Birds are not mammals. This is a common point of confusion, but the biological distinction is clear: birds are warm-blooded vertebrates that lay hard-shelled eggs, possess feathers, and lack mammary glands, which definitively separates them from mammals. While both birds and mammals are endothermic (warm-blooded) and have high metabolic rates, their evolutionary paths, anatomical features, and reproductive strategies place them in entirely different classes of the animal kingdom. A key natural longtail keyword variant that reflects this inquiry is 'why are birds not considered mammals despite being warm-blooded.'

Biological Classification: Where Birds Fit in the Animal Kingdom

To understand why birds aren't mammals, it’s essential to explore how scientists classify animals. The animal kingdom is divided into phyla, classes, orders, families, genera, and species. Birds belong to the class Aves, while mammals are classified under Mammalia. These two classes fall under the same phylum—Chordata—because they share a backbone, but that’s where most similarities end.

One of the defining traits of mammals is the presence of mammary glands, which produce milk to nourish their young. Birds do not have these glands and instead feed their offspring through regurgitation or by providing pre-chewed food. Additionally, mammals typically give birth to live young (with rare exceptions like the platypus), whereas all birds reproduce by laying eggs with calcified shells.

Anatomical Differences Between Birds and Mammals

The physical differences between birds and mammals go far beyond reproduction. Let’s examine some of the most significant distinctions:

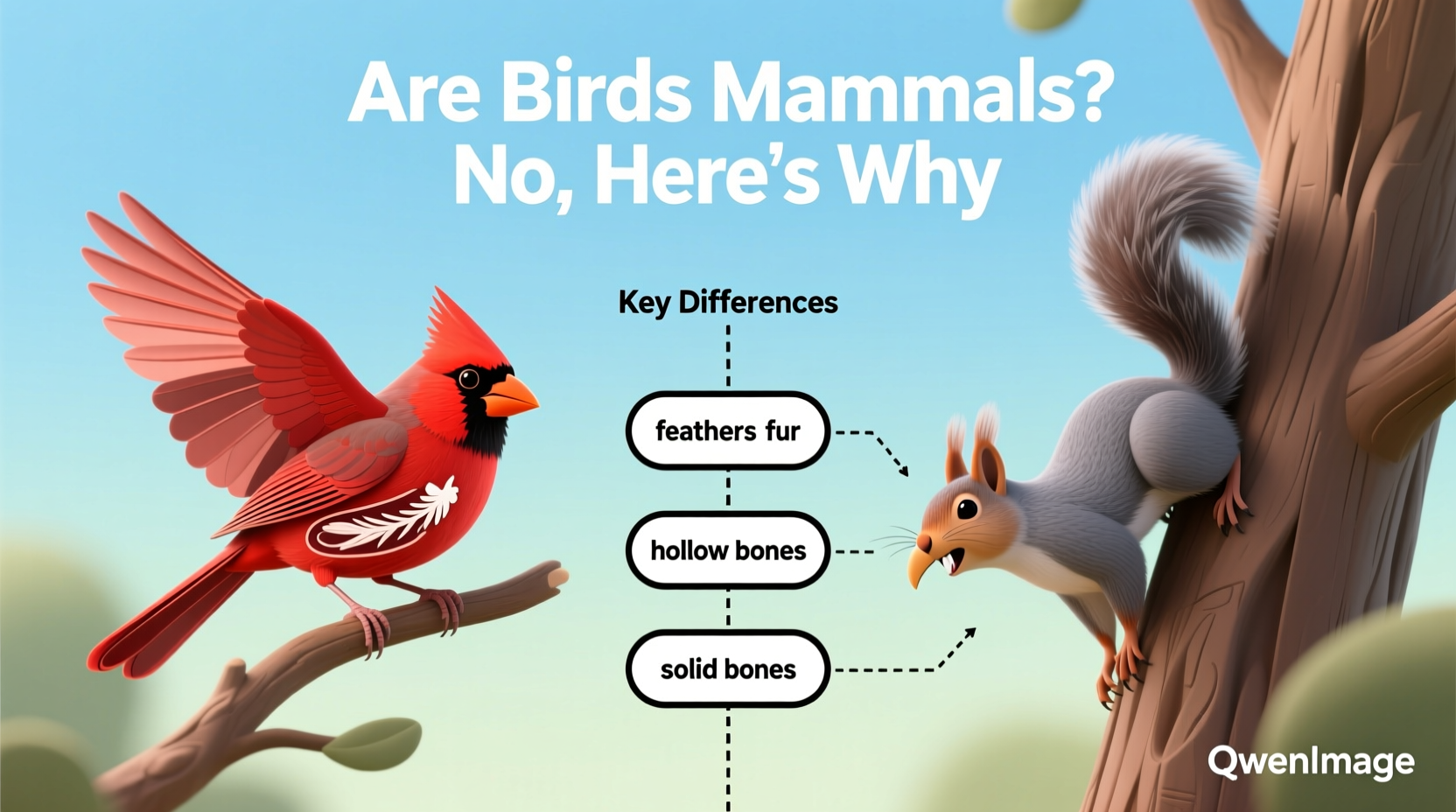

- Feathers vs. Hair/Fur: Feathers are unique to birds and serve multiple functions including flight, insulation, and display. Mammals, on the other hand, have hair or fur as their primary integumentary feature.

- Skeleton and Flight Adaptations: Bird skeletons are lightweight and fused in key areas (such as the pygostyle and keeled sternum) to support flight. Most mammals have heavier, more flexible skeletons adapted for walking, running, swimming, or climbing.

- Beaks vs. Teeth: Birds lack teeth and instead have beaks adapted to their diet—whether tearing flesh, cracking seeds, or sipping nectar. Mammals almost universally have teeth suited to their dietary niche.

- Respiratory System: Birds have a highly efficient one-way airflow respiratory system involving air sacs, allowing continuous oxygen uptake during both inhalation and exhalation. Mammals use a tidal breathing system where air moves in and out of the lungs similarly to a bellows.

Evolutionary Origins: How Birds Diverged from Other Vertebrates

Fossil evidence shows that birds evolved from theropod dinosaurs during the Mesozoic Era, approximately 150 million years ago. The discovery of Archaeopteryx in the 19th century provided crucial insight into this transition, showing a creature with both reptilian (teeth, long bony tail) and avian (feathers, wings) characteristics.

This dinosaur origin sets birds apart from mammals, which evolved from synapsid reptiles much earlier. Though both lineages survived the Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction event 66 million years ago, they followed vastly different evolutionary trajectories. Modern birds are now considered the only living descendants of dinosaurs, a fact that underscores their uniqueness among vertebrates.

Warm-Bloodedness: A Shared Trait with Key Differences

Both birds and mammals are endothermic, meaning they generate internal heat to maintain a constant body temperature. However, birds generally have higher body temperatures—often ranging from 104°F to 110°F (40°C to 43°C)—compared to mammals, which average around 98.6°F (37°C).

Birds also exhibit greater metabolic efficiency per unit of body mass, especially during flight. This elevated metabolism requires frequent feeding and a specialized digestive system, including a crop and gizzard in many species. Mammals, by contrast, rely on chewing and complex stomachs (in ruminants) or long intestines to process food.

Reproductive Strategies: Eggs vs. Live Birth

Reproduction is one of the most definitive ways to distinguish birds from mammals. All known bird species lay amniotic eggs with hard calcium carbonate shells. These eggs are incubated externally, often by one or both parents, until hatching.

In contrast, the vast majority of mammals are viviparous, giving birth to live young after internal gestation. Only monotremes—such as the platypus and echidna—lay eggs, but even then, they produce leathery eggs (not calcified) and nurse their young with milk, confirming their status as mammals.

Another critical difference is parental care. While both birds and mammals often provide extensive postnatal care, birds do so without lactation. Instead, altricial chicks (born helpless) are fed directly by parents, while precocial chicks (born mobile) can follow adults shortly after hatching.

Behavioral and Cognitive Complexity in Birds

Despite lacking mammalian brains, many bird species exhibit remarkable intelligence. Corvids (crows, ravens, jays) and parrots are known for problem-solving abilities, tool use, and even self-recognition in mirror tests—traits once thought exclusive to primates.

Birdsong, particularly in songbirds (order Passeriformes), involves complex neural circuitry and learning processes akin to human language acquisition. This behavioral sophistication challenges outdated notions that non-mammals are cognitively inferior.

Cultural and Symbolic Significance of Birds Across Civilizations

Beyond biology, birds hold deep symbolic meaning in cultures worldwide. In ancient Egypt, the Bennu bird (a precursor to the phoenix) symbolized rebirth and immortality. Native American traditions often view eagles as messengers between humans and the divine. In Christianity, the dove represents peace and the Holy Spirit.

In literature and art, birds frequently embody freedom, transcendence, and the soul’s journey. The migration of birds has inspired metaphors for seasonal change, longing, and spiritual pilgrimage. Understanding these cultural layers enriches our appreciation of birds beyond mere classification.

Practical Guide to Observing Birds: Tips for Aspiring Ornithologists

If you're interested in learning more about birds firsthand, birdwatching (or birding) is an accessible and rewarding hobby. Here are practical tips to get started:

- Get a Field Guide or App: Use resources like the Sibley Guide to Birds or apps such as Merlin Bird ID to identify species by appearance, call, and habitat.

- Invest in Binoculars: A good pair with 8x42 magnification offers a balance of field of view and detail.

- Visit Local Hotspots: Parks, wetlands, coastlines, and forests attract diverse species. Check eBird.org for real-time sightings near you.

- Learn Bird Calls: Many birds are heard before they’re seen. Practice identifying common songs and alarm calls.

- Keep a Journal: Record species, behaviors, weather, and location to track patterns over time.

Timing matters: early morning hours (dawn to mid-morning) are optimal for bird activity. Seasons also influence what you’ll see—spring brings migratory songbirds, while winter may reveal raptors and waterfowl.

Common Misconceptions About Birds and Mammals

Several myths persist about the relationship between birds and mammals. One widespread misconception is that because bats fly and some birds don’t (e.g., ostriches, penguins), flight defines the difference. But bats are mammals due to hair, live birth, and milk production—flight evolved independently in birds and bats (an example of convergent evolution).

Another myth is that all egg-laying animals are 'primitive.' In reality, avian reproduction is highly advanced, with internal fertilization, complex embryonic development, and precise hormonal regulation.

Some people believe that birds have 'simple' brains due to size, but neuron density in bird brains—especially in the forebrain—is comparable to primates, enabling sophisticated cognition.

Regional Variations in Bird Diversity and Observation Opportunities

Bird diversity varies dramatically by region. Tropical zones like the Amazon Basin and Southeast Asia host the highest number of species due to stable climates and rich ecosystems. Temperate regions experience seasonal fluctuations, with summer breeding residents and winter migrants.

In North America, the National Audubon Society and Cornell Lab of Ornithology organize events like the Christmas Bird Count and Global Big Day to engage citizen scientists. Europe has similar initiatives through organizations like BirdLife International.

If you live in urban areas, don’t assume there are no birds to observe. Cities support pigeons, sparrows, starlings, and increasingly, peregrine falcons nesting on skyscrapers. Green roofs, parks, and backyard feeders enhance urban biodiversity.

| Feature | Birds (Class Aves) | Mammals (Class Mammalia) |

|---|---|---|

| Body Covering | Feathers | Hair or Fur |

| Reproduction | Egg-laying (oviparous) | Mostly live birth (viviparous) |

| Milk Production | No mammary glands | Yes, mammary glands present |

| Teeth | None (beak instead) | Present (varied types) |

| Skeleton | Lightweight, fused bones, air-filled | Dense, not pneumatized |

| Respiration | One-way airflow with air sacs | Tidal flow (in-and-out) |

How to Verify Information About Bird Identification and Biology

With so much misinformation online, it’s important to consult authoritative sources when studying birds. Reliable institutions include:

- Cornell Lab of Ornithology (birds.cornell.edu)

- National Audubon Society (audubon.org)

- Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History

- Peer-reviewed journals like The Auk and The Condor

When identifying a bird, cross-reference multiple sources and consider geographical range, season, and behavior. Apps powered by AI can assist, but should not replace expert verification.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Are there any mammals that lay eggs?

A: Yes, the platypus and echidna (also called spiny anteaters) are egg-laying mammals known as monotremes. Despite laying eggs, they are classified as mammals because they produce milk and have hair.

Q: Why do people think birds might be mammals?

A: Because birds and mammals are both warm-blooded, breathe air, and care for their young, they appear similar at first glance. However, fundamental differences in anatomy, reproduction, and genetics place them in separate classes.

Q: Can birds and mammals interbreed?

A: No. Birds and mammals diverged evolutionarily over 300 million years ago and have incompatible genetics, reproductive systems, and chromosome structures.

Q: Do all birds fly?

A: No. Some birds, like ostriches, emus, cassowaries, and penguins, are flightless. However, they still possess feathers and other avian characteristics.

Q: What is the closest living relative to birds?

A: Crocodilians (crocodiles and alligators) are the closest living relatives to birds. Both share a common ancestor among archosaur reptiles from the Triassic period.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4