Yes, birds are reptiles in the modern biological classification system. This conclusion is based on evolutionary biology and phylogenetic taxonomy, which reveal that birds share a common ancestor with crocodilians and other reptiles. The question is bird a reptile has evolved from a simple classification puzzle into a cornerstone of understanding vertebrate evolution. Today, scientists widely accept that birds are not just related to reptiles—they are, in fact, a specialized subgroup of reptiles, specifically within the clade Archosauria. This means that when we ask is a bird considered a reptile, the scientifically accurate answer is yes.

Understanding Modern Taxonomy: Why Birds Are Reptiles

The traditional view of classifying animals into five main classes—mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and fish—is increasingly outdated in light of genetic and fossil evidence. Under this older system, birds were separated from reptiles due to obvious physical differences such as feathers, warm-bloodedness, and flight. However, modern cladistics—the method of classifying organisms based on shared ancestry—has reshaped our understanding.

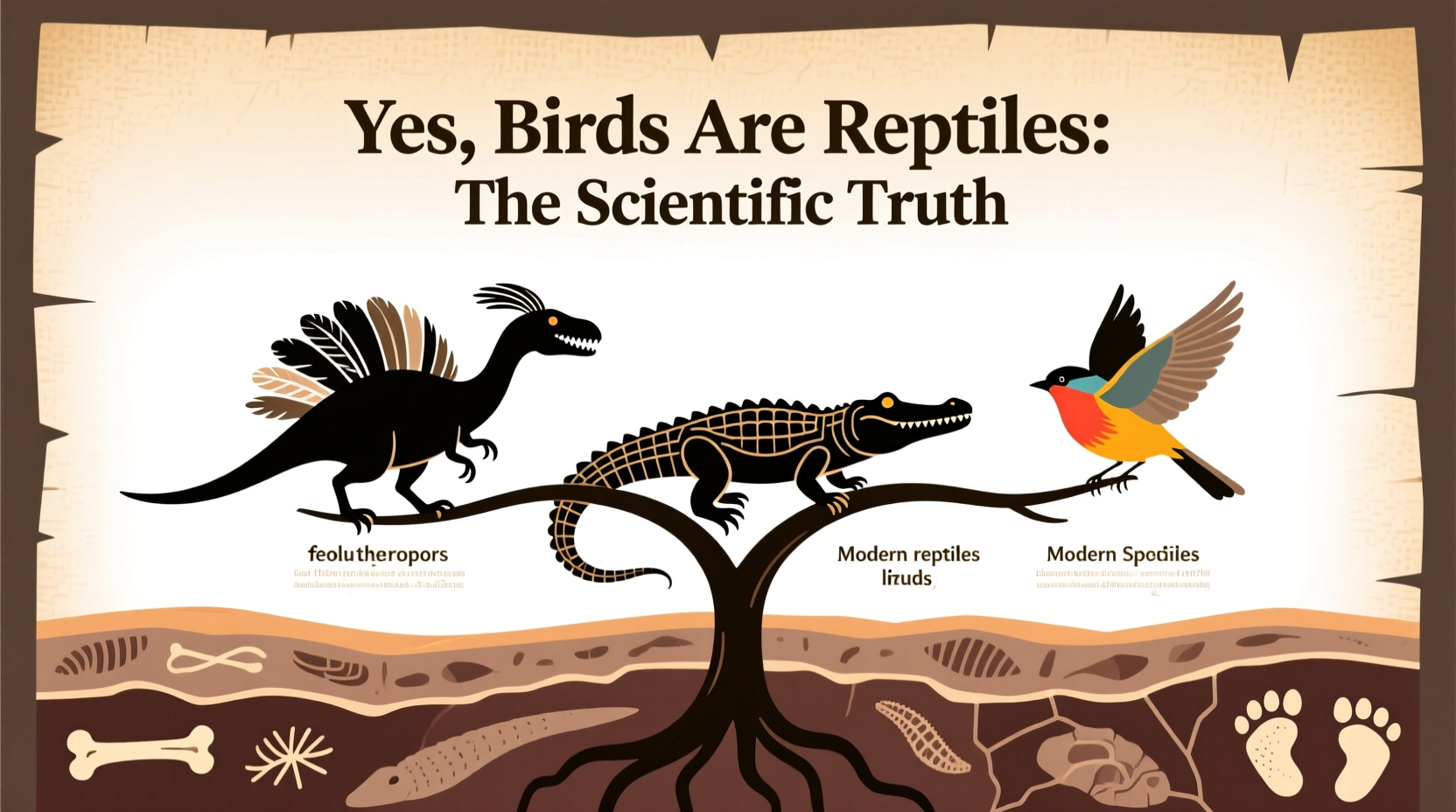

In cladistic terms, a group must include all descendants of a common ancestor to be considered natural or monophyletic. Since birds evolved from small theropod dinosaurs during the Jurassic period, and dinosaurs are nested within the reptile lineage, excluding birds from Reptilia would make the reptile group paraphyletic (incomplete). Therefore, to maintain scientific accuracy, birds are now classified within Reptilia.

This reclassification does not mean birds are “just like” lizards or snakes, but rather that they represent a highly derived branch of the reptilian family tree. Just as humans are mammals despite significant differences from platypuses, birds are reptiles despite their unique adaptations.

Evolutionary Origins: From Dinosaurs to Modern Birds

The link between birds and reptiles is most clearly demonstrated through paleontology. Fossils such as Archaeopteryx, discovered in the 19th century, exhibit both avian features (feathers, wings) and reptilian traits (teeth, long bony tail, clawed fingers). These transitional fossils provide strong evidence that birds descended from small, bipedal carnivorous dinosaurs known as maniraptoran theropods.

Further discoveries in China during the 1990s and 2000s—including feathered dinosaurs like Sinosauropteryx, Microraptor, and Anchiornis—have solidified this connection. These species had feathers but could not fly, suggesting that feathers first evolved for insulation or display before being co-opted for flight.

Genetic studies also support this evolutionary narrative. Comparative genomics shows that birds share more DNA sequences with crocodiles than crocodiles do with turtles or lizards, reinforcing that birds and crocs are sister groups within Archosauria. This makes birds more closely related to crocodiles than either is to other reptiles.

Biological Traits: Comparing Birds and Reptiles

While birds possess several advanced traits not found in most reptiles, many fundamental biological characteristics align them closely with reptilian physiology.

| Trait | Birds | Non-Avian Reptiles |

|---|---|---|

| Skull Structure | Single temporal fenestra (diapsid pattern) | Diapsid skull with two openings |

| Skin Covering | Feathers (modified scales) | Scales made of keratin |

| Egg Type | Amniotic, calcified shell | Amniotic, leathery or calcified shell |

| Heart Chambers | Four-chambered heart | Most have three chambers; crocodilians have four |

| Metabolism | Endothermic (warm-blooded) | Ectothermic (cold-blooded), except some active species |

| Respiratory System | Lungs with air sacs, unidirectional airflow | Lungs with tidal airflow |

One key distinction often cited is endothermy—birds generate internal heat, while most reptiles rely on external sources. However, some large reptiles can maintain stable body temperatures through thermal inertia (gigantothermy), and certain species like the leatherback sea turtle and some monitor lizards show semi-endothermic tendencies. Thus, metabolism alone doesn’t exclude birds from being reptiles.

Moreover, feathers themselves are modified scales. Embryological studies show that both feathers and reptilian scales develop from the same type of epidermal placodes and are composed primarily of beta-keratin, the same protein found in reptile skin. This developmental continuity further supports the idea that is bird a reptile isn't merely theoretical—it's grounded in observable biology.

Cultural and Symbolic Perceptions vs. Scientific Reality

Culturally, birds occupy a unique space distinct from reptiles. In mythology, religion, and literature, birds often symbolize freedom, transcendence, and the soul—qualities rarely associated with snakes or lizards. Ancient Egyptians revered the ibis and falcon as divine messengers; Native American tribes used eagle feathers in spiritual ceremonies; and doves represent peace across many cultures.

In contrast, reptiles—especially snakes—are frequently depicted as sinister, deceptive, or primitive. This symbolic divide reinforces the public perception that birds and reptiles are fundamentally different. But science transcends symbolism. Recognizing that birds are reptiles challenges us to rethink how we categorize nature—not by appearance or cultural meaning, but by evolutionary history.

Interestingly, indigenous knowledge systems sometimes reflect this deeper connection. Some Aboriginal Australian traditions describe ancestral beings that blend bird and reptile characteristics, echoing the evolutionary truth that these forms are deeply intertwined.

Implications for Birdwatchers and Naturalists

For amateur and professional birdwatchers, understanding that birds are reptiles adds depth to every observation. When you spot a red-tailed hawk soaring overhead or hear a mockingbird mimic other species, you're witnessing a living dinosaur—a highly adapted reptile that mastered flight and colonized nearly every habitat on Earth.

This perspective enhances field identification and ecological interpretation. For example:

- Nesting behavior: Many birds lay eggs in nests similar to those of crocodilians, guarding them with parental care unseen in most reptiles but present in some dinosaurs.

- Locomotion: The upright posture of birds mirrors that of theropod dinosaurs, unlike the sprawling gait of lizards and snakes.

- Vocalizations: While most reptiles are quiet, birds produce complex songs—yet recent research suggests some dinosaurs may have used closed-mouth vocalizations akin to cooing, a precursor to avian song.

Birdwatchers can use apps like eBird or Merlin Bird ID to log sightings, contribute to citizen science, and explore evolutionary relationships via built-in taxonomic trees. Understanding that is bird a reptile helps contextualize data collection within broader biodiversity frameworks.

Common Misconceptions About Birds and Reptiles

Despite growing scientific consensus, several myths persist:

- Misconception 1: “Birds can’t be reptiles because they’re warm-blooded.”

Reality: Metabolic strategy doesn’t define class membership. Mammals are warm-blooded too, yet no one questions their classification. Moreover, some reptiles exhibit regional endothermy. - Misconception 2: “Reptiles don’t have feathers, so birds aren’t reptiles.”

Reality: Feathers evolved from reptilian scales. The presence of a derived trait doesn’t remove an organism from its ancestral group. - Misconception 3: “If birds are reptiles, then why are they in a separate class?”

Reality: Traditional Linnaean taxonomy used morphological differences to separate Aves from Reptilia. Modern phylogenetics prioritizes evolutionary descent over physical form.

These misconceptions highlight the gap between public understanding and current science. Educators, zoos, and wildlife documentaries play a crucial role in closing it.

How to Teach and Communicate This Concept

Explaining that birds are reptiles requires sensitivity to prior knowledge. Here are effective strategies:

- Use analogies: Compare bird-reptile relations to humans and primates—we are mammals, and more specifically, primates. Similarly, birds are reptiles, and more specifically, theropod dinosaurs.

- Show transitional fossils: Visuals of Archaeopteryx or Velociraptor with quill knobs help illustrate the continuum.

- Leverage interactive tools: Phylogenetic tree builders online allow users to drag species and see evolutionary splits.

- Acknowledge discomfort: Admit that calling a robin a reptile feels strange—but so did accepting that whales are mammals once upon a time.

Museums like the American Museum of Natural History and the Smithsonian now label birds as “living dinosaurs” or “avian reptiles,” helping normalize the concept.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are birds cold-blooded?

No, birds are warm-blooded (endothermic), which distinguishes them from most reptiles. However, thermoregulation method does not override evolutionary lineage.

If birds are reptiles, should they be kept with lizards and snakes?

No—biological classification doesn’t imply identical care needs. Birds require different diets, enclosures, and social environments than non-avian reptiles.

Do all scientists agree that birds are reptiles?

Yes, among evolutionary biologists and paleontologists, there is broad consensus. Disagreement exists mainly in educational contexts using outdated taxonomy.

What’s the correct scientific term for birds if they’re reptiles?

Birds are part of the clade Avialae within the larger group Sauropsida, which includes all reptiles. They are often referred to as “avian reptiles,” while others are “non-avian reptiles.”

Does this mean I should call a sparrow a lizard?

No. While sparrows are reptiles in evolutionary terms, colloquially it makes sense to use common names. Scientific accuracy doesn’t replace practical language.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4