A sandpiper bird is a small to medium-sized wading bird belonging to the family Scolopacidae, known for its slender bill, long legs, and distinctive feeding behavior along shorelines. Often seen darting across sandy beaches or probing mudflats, sandpipers are a common sight during migration seasons and are celebrated among birdwatchers for their agility and wide distribution. The term 'what is a sandpiper bird' leads many nature enthusiasts to explore not only its physical traits but also its ecological role and symbolic presence in various cultures. These birds are essential indicators of wetland health and play a vital part in coastal ecosystems.

Biology and Taxonomy of Sandpiper Birds

Sandpipers are part of the larger order Charadriiformes, which includes shorebirds such as plovers, curlews, and snipes. Within the family Scolopacidae, there are over 80 species commonly referred to as sandpipers, though they are spread across multiple genera including Calidris, Tringa, and Actitis. One of the most widespread species is the Actitis hypoleucos, known as the common sandpiper, found across Europe and Asia, while the Calidris alba, or sanderling, is frequently observed on North American coasts.

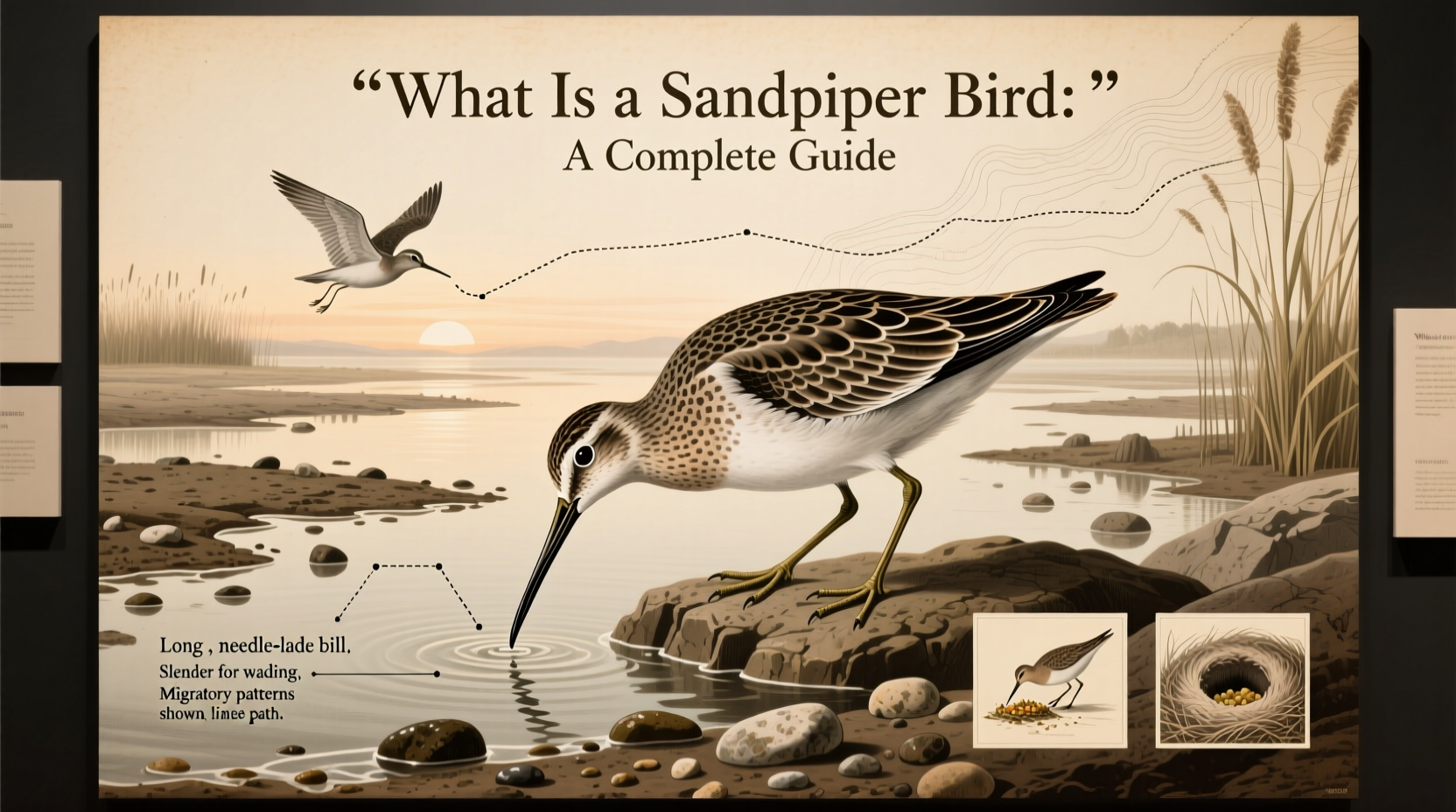

Physically, sandpipers share several adaptations suited to their environment. Most have long, thin bills that allow them to probe into sand or mud to extract invertebrates like worms, crustaceans, and mollusks. Their legs vary in length depending on the species and preferred habitat—those foraging in deeper water tend to have longer legs. Plumage is typically cryptic, with mottled browns, grays, and whites providing camouflage against predators. During breeding season, some species develop more vibrant patterns to attract mates.

These birds are migratory, with many species traveling thousands of miles between breeding grounds in the Arctic tundra and wintering areas in temperate or tropical regions. For example, the semipalmated sandpiper (Calidris pusilla) breeds in northern Canada and Alaska and migrates all the way to South America, relying on key stopover sites like the Bay of Fundy to refuel.

Habitat and Distribution

Sandpipers inhabit a variety of wetland environments, including tidal flats, estuaries, marshes, riverbanks, and sandy beaches. While often associated with coastal regions, some species breed inland in boreal forests or tundra. Their global distribution spans every continent except Antarctica, making them one of the most widely dispersed groups of shorebirds.

The availability of food and suitable nesting sites heavily influences their seasonal movements. In North America, prime sandpiper viewing locations include Cape May (New Jersey), Bolivar Flats (Texas), and the Copper River Delta (Alaska). In Europe, the Wash estuary in England and the Wadden Sea along the North Sea coast support large populations during migration.

Wetland conservation is crucial for sandpiper survival. Habitat loss due to coastal development, pollution, and climate change poses significant threats. Rising sea levels can inundate nesting areas, while human disturbance at beaches may disrupt feeding and resting behaviors.

Behavior and Feeding Habits

One of the most recognizable traits of sandpipers is their rapid, staccato-like feeding motion. They use a technique called 'probing,' where they insert their bills into soft substrates to detect prey by touch. Some species, like the sanderling, exhibit a 'run-stop-probe' pattern, chasing waves as they recede to catch exposed invertebrates.

Social behavior varies by species and season. Many sandpipers are highly gregarious outside the breeding season, forming large flocks that provide protection from predators through collective vigilance. During breeding, however, they become territorial and solitary. Males often perform aerial displays to defend nesting sites and attract females.

Nesting typically occurs on the ground, with simple scrapes lined with vegetation. Both parents may share incubation duties, although this varies. Chicks are precocial—able to walk and feed themselves shortly after hatching—but remain under parental care until fledging.

Identification Tips for Birdwatchers

Identifying sandpipers can be challenging due to their similar appearances and overlapping ranges. However, careful observation of size, bill shape, leg color, plumage patterns, and behavior can help distinguish species. Here are key features to note:

- Bill length and curvature: Short and straight in the least sandpiper; longer and slightly upturned in the dunlin.

- Leg color: Yellowish in the solitary sandpiper; black in the ruddy turnstone.

- Flight pattern: Some species show white wing stripes or rump patches when flying.

- Vocalizations: Calls range from high-pitched peeps to trills and chatters, useful for identification in low visibility.

Field guides and mobile apps like Merlin Bird ID or eBird can assist in real-time identification. Using binoculars or a spotting scope enhances accuracy, especially when observing distant flocks.

| Species | Length (in) | Wingspan (in) | Key Features | Migration Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sanderling | 7–8 | 15–16 | Pale in winter, runs fast on beaches | Arctic to South America |

| Spotted Redshank | 12–13 | 24–26 | Long red legs, dark breeding plumage | Northern Europe to Africa |

| Western Sandpiper | 5.5–6.7 | 13–14 | Bulbous bill tip, rusty head in spring | Alaska to southern U.S./Mexico |

| Common Sandpiper | 7–8 | 18–20 | Teetering gait, white shoulder stripe | Europe/Asia to Africa/South Asia |

Cultural and Symbolic Significance

Beyond their biological importance, sandpipers hold symbolic meaning in various cultures. In Native American traditions, particularly among coastal tribes, the sandpiper is seen as a messenger between land and sea, embodying adaptability and keen perception. Its constant movement along the shoreline symbolizes vigilance and the ability to navigate life’s transitions.

In literature and poetry, the sandpiper often represents solitude and introspection. Mary Oliver’s poem "The Sandpiper" portrays the bird as focused and determined, scanning the world with intense concentration—a metaphor for mindfulness and presence in the moment.

In some Asian cultures, shorebirds like the common sandpiper appear in folklore as spirits of ancestors returning to visit the living, especially during seasonal migrations. These narratives reflect deep human connections to natural cycles and animal behavior.

Conservation Status and Threats

While some sandpiper species remain abundant, others face declining populations due to habitat degradation and climate change. The rufa subspecies of the red knot (Calidris canutus rufa), which overlaps ecologically with many sandpipers, is listed as threatened under the U.S. Endangered Species Act. This highlights broader concerns for migratory shorebirds.

Key threats include:

- Loss of stopover habitats: Coastal development reduces access to critical feeding areas.

- Overharvesting of horseshoe crabs: Their eggs are a primary food source for migrating shorebirds in Delaware Bay.

- Climate change: Alters breeding phenology and increases nest predation in the Arctic.

- Plastic pollution: Mistaken for food, microplastics can accumulate in digestive tracts.

Organizations like the Western Hemisphere Shorebird Reserve Network (WHSRN) and BirdLife International work to protect key sites and promote international cooperation. Citizen science initiatives such as the International Shorebird Survey encourage public participation in monitoring efforts.

How to Observe Sandpipers Responsibly

Birdwatching sandpipers can be a rewarding experience, but it requires ethical practices to minimize disturbance. Here are practical tips:

- Maintain distance: Use optical equipment instead of approaching closely.

- Stay on designated paths: Avoid trampling sensitive habitats like dunes or mudflats.

- Keep dogs leashed: Uncontrolled pets can stress or chase birds.

- Visit during optimal times: Early morning or late afternoon offers better light and higher bird activity.

- Report sightings: Contribute to databases like eBird to support scientific research.

Local Audubon chapters and national wildlife refuges often host guided walks led by experienced naturalists, providing educational opportunities for beginners.

Common Misconceptions About Sandpipers

Several myths persist about these birds. One common misconception is that all small shorebirds are sandpipers. In reality, plovers and snipes may look similar but differ in structure and behavior. Plovers, for instance, have shorter bills and use a 'look-run-peck' feeding style rather than probing.

Another misunderstanding is that sandpipers are exclusively coastal. While many are, species like the spotted sandpiper regularly breed near freshwater lakes and streams far from the ocean.

Lastly, people often assume that flocking birds are safe from extinction risks. However, even abundant species can decline rapidly if key habitats are lost—highlighting the need for proactive conservation.

Frequently Asked Questions

- What does a sandpiper bird look like?

- Sandpipers are generally small to medium-sized with long legs, slender bills, and mottled brown or gray plumage. They often have a quick, bobbing gait and are seen running along shorelines.

- Where do sandpipers go in the winter?

- Most sandpipers migrate to warmer regions. North American species typically winter along the southern U.S., Mexico, Central, and South America, while Eurasian species head to Africa, South Asia, and Australia.

- How can I tell different sandpiper species apart?

- Focus on bill length and shape, leg color, plumage details, and behavior. Field guides and birding apps can aid identification, especially during migration when multiple species overlap.

- Are sandpipers endangered?

- Some species are threatened due to habitat loss and climate change, though others remain common. Conservation status varies by species and region, so checking local and international listings is recommended.

- Can sandpipers fly long distances?

- Yes, many sandpipers are exceptional migrants. Some undertake nonstop flights of over 3,000 miles, fueled by fat reserves built up at stopover sites.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4