The feet of birds are scientifically referred to as avian feet, and more specifically, the bones in a bird's foot are known collectively as the tarsometatarsus and phalanges. When people ask, 'what are birds feet called,' they're often seeking not just the correct biological terminology but also an understanding of how these specialized limbs support flightless movement, perching, swimming, and predation. Unlike mammals, birds lack hands and arms as we know them; instead, their lower limbs end in highly adapted feet that reflect their ecological niche—whether that’s gripping tree branches, wading through marshes, or snatching prey mid-air.

Anatomical Breakdown: What Makes Up a Bird’s Foot?

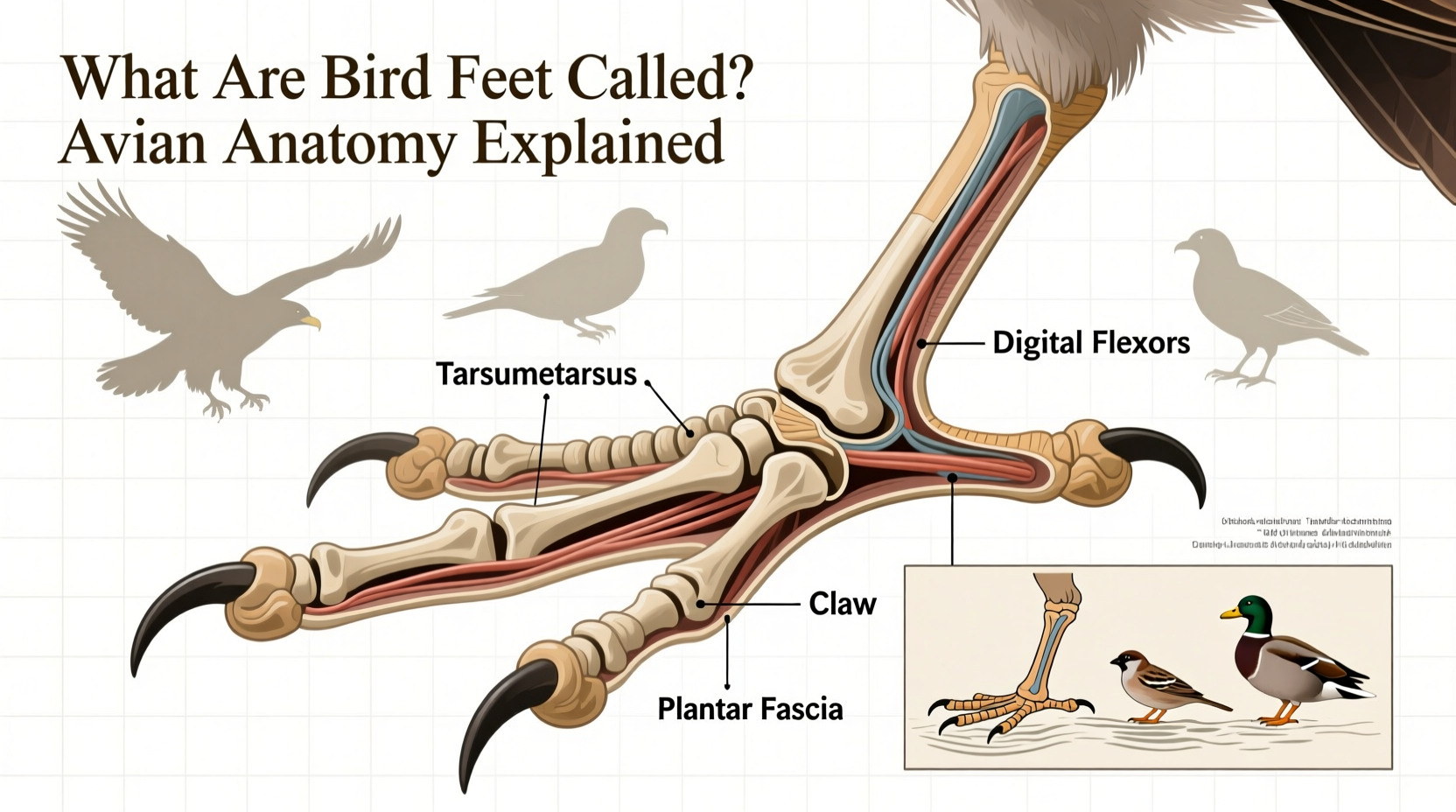

Birds have a unique skeletal structure in their lower extremities. The visible portion of a bird's leg—the part below the body that ends in toes—is composed of several key components:

- Tibiotarsus: The upper bone formed by the fusion of the tibia and proximal tarsal bones.

- Tarsometatarsus: A long, fused bone equivalent to the metatarsals and distal tarsals in humans. This is the main shaft you see extending down before the toes begin.

- Toes (Digits): Most birds have four toes, though the arrangement varies significantly between species. These digits contain phalanges, similar to fingers or toes in mammals.

The entire structure below the ankle joint is technically the foot, even if it appears elongated or knee-like from a human perspective. One common misconception is that birds walk on their toes—a concept known as digitigrade locomotion—but in reality, birds use a semi-digitigrade stance due to the complex hinge of the ankle and reversed knee appearance.

Types of Bird Feet and Their Functions

Bird feet are marvels of evolutionary adaptation. Depending on habitat and behavior, different species have developed distinct foot morphologies. Below are the primary types of avian feet and their associated functions:

| Type of Foot | Toe Arrangement | Function | Example Species |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anisodactyl | Three toes forward, one backward | Perching securely on branches | Songbirds (e.g., robins, sparrows) |

| Zygodactyl | Two toes forward, two backward | Climbing trees and grasping bark | Woodpeckers, cuckoos, owls |

| Syndactyl | Fused third and fourth toes | Support during flight and walking | Kingfishers, bee-eaters |

| Pamprodactyl | All four toes can point forward | Grasping prey mid-flight | Swifts, nightjars |

| Webbed (Palmate) | Front three toes connected by skin | Swimming efficiently | Ducks, geese, gulls |

| Lobate | Toes with fleshy lobes | Walking on soft mud and swimming | Grebes, coots |

| Raptorial | Powerful talons with curved claws | Catching and killing prey | Eagles, hawks, falcons |

Cultural and Symbolic Significance of Bird Feet

Beyond biology, bird feet carry symbolic weight across cultures. In many Indigenous traditions, eagle talons represent strength, spiritual connection, and divine authority. For example, among some Native American tribes, eagle feathers and talons are used in ceremonial regalia, symbolizing honor and bravery. However, possession of such items is regulated under laws like the U.S. Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act, emphasizing both cultural reverence and conservation ethics.

In mythology, bird feet—especially those of raptors—are often linked to power and omniscience. The Roman god Jupiter was depicted with an eagle at his side, its sharp talons underscoring imperial dominance. Similarly, in Hindu iconography, Garuda, the mount of Vishnu, possesses powerful avian limbs representing swiftness and divine intervention.

From a modern symbolic standpoint, phrases like 'having eagle eyes' extend into metaphors about perception, but less commonly do we hear references to feet—despite their critical role in survival. Understanding what birds' feet are called and how they function adds depth to these symbols, grounding mythological imagery in biological reality.

How Bird Feet Aid in Survival and Adaptation

The form and function of avian feet directly influence a bird’s ability to thrive in its environment. Consider the following adaptations:

Perching Mechanism in Songbirds

Many small birds, such as finches and warblers, possess an automatic perching reflex. When a bird lands on a branch, its body weight causes tendons in the leg to tighten, curling the toes around the perch without muscular effort. This allows them to sleep safely without falling. This mechanism answers a frequently searched question: how do birds stay on branches while sleeping?

Swimming Efficiency in Waterfowl

Ducks and geese have palmate feet—webbing between the front three toes—that act like paddles. This increases surface area and propulsive force in water. Interestingly, the same webbing makes terrestrial movement less efficient, which explains why ducks waddle. Some divers, like grebes, have evolved lobate toes instead, allowing them to swim silently and maneuver precisely underwater.

Predatory Power in Raptors

Eagles, hawks, and owls rely on raptorial feet equipped with sharp talons. These claws can exert hundreds of pounds per square inch of pressure, enabling the bird to pierce vital organs and carry prey aloft. Observing a red-tailed hawk’s foot up close reveals how each toe is designed for maximum grip and puncture efficiency.

Misconceptions About Bird Legs and Feet

One of the most widespread misconceptions is that the joint bending backward on a bird is its knee. In fact, what looks like a reverse knee is actually the ankle joint. The true knee is located higher up, hidden beneath feathers near the body. This confusion arises because birds’ femurs are short and internalized, making the long lower leg appear leggy and inverted.

Another myth is that all birds have the same number of toes. While most have four, some species have only three (like swifts) or even two (such as ostriches). Ostriches, being flightless, evolved a bipedal running form with two toes—one large and weight-bearing, the other smaller—optimized for speed across savannas.

Additionally, people often assume bird feet are cold and uncomfortable, especially in winter. However, birds have a specialized circulatory system called countercurrent heat exchange, where warm arterial blood heats cooler venous blood returning from the feet, minimizing heat loss. This adaptation allows ducks to stand on ice without freezing.

Practical Tips for Observing Bird Feet While Birdwatching

For amateur ornithologists and birdwatchers, identifying birds by their feet can enhance field observation skills. Here are actionable tips:

- Use binoculars or a spotting scope: Focus on the feet when a bird is perched or wading. Look for toe arrangement, color, length, and presence of webbing or spurs.

- Photograph feet when possible: Take clear photos from multiple angles. Later, compare with field guides or online databases like Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s All About Birds.

- Note behavioral clues: Does the bird scratch the ground? Climb vertically? Swim with webbed propulsion? Behavior often correlates with foot type.

- Check for seasonal changes: Some birds, like American coots, may appear to change foot color during breeding season (brighter frontal shields and redder legs).

- Avoid misidentification based on leg length alone: Herons and storks both have long legs, but herons typically retract their necks in flight, while storks do not—yet both have syndactyl-like toes suited for wading.

Conservation and Health Indicators

Bird feet can serve as indicators of environmental health. Deformities such as crossed toes, missing digits, or swollen joints may signal pollution, disease (like avian pox), or injury from human-made hazards (e.g., fishing line entanglement). Researchers studying urban bird populations often document foot abnormalities to assess ecosystem stress.

Moreover, invasive species like the European starling compete with native birds for nesting cavities, sometimes damaging feet during aggressive encounters. Monitoring foot injuries in wild populations helps wildlife biologists track interspecies conflict and habitat pressures.

Conclusion: Why Knowing What Bird Feet Are Called Matters

Understanding what birds' feet are called goes beyond memorizing terms like tarsometatarsus or phalanges. It opens a window into evolutionary biology, ecological adaptation, and cultural symbolism. Whether you're a student, birder, or nature enthusiast, recognizing the diversity and functionality of avian feet enriches your appreciation of these remarkable creatures. From the silent grip of an owl’s zygodactyl foot to the powerful strike of an osprey’s talons, every detail tells a story of survival shaped by millions of years of natural selection.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- What are bird feet scientifically called?

- The bones in a bird's foot are primarily the tarsometatarsus and phalanges. Collectively, this structure is referred to as the avian pes or simply the bird's foot.

- Do all birds have the same number of toes?

- No. Most birds have four toes, but arrangements vary. Ostriches have two, while some birds like woodpeckers have two forward and two backward (zygodactyl).

- Why do bird legs look like they bend backward?

- That joint is actually the ankle, not the knee. The real knee is higher up, concealed by feathers. The long visible segment is the tarsometatarsus.

- Can birds feel cold in their feet?

- Birds minimize heat loss through countercurrent circulation. Their feet stay just above freezing, reducing thermal loss while preventing frostbite.

- How can I identify birds by their feet?

- Observe toe arrangement, presence of webbing, claw shape, and color. Combine this with behavior—perching, swimming, climbing—to narrow down species.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4