Bird poop is commonly referred to as guano, a term that specifically describes the accumulated excrement of birds, particularly seabirds such as gulls, cormorants, and boobies. While "bird droppings" or "bird poop" are everyday terms used by the general public, guano is the scientific and historical designation most often encountered in ecological, agricultural, and ornithological contexts. This distinction is important for those researching bird behavior, soil enrichment, or even pest control around homes and urban spaces. Understanding what bird poop is calledâguanoânot only satisfies casual curiosity but also opens the door to deeper insights into its biological composition, cultural significance, and practical implications for gardeners, farmers, and wildlife enthusiasts alike.

The Biological Composition of Bird Poop: Why Birds Donât Urinate Like Mammals

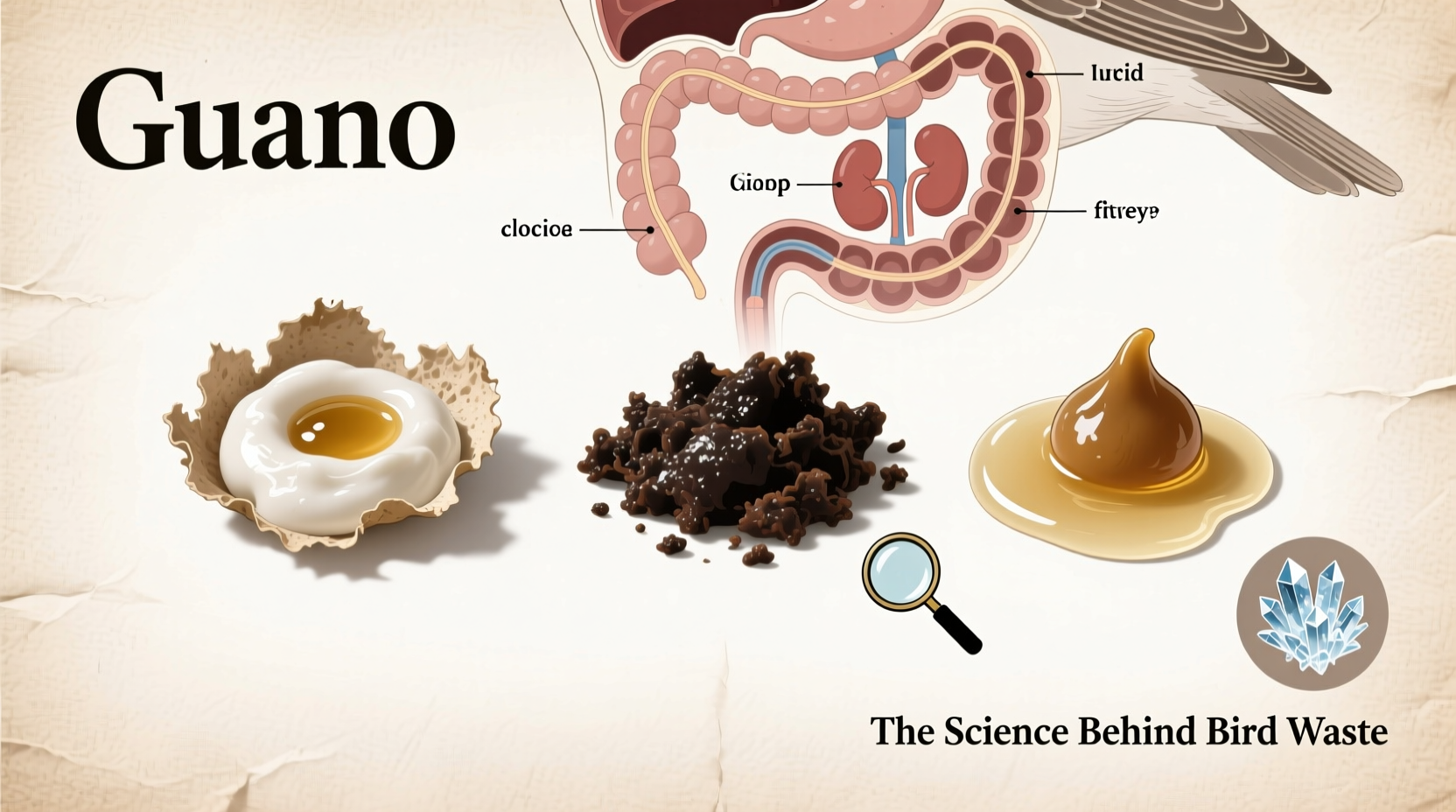

One of the most fascinating aspects of avian biology is how birds eliminate waste. Unlike mammals, which produce urine and feces separately, birds excrete both liquid and solid waste through a single opening called the cloaca. As a result, what we recognize as bird poop is actually a combination of fecal matter and uric acidâa white, paste-like substance that replaces urea in birdsâ waste system.

\p>Uric acid is less toxic and requires less water to expel than urea, making it an evolutionary adaptation ideal for animals that need to minimize weight during flight. This explains why bird droppings appear white or chalky on one end (the uric acid) and darker on the other (the digested food remnants). The high nitrogen and phosphate content in guano makes it exceptionally rich in nutrients, historically prized as a natural fertilizer.A Historical Perspective: The Global Impact of Guano Trade

The term guano originates from the Quechua word "wanu," used by Indigenous peoples of the Andes long before European contact. For centuries, Andean civilizations like the Inca collected seabird guano from coastal islands to enrich their crops, recognizing its power to boost agricultural yields in nutrient-poor soils.

This knowledge eventually reached Europe and North America in the 19th century, sparking what historians call the "Guano Age." Between the 1840s and 1880s, guano became so valuable that it triggered international competition, military expeditions, and even wars. The Chincha Islands War (1865â1866) between Spain and a Peruvian-Chilean alliance was partly fueled by control over major guano deposits.

In the United States, the Guano Islands Act of 1856 allowed American citizens to claim uninhabited islands containing guano deposits anywhere in the world. Under this law, over 100 islands were claimed across the Pacific and Caribbean, many of which remain U.S. territories today. This legislation underscores how economically significant bird poopâguanoâwas considered during the era of industrializing agriculture.

Ecological Importance of Guano in Natural Ecosystems

Beyond its use as fertilizer, guano plays a vital role in sustaining fragile island and marine ecosystems. Seabird colonies on remote atolls deposit massive quantities of guano over time, which slowly breaks down and leaches into surrounding waters. This process fertilizes coral reefs and stimulates plankton growth, forming the base of complex food webs.

Caves inhabited by large populations of bats and certain bird species, such as oilbirds or swiftlets, accumulate deep layers of guano over centuries. These deposits support unique microorganisms and invertebrates found nowhere else. Some cave ecosystems are entirely dependent on guano as their primary energy source.

However, excessive accumulation of guano can also lead to environmental challenges. High concentrations of nitrogen and ammonia may alter soil pH, inhibit plant growth, or contaminate freshwater sources. In areas with dense bird populations near human settlements, unmanaged guano buildup poses sanitation and health risks.

Health Risks Associated with Bird Droppings

While guano has undeniable benefits, direct exposure to fresh or dried bird droppings carries potential health hazards. One of the most well-documented dangers is histoplasmosis, a respiratory disease caused by inhaling spores of the fungus Histoplasma capsulatum, which thrives in nitrogen-rich environments like accumulated bird or bat droppings.

This condition primarily affects individuals with weakened immune systems but can impact anyone exposed to disturbed guano dust, especially during cleaning operations in attics, barns, or abandoned buildings. Another concern is cryptococcosis, linked to pigeon droppings, and psittacosis, a bacterial infection sometimes transmitted via inhalation of dried fecal particles from parrots and other psittacine birds.

To reduce risk:

- Wear N95 masks and gloves when cleaning large accumulations of bird droppings

- Mist dry guano with water before removal to prevent airborne particles

- Avoid sweeping or vacuuming dry deposits without proper protection

- Disinfect surfaces using EPA-approved cleaners effective against fungi and bacteria

Practical Uses of Guano Today

Modern organic farming continues to rely on processed seabird and bat guano as a sustainable source of nutrients. Available in powdered, granular, or liquid forms, guano-based fertilizers are marketed for their ability to improve soil structure, enhance microbial activity, and provide slow-release nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium.

Different types of guano offer varying nutrient profiles:

| Type of Guano | Primary Nutrient Profile | Common Use |

|---|---|---|

| Seabird Guano (Peruvian) | High in Nitrogen & Phosphorus | Leafy greens, flowering plants |

| Bat Guano (Cave-derived) | High in Phosphorus | Root development, blooming stages |

| Fruit Bat Guano | Moderate N-P-K, rich in micronutrients | General-purpose organic feed |

Gardeners appreciate guanoâs fast-acting nature compared to compost and its compatibility with hydroponic systems when properly diluted. However, sourcing matters: ethical and sustainable harvesting practices ensure that wild bird populations arenât disrupted for commercial gain.

Managing Bird Droppings Around Homes and Public Spaces

For property owners, dealing with bird poopâwhether on rooftops, statues, sidewalks, or vehiclesâis a common challenge. Pigeons, starlings, and gulls are frequent offenders in urban environments. Over time, acidic components in droppings can erode paint, corrode metal, and stain masonry.

Effective management strategies include:

- Exclusion: Install bird netting, spikes, or electric tracks to deter roosting on ledges and beams.

- Repellents: Use visual deterrents like reflective tape or predator decoys; avoid sticky gels that may trap small animals.

- Regular Cleaning: Power washing with mild detergent helps remove buildup safely. Always follow safety protocols to avoid pathogen exposure.

- Landscape Design: Avoid planting fruit-bearing trees near walkways if attracting frugivorous birds leads to excessive droppings.

Cultural Symbolism and Superstitions About Bird Poop

Somewhat surprisingly, being hit by bird poop carries symbolic meaning in various culturesâoften interpreted as good luck. In several European and Asian traditions, it's believed that if a bird defecates on you or your belongings, fortune is on the horizon. The rarity of the event contributes to its auspicious interpretationâmuch like finding a four-leaf clover.

Conversely, some maritime folklore warns sailors that bird droppings on deck could signal impending storms or bad omens, possibly due to increased bird activity before weather changes. In modern pop culture, getting âbombedâ by a bird is frequently played for comedic effect in films and TV shows, reinforcing its status as a quirky, if unpleasant, random occurrence.

How to Identify Bird Poop Species-Specifically

For birdwatchers and researchers, analyzing droppings can help identify species presence, diet, and health. General characteristics include:

- Pigeon/Columbidae: Large, grayish droppings with prominent white urate cap; often found in clusters under roosts.

- Raptors: Long, tubular white droppings (mostly uric acid), sometimes with bone fragments or feathers visible.

- Waterfowl: Soft, greenish-brown due to aquatic vegetation; more fluid consistency.

- Passerines (songbirds): Small, round dots with minimal white; vary in color based on diet (berries = reddish stains).

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- What is the correct term for bird poop?

- The scientific and historical term for bird poop is guano, especially when referring to accumulated excrement from seabirds or bats.

- Is bird poop harmful to humans?

- Fresh droppings pose minimal risk, but dried guano can harbor fungi like Histoplasma capsulatum, which causes respiratory illness when inhaled. Proper protective equipment is essential during cleanup.

- Can I use bird droppings as fertilizer in my garden?

- Yes, but only after proper processing. Raw bird poop is too concentrated and may burn plants or introduce pathogens. Commercially available guano fertilizers are sterilized and balanced for safe use.

- Why is bird poop white?

- The white portion is uric acid, the birdâs equivalent of urine. Birds excrete nitrogenous waste in this semi-solid form to conserve water and reduce body weight for flight.

- Are there legal restrictions on collecting bird guano?

- In many countries, including the U.S., disturbing active bird nests or collecting guano from protected species or conservation areas requires permits. Always check local wildlife regulations before harvesting.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4