Bird flu, also known as avian influenza, is a viral infection that primarily affects birds but can occasionally spread to humans and other animals. This highly contagious disease is caused by strains of the influenza A virus, with H5N1 being one of the most well-known and concerning subtypes due to its high mortality rate in birds and potential for human transmission. Understanding what is bird flu and how it spreads is essential for public health, poultry farmers, wildlife biologists, and birdwatchers alike.

What Is Bird Flu: A Biological Overview

The term 'what is bird flu' refers to infections caused by avian influenza viruses that naturally occur among wild aquatic birds such as ducks, gulls, and shorebirds. These species often carry the virus without showing symptoms, acting as reservoirs. However, when transmitted to domestic poultry like chickens and turkeys, the disease can become highly pathogenic, leading to rapid outbreaks and massive die-offs. The virus belongs to the Orthomyxoviridae family and is classified based on two surface proteins: hemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N). There are 18 known H subtypes and 11 N subtypes, resulting in numerous combinations such as H5N1, H7N9, and H9N2.

Highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) strains cause severe illness and death in birds, while low pathogenic (LPAI) forms may only result in mild respiratory issues or reduced egg production. Most human cases have been linked to direct contact with infected birds or contaminated environments, especially in rural areas where backyard farming is common. Although sustained human-to-human transmission remains rare, scientists closely monitor mutations that could enable easier spread among people—a scenario that raises pandemic concerns.

Historical Outbreaks and Global Spread

The first major recognition of bird flu occurred in Italy in 1878, though it wasn't until the late 20th century that modern virology identified the causative agent. One of the most significant milestones in understanding what is bird flu came in 1997 during an outbreak in Hong Kong, where the H5N1 strain infected 18 people, killing six. This marked the first time this subtype was found to cross from birds to humans, prompting global alarm and swift culling of poultry populations.

Since then, multiple waves of H5N1 have swept across Asia, Europe, Africa, and more recently, North and South America. In 2022, the United States experienced its worst-ever bird flu outbreak, affecting over 58 million birds across 47 states. Wild migratory birds played a crucial role in spreading the virus across continents, highlighting the interconnectedness of ecosystems and the challenges in containment. More recently, in early 2024, new variants of H5N1 were detected in dairy cattle in the U.S., raising questions about cross-species transmission and food safety protocols.

How Does Bird Flu Spread?

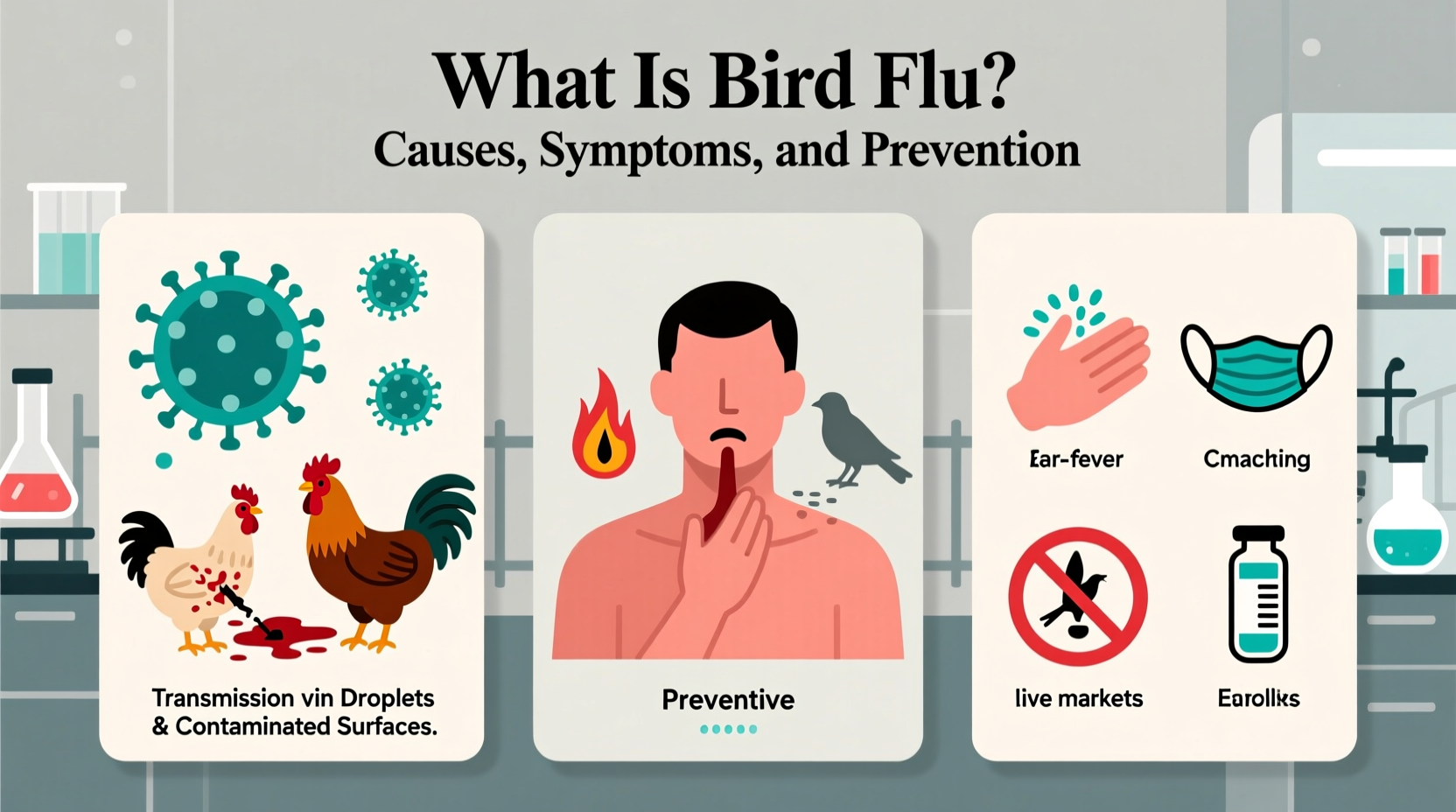

Bird flu spreads through several mechanisms, primarily via direct contact with infected birds or their bodily fluids—such as saliva, nasal secretions, and feces. Contaminated surfaces, equipment, feed, water, and even clothing can serve as fomites (objects that carry infection). Airborne transmission over short distances within enclosed spaces like barns is also possible.

Migratory birds are key vectors in the global dissemination of avian influenza. As these birds travel along flyways—established migration routes—they can introduce the virus into new regions. For example, the Mississippi Flyway and the Pacific Flyway in North America have seen increased detections of HPAI in recent years. Climate change and habitat disruption may be altering migration patterns, potentially increasing exposure risks to both wild and domestic bird populations.

In addition to natural spread, international trade in live birds and poultry products has contributed to regional outbreaks. Poor biosecurity practices on farms, especially small-scale or backyard operations, increase vulnerability. Workers moving between farms without proper sanitation procedures can inadvertently transport the virus.

Symptoms in Birds and Humans

In birds, signs of bird flu vary depending on the strain and species. Highly pathogenic strains may cause sudden death without prior symptoms. Other clinical signs include:

- Swelling of the head, eyelids, comb, wattles, and legs

- Purple discoloration of wattles and combs

- Respiratory distress (coughing, sneezing)

- Decreased food and water intake

- Drop in egg production or soft-shelled eggs

- Neurological signs such as tremors or lack of coordination

In humans, symptoms typically appear within 2–8 days after exposure and resemble severe influenza. Common manifestations include:

- Fever and chills

- Cough and sore throat

- Muscle aches and fatigue

- Headache

- Shortness of breath or pneumonia (in severe cases)

Rare complications can include acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), multi-organ failure, and death. Case fatality rates for H5N1 in humans have historically exceeded 50%, although actual numbers are low due to limited human infections.

Prevention and Control Measures

Preventing the spread of bird flu requires coordinated efforts at local, national, and international levels. Key strategies include:

- Biosecurity on Farms: Limiting access to poultry houses, using disinfectant footbaths, wearing protective clothing, and avoiding sharing equipment between farms.

- Surveillance Programs: Regular testing of wild bird populations and domestic flocks helps detect outbreaks early.

- Culling Infected Flocks: Rapid depopulation of infected or exposed birds reduces transmission risk.

- Vaccination (where applicable): While vaccines exist for certain strains, they are not universally used due to challenges in distinguishing vaccinated from infected birds (DIVA principle).

- Public Awareness: Educating communities about safe handling of poultry and reporting sick or dead birds.

For individuals who keep backyard chickens or engage in birdwatching, minimizing contact with wild birds and practicing good hygiene (e.g., handwashing after handling birds) are essential precautions.

Impact on Wildlife and Conservation

Bird flu poses a growing threat to biodiversity. In 2023, mass mortality events were reported in seabird colonies across the UK, Canada, and South Africa. Species such as gannets, puffins, and albatrosses—many already endangered—have suffered devastating losses. Scientists warn that repeated outbreaks could disrupt breeding cycles and lead to long-term population declines.

Conservationists are now integrating disease monitoring into wildlife management plans. Some organizations recommend temporarily closing visitor sites near nesting colonies during peak outbreak seasons to reduce human-assisted transmission.

| Strain | Pathogenicity | Primary Hosts | Human Cases Reported? |

|---|---|---|---|

| H5N1 | High | Wild waterfowl, poultry | Yes (rare) |

| H7N9 | High | Poultry (especially live markets) | Yes (moderate) |

| H9N2 | Low | Poultry | Occasionally |

| H5N8 | High | Wild birds, poultry | No |

Myths and Misconceptions About Bird Flu

Several misconceptions persist about what is bird flu and how dangerous it is to humans:

- Myth: Eating properly cooked poultry or eggs can give you bird flu.

Fact: The virus is destroyed at cooking temperatures above 70°C (158°F). No human cases have been linked to consumption of well-cooked food. - Myth: All bird deaths are due to bird flu.

Fact: Many factors—including poisoning, starvation, and other diseases—can kill birds. Laboratory testing is required for confirmation. - Myth: Only chickens get bird flu.

Fact: Over 100 bird species have tested positive, including raptors, songbirds, and waterfowl. - Myth: There’s nothing I can do if I see a dead bird.

Fact: Reporting dead wild birds to local authorities helps track outbreaks and initiate response measures.

What Birdwatchers Should Know

For bird enthusiasts, staying informed about current bird flu activity in your region is critical. Check with state wildlife agencies or organizations like the U.S. Geological Survey’s National Wildlife Health Center for real-time updates. Avoid touching sick or dead birds; use binoculars instead of approaching closely. Clean bird feeders regularly with a 10% bleach solution, especially during spring and fall migration periods when virus prevalence increases.

Some areas may issue advisories to remove bird feeders temporarily during active outbreaks to prevent congregation of birds, which can facilitate transmission. Always wash hands after outdoor activities involving birds.

Future Outlook and Research Directions

Ongoing research focuses on improving diagnostics, developing universal avian flu vaccines, and enhancing surveillance using genomic sequencing. Scientists are also studying how climate change, land use, and agricultural intensification influence the emergence and spread of avian influenza. International cooperation through bodies like the World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH) and the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) remains vital for early warning systems and resource sharing.

As global populations grow and demand for poultry increases, managing the interface between wild birds, domestic animals, and humans will be crucial in preventing future pandemics. Public engagement, scientific innovation, and policy integration must work together to address this complex zoonotic challenge.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- Can humans catch bird flu from watching birds?

No, casual observation of birds does not pose a risk. Transmission requires close contact with infected birds or contaminated materials. - Is it safe to eat chicken and eggs during a bird flu outbreak?

Yes, as long as they are properly handled and thoroughly cooked. The virus is killed by heat. - Are pet birds at risk?

Indoor pet birds have low risk, but outdoor aviaries should follow strict biosecurity measures during outbreaks. - Has bird flu been found in mammals?

Yes, sporadic cases have occurred in foxes, seals, and minks. Recently, infections in dairy cows raised new concerns about mammalian adaptation. - How can I report a sick or dead bird?

Contact your local wildlife agency or veterinarian. In the U.S., visit the USGS National Wildlife Health Center website for guidance.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4