Yes, birds do have bone marrow—a crucial component of their skeletal and circulatory systems. Like mammals, avian species rely on bone marrow located within the cavities of their bones to produce blood cells through a process called hematopoiesis. This vital biological function ensures that birds maintain healthy levels of red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets necessary for oxygen transport, immune defense, and clotting. A natural longtail keyword variant such as 'do birds have bone marrow like mammals' reflects a common inquiry rooted in comparative anatomy, and the answer is both scientifically significant and evolutionarily insightful.

The Biological Role of Bone Marrow in Birds

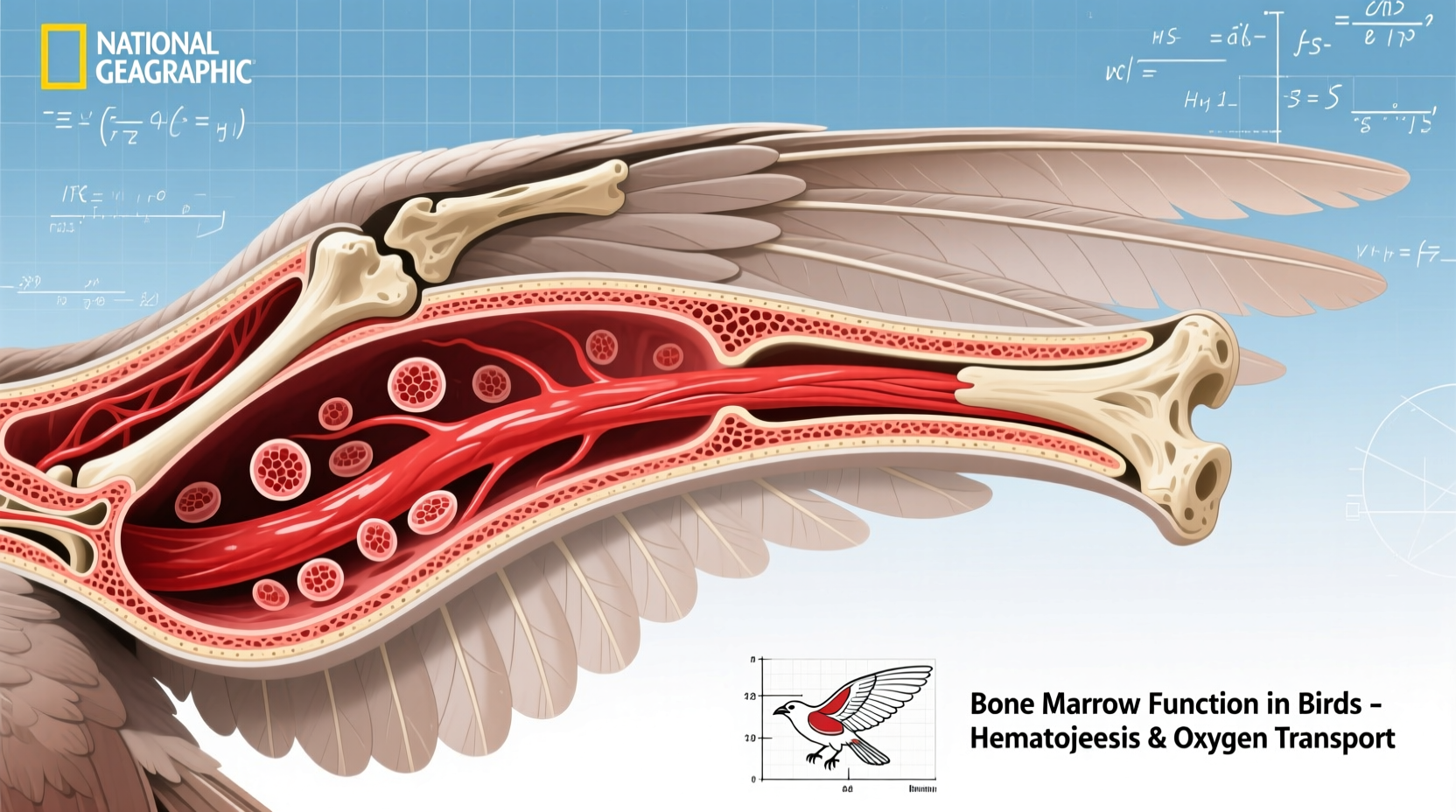

Bone marrow in birds serves the same fundamental purpose as it does in mammals: it is the primary site of hematopoiesis, the formation of blood cellular components. In adult birds, red bone marrow—responsible for producing all types of blood cells—is predominantly found in the medullary cavities of certain bones, including the femur, humerus, sternum, and pelvic girdle. Unlike many mammals, where red marrow may be more widely distributed in youth and later replaced by yellow (fatty) marrow, birds retain functional red marrow in key weight-bearing and large bones throughout life.

This adaptation supports their high metabolic rates and energy demands associated with flight. The continuous production of erythrocytes (red blood cells) is essential because birds have higher oxygen requirements than most terrestrial animals. Their respiratory and circulatory systems are highly efficient, and bone marrow plays a pivotal behind-the-scenes role in sustaining this performance.

Differences Between Avian and Mammalian Bone Marrow

While birds and mammals both possess bone marrow capable of hematopoiesis, there are notable anatomical and physiological distinctions. One major difference lies in bone structure. Bird bones are generally pneumatized—meaning they contain air sac extensions that reduce weight for flight. As a result, not all bones can house marrow. Only non-pneumatic or partially pneumatic bones serve as sites for active marrow development.

Additionally, birds lack a diaphyseal marrow cavity in many long bones due to pneumatization, so hematopoietic tissue tends to concentrate in specific regions. For example, the proximal ends of long bones and flat bones become primary centers of blood cell production. Another distinction is that birds have nucleated red blood cells, unlike mammals whose mature erythrocytes lose their nuclei. This means the maturation process within avian bone marrow differs slightly, requiring extended support for developing cells before release into circulation.

Developmental Changes in Avian Bone Marrow

In embryonic and juvenile birds, hematopoiesis begins in the yolk sac before transitioning to the liver and spleen, and eventually to the bone marrow—a sequence similar to that seen in mammals. By the time a bird reaches post-hatch maturity, bone marrow becomes the dominant site of blood cell formation.

The timing and location of this transition vary among species. In chickens (Gallus gallus domesticus), one of the most studied avian models, red marrow activity peaks during rapid growth phases and remains robust even in adulthood due to ongoing egg production in hens, which demands increased calcium and blood volume regulation.

Interestingly, female birds preparing for egg-laying cycles can develop temporary medullary bone—a specialized form of calcified tissue rich in calcium stores, formed under estrogen stimulation. While not hematopoietic itself, this tissue forms within marrow spaces and demonstrates the dynamic use of bone interiors beyond just blood cell production.

Medical and Veterinary Importance of Avian Bone Marrow

Understanding avian bone marrow is critical in veterinary medicine, particularly in diagnosing diseases such as leukosis, anemia, or infections like avian influenza that can suppress bone marrow function. Bone marrow aspiration—a diagnostic procedure involving the extraction of marrow from accessible bones like the humerus or tibiotarsus—is sometimes performed in larger birds such as raptors, waterfowl, or poultry to assess hematopoietic health.

Challenges in sampling arise due to small bone size in passerines (perching birds) and the risk of damaging delicate structures. Veterinarians must consider species-specific anatomy and sedation protocols when evaluating potential marrow disorders. Abnormalities in cell counts, morphology, or ratios of immature to mature cells can indicate underlying pathologies ranging from nutritional deficiencies to neoplasia.

Comparative Anatomy: Do All Birds Have the Same Marrow Distribution?

No, marrow distribution varies across bird species depending on size, flight capability, and metabolic needs. Flightless birds such as ostriches and emus exhibit broader distributions of red marrow, resembling mammalian patterns more closely due to less pneumatization. In contrast, highly aerial species like swifts and albatrosses show concentrated marrow in limited skeletal sites, reflecting evolutionary trade-offs between lightweight construction and physiological demand.

A study published in the Journal of Morphology (2018) analyzed marrow volume in 60 bird species and found a strong inverse correlation between degree of skeletal pneumatization and total marrow mass. This suggests that while all birds have functional bone marrow, the extent and localization are shaped by ecological and biomechanical pressures.

| Feature | Birds | Mammals |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Site of Hematopoiesis (Adult) | Red marrow in select bones (e.g., femur, sternum) | Red marrow in flat bones and metaphyses of long bones |

| Bone Pneumatization | Present in most species | Absent |

| Mature Red Blood Cells | Nucleated | Anucleate |

| Yellow Marrow Conversion | Limited; red marrow persists in key areas | Extensive conversion with age |

| Medullary Bone Formation | Yes, in reproductively active females | No equivalent structure |

Skeletal Adaptations and Marrow Space Constraints

The presence of air-filled bones in most birds imposes structural constraints on marrow volume. To compensate, birds have evolved enhanced efficiency in hematopoietic output per unit volume of marrow. Research indicates that avian stem cells in the marrow may divide more rapidly or respond more sensitively to hormonal signals like erythropoietin, ensuring adequate red blood cell production despite spatial limitations.

Moreover, some birds demonstrate extramedullary hematopoiesis—the production of blood cells outside the bone marrow—under stress conditions. The spleen and liver can resume hematopoietic roles during severe anemia or infection, providing a physiological backup system. This plasticity underscores the resilience of avian physiology and highlights how bone marrow, while central, is part of a broader network supporting blood homeostasis.

Observing Bone Marrow in Wild and Captive Birds: Practical Insights

For ornithologists and wildlife rehabilitators, indirect indicators of bone marrow health include feather quality, activity level, and mucous membrane color (a sign of anemia). Pale comb or wattles in poultry, for instance, may suggest poor erythrocyte production linked to marrow suppression.

In field studies, researchers analyzing bone composition often use micro-CT scanning or histological sections to examine marrow cavities without destructive sampling. These techniques help preserve specimens while yielding detailed data on marrow distribution and density—information valuable for conservation biology and paleornithology alike.

If you're involved in avian care, whether in a zoo, sanctuary, or backyard flock, monitoring diet is crucial. Nutrients such as iron, vitamin B12, folic acid, and copper are essential for effective hematopoiesis. Deficiencies can impair marrow function, leading to clinical signs like lethargy, weakness, or reduced reproductive success.

Common Misconceptions About Birds and Bone Marrow

One widespread misconception is that because bird bones are hollow, they cannot contain soft tissues like marrow. This is false. While many bones are pneumatized, they still contain internal struts and septa that separate air spaces from vascularized marrow compartments. The term “hollow” is misleading—it implies emptiness, but these bones are structurally complex and biologically active.

Another myth is that birds don’t need bone marrow because they’re so different from mammals. On the contrary, their fast-paced lifestyles make a reliable, high-output hematopoietic system even more essential. Without functional bone marrow, birds could not sustain the aerobic demands of sustained flight or thermoregulation in extreme environments.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Do all birds have bone marrow?

- Yes, all birds have bone marrow, though its distribution varies by species based on flight ability and skeletal structure.

- Can birds regenerate bone marrow after injury?

- Yes, birds possess regenerative capacity in hematopoietic tissues. Following mild marrow suppression, recovery typically occurs if the cause is removed and supportive care is provided.

- Is bird bone marrow edible or consumed by humans?

- In some cultures, marrow from large birds like ostriches is eaten, though it's far less common than mammalian marrow. It has a similar nutrient profile—rich in fats, proteins, and minerals.

- Do baby birds have more bone marrow than adults?

- Not necessarily more in volume, but juvenile birds often have wider distribution of hematopoietic tissue, which becomes more localized as they mature.

- How do scientists study bone marrow in wild birds?

- Non-invasive imaging (like CT scans), blood tests, and post-mortem histology are used. Live sampling is rare and reserved for medical or research purposes under ethical oversight.

In summary, the question 'do birds have bone marrow' can be definitively answered in the affirmative. Birds not only have bone marrow but depend on it critically for survival. Its structure and function reflect millions of years of evolutionary refinement, balancing the competing needs of lightness for flight and robustness for physiological endurance. Whether viewed through the lens of veterinary science, evolutionary biology, or ecological adaptation, avian bone marrow stands as a testament to nature’s ingenuity in solving complex biological challenges.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4