If you're wondering how do you get a bird out of a building, the most effective and humane method is to safely guide it outside by reducing indoor distractions and providing a clear flight path to an open exit. This approach—often referred to as passive release or gentle coaxing—is widely recommended by wildlife experts and bird rehabilitators. The key is to remain calm, minimize noise and movement, and use natural light to your advantage by opening exterior doors or windows on the side of the building facing daylight. Birds instinctively fly toward light and open spaces, so creating a visible escape route increases the chances of success without causing harm. Understanding how to get a bird out of a building without injury requires both patience and knowledge of bird behavior, which we'll explore in depth throughout this article.

Why Birds Fly Into Buildings—and Why They Stay

Birds often enter buildings accidentally through open doors, garage entrances, or even broken windows. Once inside, they become disoriented due to reflections, artificial lighting, and lack of visual cues for navigation. Unlike outdoor environments where birds can orient themselves using the sky, horizon, and landmarks, indoor spaces create sensory confusion. This leads to erratic flight patterns as the bird tries to escape, often resulting in collisions with walls, glass, or ceiling fixtures.

Common species found indoors include house sparrows, starlings, swallows, and pigeons—birds that naturally inhabit urban environments. Migratory birds may also enter large commercial buildings during seasonal movements, especially at night when artificial lights attract them—a phenomenon known as fatal light attraction. In residential settings, small songbirds like wrens or finches might dart in while chasing insects near open patio doors.

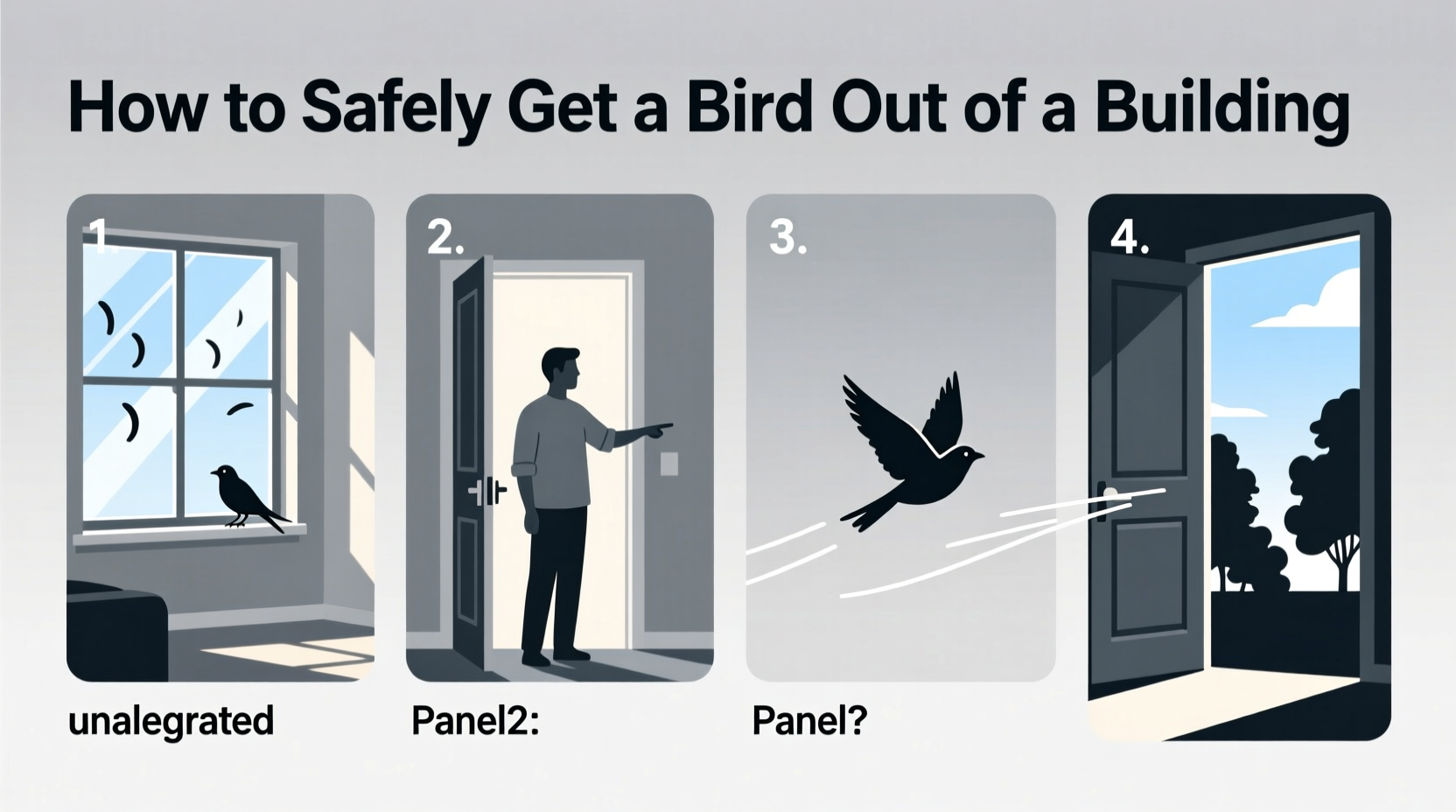

Step-by-Step Guide: How to Get a Bird Out of a Building

Successfully removing a bird from a building involves strategy, timing, and respect for the animal’s instincts. Below is a detailed, step-by-step process based on best practices used by ornithologists and wildlife rescue professionals.

- Stay Calm and Quiet: Sudden movements, loud voices, or attempts to chase the bird will only increase its stress levels, leading to exhaustion or injury. Move slowly and speak softly.

- Isolate the Room: If possible, close off other rooms to confine the bird to one space. This prevents it from flying deeper into the building and makes it easier to control access points.

- Open Exterior Exits: Identify all doors or windows that lead directly outside. Open them wide, preferably on the side of the structure facing natural light. Remove screens if safe to do so.

- Turn Off Interior Lights: Dim or switch off indoor lighting to reduce reflections and help the bird see the outdoor environment more clearly. Use blinds or curtains to darken adjacent rooms.

- Create a Visual Exit Path: Place light-colored sheets or cardboard along interior walls opposite the exit to contrast with dark surfaces. Birds are less likely to fly into light barriers, helping direct them toward the open door.

- Wait Patiently: Give the bird time—sometimes up to an hour—to find its way out. Avoid standing directly in front of the exit; instead, position yourself out of sight or behind a corner.

- Use a Light Beam (Optional): At dusk or in low-light conditions, a flashlight aimed gently toward the exit can act as a beacon. Do not shine it directly at the bird.

When Passive Methods Fail: What to Do Next

If the bird remains trapped after 60–90 minutes, or appears injured, exhausted, or grounded, intervention may be necessary. Here are humane next steps:

- Capture Gently with a Towel or Box: Approach slowly and cover the bird with a soft cloth to calm it. Alternatively, place a cardboard box over it and slide a piece of stiff paper underneath to lift it safely.

- Avoid Bare-Hand Contact: While most common birds do not carry diseases transmissible to humans, gloves or fabric provide protection and reduce stress for the bird.

- Release Outside Immediately: Carry the bird outside and open the container in a sheltered area away from foot traffic, predators, or roads. Allow it to exit on its own.

Note: Never attempt to feed or give water to a trapped bird. Stress suppresses appetite, and improper feeding can cause aspiration or death.

Biology Behind Bird Navigation and Stress Responses

To fully understand how to get a bird out of a building, it helps to know how birds perceive their surroundings. Birds rely heavily on visual cues for orientation. Their eyes are positioned on the sides of their heads (in most species), giving them nearly 300-degree vision but limited depth perception straight ahead. This makes enclosed spaces particularly confusing.

Additionally, birds have a high metabolic rate and rapid heartbeats—some small passerines exceed 500 beats per minute under stress. Prolonged panic can lead to capture myopathy, a condition caused by extreme muscle exertion that can be fatal. This underscores the importance of minimizing handling and exposure time.

Light plays a crucial role. Many birds navigate using polarized light patterns in the sky, which are absent indoors. Artificial lights, especially blue-spectrum LEDs, can disrupt circadian rhythms and attract nocturnal migrants. This explains why birds often circle under eaves or near skylights—they’re responding to misleading stimuli.

Cultural and Symbolic Meanings of Birds Indoors

Beyond biology, the presence of a bird inside a home carries symbolic weight across cultures. In some European traditions, a bird entering a house is seen as an omen—either of impending death or good fortune, depending on the species and context. For example, a robin appearing indoors might symbolize renewal, while an owl could be interpreted as a harbinger.

In Native American beliefs, birds are messengers between worlds. An unexpected visitor may represent spiritual communication or a need for introspection. While these interpretations vary widely, they reflect humanity’s long-standing relationship with avian life—not just as animals, but as symbols of freedom, intuition, and transcendence.

From a psychological perspective, encountering a wild bird in a domestic space can evoke awe or anxiety. Recognizing this emotional dimension helps people respond compassionately rather than reactively, aligning practical action with empathy.

Special Cases: Large Birds and Commercial Spaces

The method for how to get a bird out of a building varies depending on size and setting. Large birds such as hawks, herons, or waterfowl require extra caution due to their strength and sharp talons or beaks. If a raptor enters a warehouse or gymnasium, evacuate the area and contact local wildlife authorities immediately. Attempting to capture such birds without training risks injury to both human and animal.

In commercial or institutional buildings—like schools, malls, or airports—integrated pest management (IPM) plans should include protocols for bird entry incidents. These typically involve designated staff trained in non-lethal removal, access to netting or containment tools, and partnerships with licensed rehabilitators.

For multi-story structures with atriums or glass corridors, architectural design plays a major role. Reflective surfaces often contribute to bird strikes and entrapment. Solutions include installing UV-reflective decals, external shading devices, or fritted glass—all of which improve visibility for birds while maintaining aesthetics.

| Bird Type | Common Entry Points | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| Small Songbirds (sparrows, finches) | Patio doors, open windows | Open exit, turn off lights, wait |

| Pigeons/Doves | Ventilation shafts, loading docks | Guide toward light, avoid chasing |

| Bats (often mistaken for birds) | Eaves, attic vents | Contact animal control—do not handle |

| Raptors (owls, hawks) | Atriums, skylights | Evacuate area, call wildlife expert |

| Migratory birds (warblers, thrushes) | Lighted towers, office complexes | Shut off unnecessary lights at night |

Preventing Future Incidents: Long-Term Strategies

Once you’ve successfully figured out how to get a bird out of a building, consider preventive measures to reduce recurrence:

- Install Mesh Screens or Grilles: On open-air entries like garages or breezeways, fine mesh can block entry while allowing airflow.

- Use Motion-Sensor Lighting: Reduces nighttime illumination that attracts flying birds.

- Add Window Markers: Decals spaced no more than 2 inches apart vertically or 4 inches horizontally deter collisions.

- Seal Gaps and Vents: Inspect rooftops, chimneys, and soffits regularly for potential nesting sites.

- Participate in Lights Out Programs: Cities like New York, Chicago, and Toronto run seasonal initiatives encouraging building owners to dim lights during migration periods (spring and fall).

Common Misconceptions About Trapped Birds

Several myths persist about what to do when a bird is inside a building. Let’s clarify:

- Myth: Chasing the bird helps. False. Panic increases injury risk. Patience yields better results.

- Myth: All birds carry disease. Most urban birds pose minimal health risk if brief contact occurs.

- Myth: You should feed a trapped bird. No. Stress inhibits digestion, and incorrect food can be harmful.

- Myth: Birds can find their way out easily. Not true in complex interiors. They need guidance.

When to Call a Professional

While most situations can be managed independently, certain scenarios require expert assistance:

- The bird is visibly injured (limping, unable to stand, bleeding)

- It belongs to a protected or endangered species

- It's a large or aggressive bird (e.g., hawk, heron)

- Multiple birds are involved (indicating a nest or colony)

- You suspect it has rabies-like symptoms (extremely rare; more likely in bats)

Contact local wildlife rehabilitation centers, animal control agencies, or bird conservation organizations for support. Many offer free advice or on-site help.

Frequently Asked Questions

- How long can a bird survive inside a building?

- Most small birds can survive 24–48 hours without food or water, but stress shortens this window. Immediate release is critical.

- Will a bird eventually find its way out on its own?

- Sometimes, but not reliably. Without directional cues, birds may exhaust themselves trying to escape through glass.

- Can I use a net to catch the bird?

- Only if experienced. Improper use can injure wings or cause panic. A towel or box is safer for amateurs.

- What if the bird won’t leave even after opening the door?

- Ensure there’s a strong light gradient. Close interior doors, turn off lights, and wait quietly. It may take time.

- Are certain times of year worse for bird intrusions?

- Yes. Spring and fall migrations increase incidents, especially during dawn and dusk. Breeding season (late winter to early summer) also raises activity near nests.

Understanding how to get a bird out of a building goes beyond simple problem-solving—it reflects our responsibility toward coexisting with wildlife in shared environments. By combining biological insight, humane techniques, and preventive planning, we can ensure safe outcomes for both people and birds. Whether dealing with a sparrow in the living room or managing avian safety in large facilities, the principles remain the same: observe, guide, and respect.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4