertilize eggs successfully in nature. Most bird species are seasonal breeders, timing their reproductive cycles with environmental cues such as day length (photoperiod), temperature, and food availability. These factors trigger hormonal changes that stimulate gonadal development and sexual behavior.

In temperate zones, spring is the peak breeding season. Species like American robins (Turdus migratorius) begin courtship in early March, ensuring that egg-laying coincides with insect abundance crucial for feeding nestlings. Tropical birds may breed year-round but often align nesting with rainy seasons when resources are plentiful.

Mating rituals vary widely across species and play a critical role in reproductive success. Some birds engage in elaborate displays: peacocks fan their iridescent tail feathers, while male bowerbirds construct intricate structures to attract females. These behaviors not only facilitate pair bonding but also allow females to select genetically fit mates, indirectly influencing the viability of fertilized eggs.

Differences Among Bird Species in Fertilization Mechanisms

While all birds use internal fertilization, there are notable variations among species:

- Passerines: Small songbirds rely on brief cloacal contact. They typically form monogamous pairs during breeding seasons, with both parents contributing to incubation and chick-rearing.

- Raptors: Hawks and eagles often have long-term pair bonds. Their fertilization process is similar, but mating may occur over several days leading up to egg-laying.

- Waterfowl: Ducks and swans possess phalluses, allowing for forced copulations in some species. This has led to complex co-evolutionary adaptations in female anatomy to control paternity.

- Domestic Poultry: Chickens and turkeys are frequently studied models. In commercial settings, artificial insemination is sometimes used to maximize fertilization rates.

These differences highlight the evolutionary diversity in how birds ensure successful fertilization despite varying ecological pressures.

Myths and Misconceptions About Bird Reproduction

Several common misconceptions persist about how do birds fertilize eggs:

- Myth: Birds fertilize eggs after laying them.

Fact: Fertilization occurs internally, well before the eggshell forms. An unfertilized egg never had contact with sperm. - Myth: All eggs laid by a female bird are fertilized.

Fact: Only eggs produced shortly after mating (or while stored sperm remains viable) are fertilized. Unmated females still lay eggs, but these are infertile. - Myth: Male birds sit on eggs to fertilize them.

Fact: Incubation begins after laying and serves only to warm the embryo, not to fertilize the egg.

Clarifying these misunderstandings helps promote accurate knowledge, especially among amateur birdwatchers and educators.

Observing Fertilization Indirectly: Tips for Birdwatchers and Researchers

Direct observation of avian fertilization is nearly impossible in the wild due to its internal nature and fleeting mating events. However, birdwatchers and researchers can infer successful fertilization through indirect signs:

- Nesting Behavior: The construction of nests and consistent incubation suggest prior mating and likely fertilization.

- Egg Candling: Using a bright light source behind an egg (candling), one can detect blood vessels or embryonic development around day 5–7 in many species.

- Clutch Completion: Many birds delay full incubation until the last egg is laid, resulting in synchronous hatching—evidence of planned reproduction.

- Vocalizations and Pair Bonding: Frequent duetting, feeding between mates, or territorial defense indicate active breeding pairs.

For citizen scientists, recording data such as first egg dates, clutch sizes, and hatching success contributes valuable information to ornithological databases like NestWatch or eBird.

Environmental and Human Impacts on Avian Fertility

Various external factors influence how effectively birds fertilize eggs and raise offspring:

- Habitat Loss: Fragmented habitats reduce population densities, limiting mate availability and increasing inbreeding risks.

- Pollution: Pesticides like DDT historically caused thin-shelled eggs, reducing reproductive success even when fertilization occurred.

- Climate Change: Shifts in seasonal timing may desynchronize breeding with peak food availability, affecting chick survival post-fertilization.

- Urbanization: Artificial lighting and noise pollution can disrupt courtship signals and mating behaviors.

Conservation efforts focused on preserving breeding grounds, minimizing chemical runoff, and creating wildlife corridors help support healthy avian populations capable of successful internal fertilization and reproduction.

Comparative Perspective: Birds vs. Other Animal Groups

It’s useful to contrast how do birds fertilize eggs with mechanisms in other animals:

| Group | Fertilization Method | Egg Type | Parental Care |

|---|---|---|---|

| Birds | Internal | Amniotic, calcified shell | Often biparental |

| Amphibians | External | Gelatinous, no shell | Rare |

| Reptiles | Internal | Amniotic, leathery or calcified | Variable |

| Mammals (except monotremes) | Internal | No egg (viviparous) | High |

| Fish | Mostly external | No shell, aquatic | Low |

This comparison underscores that while internal fertilization is shared with reptiles and mammals, birds uniquely combine this trait with flight-adapted physiology and high parental investment in altricial or precocial young.

Practical Applications: Breeding Birds in Captivity and Conservation Programs

Zoos, aviculture centers, and endangered species recovery programs rely on deep understanding of how do birds fertilize eggs to manage breeding efforts. Techniques include:

- Artificial Insemination: Used in species with low natural mating success, such as California condors.

- Incubator Rearing: Removes eggs from parents to increase hatch rates and allows double-clutching (inducing second clutches).

- Genetic Management: Ensures diverse gene pools and avoids inbreeding depression.

Such interventions have helped recover species like the Mauritius kestrel and Puerto Rican parrot from near extinction.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Do birds need to mate every time they lay an egg?

- No. Female birds can store sperm for several days to weeks, allowing multiple eggs to be fertilized from one mating session.

- Can unfertilized bird eggs hatch?

- No. Only fertilized eggs containing a developing embryo can hatch. Unfertilized eggs lack paternal DNA.

- How soon after mating does a bird lay a fertilized egg?

- Fertilization happens within hours of ovulation. Eggs are typically laid within 24 hours after fertilization.

- Are all eggs in a clutch usually fertilized?

- Not always. Early eggs in a clutch are more likely to be fertilized if mating occurred recently. Later eggs may be infertile if sperm stores are depleted.

- Can you tell if an egg is fertilized just by looking at it?

- No. Externally, fertilized and unfertilized eggs look identical. Candling or breaking open the egg is required to confirm fertilization.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4