Yes, the chicken is a bird—this is a fundamental truth in both biological classification and everyday understanding. Scientifically known as Gallus gallus domesticus, the chicken belongs to the class Aves, which includes all birds. As a domesticated fowl with feathers, a beak, wings, and the ability to lay eggs, the chicken exhibits all the defining characteristics of avian species. While many people may wonder is the chicken really a bird, especially given its limited flight capability and widespread role in agriculture, the answer remains unequivocally yes. This article explores the biological, evolutionary, cultural, and practical aspects that confirm the chicken’s status as a true bird, while also addressing common misconceptions and offering insights for bird enthusiasts and curious minds alike.

Biological Classification: Why Chickens Are Birds

To understand why chickens are classified as birds, it's essential to examine the taxonomic system used in biology. All living organisms are categorized into a hierarchy: kingdom, phylum, class, order, family, genus, and species. Chickens fall under the kingdom Animalia, phylum Chordata, and class Aves—the scientific name for birds.

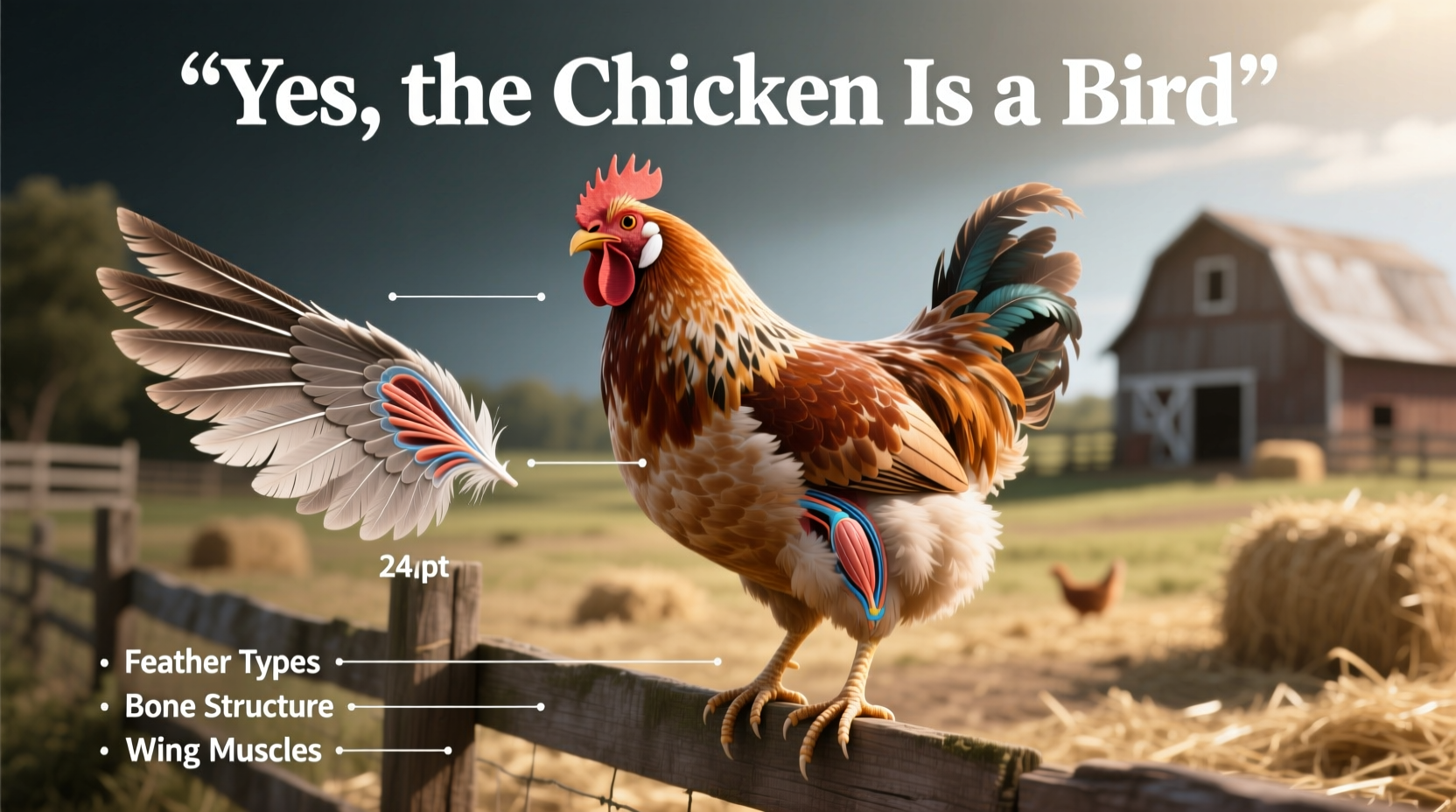

The class Aves is defined by several key traits, all of which chickens possess:

- Feathers: Chickens are covered in feathers, one of the most distinctive features of birds. No other animal group has true feathers.

- Beaks without teeth: Chickens have beaks and lack teeth, aligning them with other birds.

- Laying hard-shelled eggs: Like all birds, chickens reproduce by laying eggs with calcified shells.

- High metabolic rate and warm-bloodedness: Chickens maintain a constant internal body temperature, a hallmark of endothermic animals like birds and mammals.

- Wings: Though modern domestic chickens rarely fly, they have wings derived from forelimbs, a trait shared with all birds.

- Skeletal adaptations for flight: Even flightless birds like chickens retain lightweight bones and a keeled sternum, though reduced compared to flying species.

Despite being selectively bred for meat and egg production—which has led to heavier bodies and reduced flight ability—chickens still exhibit the anatomical blueprint of birds. Their closest wild ancestor, the red junglefowl (Gallus gallus) of Southeast Asia, is a fully capable flyer, further supporting their avian lineage.

Evolutionary Origins: From Dinosaurs to Domestication

One of the most fascinating aspects of avian biology is the evolutionary link between birds and dinosaurs. Modern birds, including chickens, are considered direct descendants of theropod dinosaurs—a group that includes Tyrannosaurus rex and Velociraptor. Fossil evidence, genetic studies, and skeletal similarities all support this connection.

Chickens, like all birds, evolved from small, feathered dinosaurs over 150 million years ago. The discovery of fossils such as Archaeopteryx—a creature with both reptilian and avian features—provides a transitional model for how flight and feathers developed. Over time, natural selection favored adaptations that enhanced gliding and eventually powered flight.

Domestication of the chicken began around 8,000 years ago in Southeast Asia, primarily from the red junglefowl. Humans selected individuals with desirable traits such as docility, larger body size, and increased egg production. This artificial selection has altered the chicken’s appearance and behavior but not its fundamental biology. Genetically, chickens share a significant portion of their DNA with other birds and even with reptiles, reinforcing their place in the evolutionary tree of life.

Cultural and Symbolic Significance of Chickens

Beyond biology, chickens hold deep cultural and symbolic meaning across civilizations. In many societies, the chicken is more than just livestock—it represents fertility, vigilance, and renewal.

In ancient Egypt, chickens were associated with the sun god Ra and seen as symbols of resurrection. In Chinese culture, the rooster is one of the twelve zodiac animals and signifies honesty, punctuality, and confidence. It is also believed to ward off evil spirits with its morning call.

In Western traditions, the phrase “rise with the rooster” reflects the bird’s role as a natural alarm clock, symbolizing diligence and awakening. Conversely, expressions like “playing chicken” or calling someone a “chicken” (meaning cowardly) reveal more complex, sometimes contradictory, cultural attitudes.

Religious contexts also feature chickens. In some African and Afro-Caribbean spiritual practices, chickens are used in rituals as offerings. In Judaism, the practice of kapparot involves swinging a chicken over one’s head before Yom Kippur as a symbolic atonement ritual (though this is controversial and often performed with money instead today).

These diverse interpretations underscore how the chicken, despite its humble status in industrial farming, occupies a rich symbolic space in human history.

Common Misconceptions About Chickens and Bird Identity

Despite clear biological evidence, some people question whether chickens are truly birds. These doubts often stem from observable behaviors and physical traits that differ from typical songbirds or raptors.

Misconception 1: “Chickens can’t fly, so they’re not real birds.”

While most domestic chickens cannot sustain long flights, they can flap short distances to escape predators or reach roosts. Flightlessness is not uncommon in birds—consider ostriches, emus, and penguins, all of which are flightless yet unquestionably birds.

Misconception 2: “Chickens are too different from wild birds.”

This belief arises from selective breeding. Over centuries, humans have exaggerated certain traits in chickens, leading to breeds with oversized breasts or unusual plumage. However, these changes do not alter their classification. Just as dog breeds vary widely but remain Canis lupus familiaris, chickens remain Gallus gallus domesticus.

Misconception 3: “If chickens are birds, why don’t we treat them like other birds?”

This is more an ethical or perceptual issue than a biological one. Chickens are among the most numerous birds on Earth—over 25 billion exist at any time—but they are largely viewed as food sources rather than wildlife. This utilitarian perspective often overshadows their biological identity.

Observing Chickens as Birds: Tips for Birdwatchers

For bird enthusiasts, observing chickens can offer unique insights into avian behavior, especially when comparing domestic and wild fowl. Here are practical tips for viewing chickens through a birder’s lens:

- Visit heritage farms or sanctuaries: Many animal sanctuaries house heritage chicken breeds that display more natural behaviors than commercial broilers.

- Watch for social hierarchies: Chickens establish a “pecking order,” a term now used in psychology to describe dominance structures. Observing this can provide insight into avian social intelligence.

- Listento vocalizations: Chickens make over 30 distinct calls, including warning cries, food calls, and mating sounds. Learning these can enhance your understanding of avian communication.

- Compare anatomy: Use binoculars to study feather patterns, wing structure, and gait. Compare these with wild birds like pheasants or turkeys, which are closely related.

- Document behavior: Keep a journal of feeding, dust-bathing, and nesting habits—many of which are shared with wild ground-dwelling birds.

While chickens may not migrate or sing complex songs, they are still valuable subjects for understanding bird biology and behavior.

Chickens in Urban and Backyard Settings

In recent years, backyard chicken keeping has surged in popularity across North America, Europe, and Australia. Cities like Portland, Seattle, and London allow residents to keep small flocks, provided they follow local ordinances.

Keeping chickens offers educational opportunities about bird care, egg production, and sustainable living. However, prospective owners should research zoning laws, coop requirements, predator protection, and healthcare needs. Unlike wild birds, domestic chickens rely entirely on humans for food, shelter, and safety.

Backyard chicken owners often report increased appreciation for avian life. Children learn where eggs come from, and adults gain respect for the intelligence and individuality of chickens—traits often overlooked in factory farming systems.

Scientific Research and Chickens

Chickens play a vital role in scientific research. Due to their well-understood genetics and rapid development, they are used in studies ranging from embryology to virology.

Fertilized chicken eggs are commonly used to grow viruses for vaccine production, including flu vaccines. Developmental biologists study chick embryos to understand organ formation and genetic regulation. Additionally, chickens are models for studying bone growth, muscle development, and even behavioral neuroscience.

Genome sequencing has revealed that chickens share about 60% of their genes with humans, making them surprisingly relevant to medical research. Their status as birds does not diminish their scientific value—in fact, it enhances it, providing a critical evolutionary comparison point between mammals and non-mammalian vertebrates.

| Feature | Chickens | Typical Wild Birds (e.g., Sparrow) | Flightless Birds (e.g., Ostrich) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classification | Aves | Aves | Aves |

| Feathers | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Flight Ability | Limited (short bursts) | Strong | None |

| Egg Laying | Yes (frequent) | Yes (seasonal) | Yes (large eggs) |

| Social Structure | Pronounced pecking order | Moderate hierarchy | Complex herds |

Frequently Asked Questions

- Is a chicken considered a bird scientifically?

- Yes, chickens are scientifically classified as birds under the class Aves. They share all major avian characteristics, including feathers, egg-laying, and a beak.

- Why do some people think chickens aren’t birds?

- Because chickens are flightless and heavily domesticated, some assume they are biologically different. However, flightlessness is common among birds, and domestication doesn’t change species classification.

- Can chickens fly like other birds?

- Most domestic chickens can only fly short distances—usually just enough to reach a perch or escape danger. Their wild ancestors, however, are much more capable fliers.

- Are chickens related to dinosaurs?

- Yes, chickens are direct descendants of theropod dinosaurs. Genetic and fossil evidence confirms that modern birds, including chickens, evolved from small, feathered dinosaurs.

- Should chickens be treated like other birds in conservation efforts?

- While chickens are not endangered, their welfare is increasingly a concern. Ethically, recognizing them as sentient birds supports better treatment in agriculture and urban settings.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4