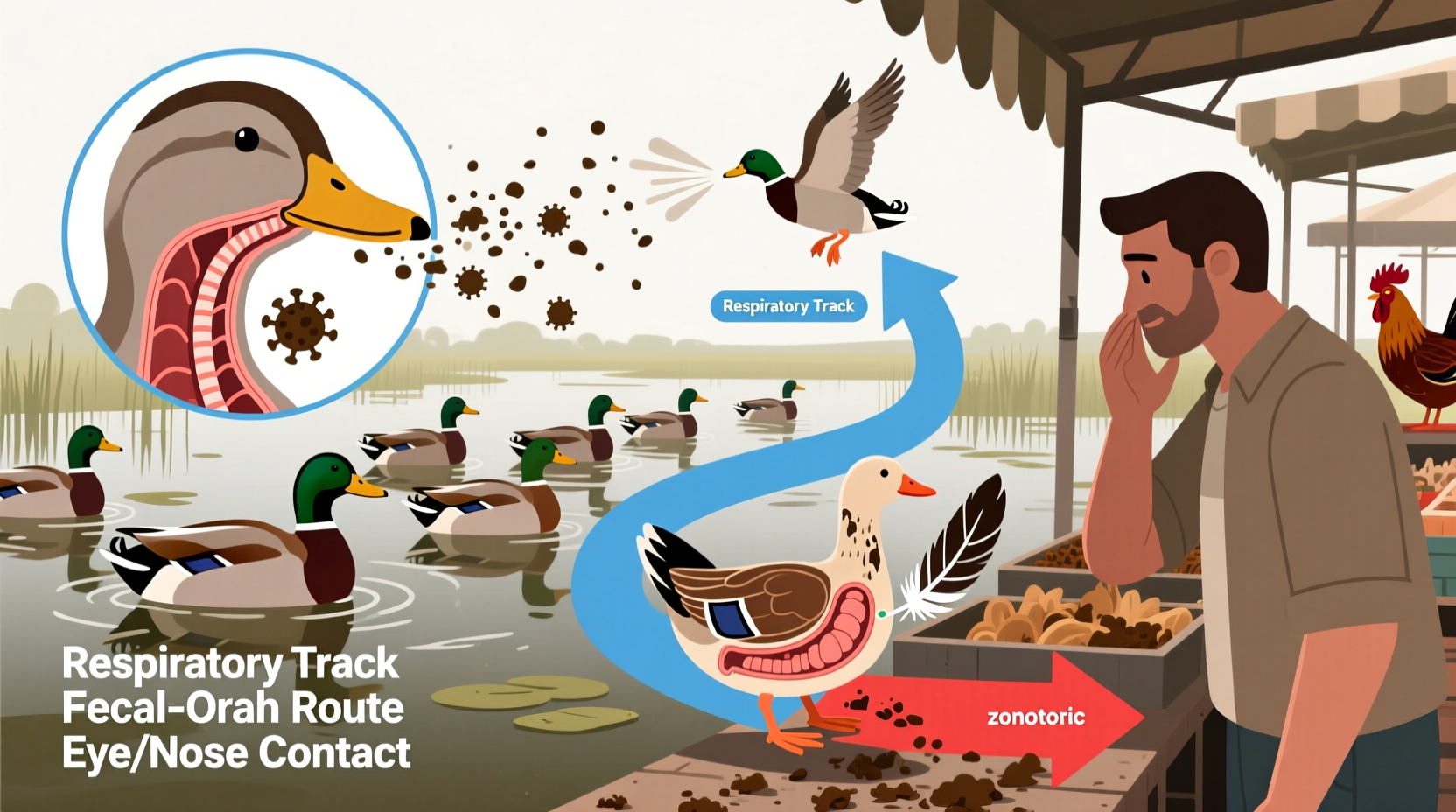

Bird flu, also known as avian influenza, primarily spreads through direct contact with infected birds or contaminated environments. One of the most common ways bird flu spreads is via respiratory secretions, saliva, and feces from infected poultry and wild birds. This natural transmission route allows the virus to move rapidly within flocks and across regions, especially during migratory seasons when wild waterfowl carry the virus over long distances. Understanding how bird flu spreads among bird populations—and how it can jump to humans—is essential for preventing outbreaks in both agriculture and public health settings.

What Is Bird Flu?

Bird flu refers to a group of influenza viruses that primarily infect birds. These viruses belong to the family Orthomyxoviridae and are classified based on two surface proteins: hemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N). There are numerous subtypes, but H5N1 and H7N9 are among the most concerning due to their high pathogenicity and potential to infect humans. While low-pathogenic strains may cause mild symptoms in birds, highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) can lead to rapid death in entire poultry flocks.

The virus naturally circulates in wild aquatic birds such as ducks, geese, and swans, which often show no signs of illness but can shed the virus in their droppings. This silent transmission plays a critical role in how bird flu spreads across continents, particularly along major migration flyways.

Primary Transmission Routes Among Birds

The spread of bird flu among avian species occurs through several interconnected pathways:

- Direct Contact: Physical interaction between healthy and infected birds—especially in crowded conditions like commercial poultry farms or live bird markets—facilitates rapid transmission.

- Fecal-Oral Route: Infected birds excrete the virus in large quantities through feces. Other birds become infected by ingesting contaminated water or feed.

- Aerosol Transmission: In enclosed spaces, the virus can spread through airborne particles containing respiratory secretions.

- Contaminated Surfaces: Equipment, clothing, cages, and transport vehicles can carry the virus from one location to another if not properly sanitized.

Wild birds, particularly migratory waterfowl, serve as reservoirs and vectors. They acquire the virus at breeding or wintering grounds and transmit it during stopovers at wetlands and lakes used by domestic birds. This interplay between wild and domestic populations significantly influences how bird flu spreads across rural and urban landscapes.

How Bird Flu Spreads to Humans

Human infections with avian influenza are rare but possible. Most cases occur after close and prolonged contact with infected birds or heavily contaminated environments. Key risk factors include:

- Killing, plucking, or preparing infected poultry for cooking

- Working in live bird markets or poultry farms experiencing an outbreak

- Exposure to bird droppings or bedding material from infected flocks

- Consuming undercooked poultry products (though proper cooking kills the virus)

It’s important to note that how bird flu spreads to humans does not typically involve sustained person-to-person transmission. Most human cases have been isolated, though there is ongoing concern that the virus could mutate to become more easily transmissible between people—a scenario that would pose a significant pandemic threat.

Global Patterns and Seasonal Influences

The geographic spread of bird flu follows seasonal bird migration patterns. In the Northern Hemisphere, outbreaks often peak between late fall and early spring when migratory birds travel southward. Countries along major flyways—including China, India, parts of Africa, Eastern Europe, and North America—experience recurring incursions of the virus.

For example, in 2022 and 2023, the United States saw its largest-ever recorded outbreak of HPAI H5N1, affecting over 58 million birds across 47 states. The timing coincided with autumn migration, confirming the link between wild bird movements and domestic poultry infections.

Climate change may also be influencing how bird flu spreads by altering migration routes, breeding cycles, and habitat availability. Warmer temperatures extend the survival time of the virus in the environment, increasing the window for transmission.

Role of Poultry Farming Practices

Intensive farming systems can amplify the risk of bird flu transmission. High-density housing, limited biosecurity measures, and frequent animal movement create ideal conditions for viral spread. Once introduced into a facility, the virus can infect thousands of birds within days.

Backyard flocks also contribute to transmission dynamics. Unlike commercial operations, many small-scale owners lack access to veterinary services or awareness of biosecurity protocols. Free-ranging chickens that come into contact with wild birds increase the likelihood of exposure.

To reduce risks, farmers should implement strict biosecurity practices such as:

- Limiting farm access to essential personnel only

- Using dedicated footwear and clothing for poultry areas

- Disinfecting equipment and vehicles before entry

- Isolating new birds before introducing them to existing flocks

- Providing covered feeding and watering systems to prevent contamination

Prevention and Surveillance Strategies

Preventing the spread of bird flu requires coordinated efforts at local, national, and international levels. Key components include:

| Strategy | Description | Effectiveness |

|---|---|---|

| Active Surveillance | Regular testing of wild and domestic birds in high-risk zones | High – enables early detection |

| Vaccination Programs | Used selectively in some countries to protect poultry | Moderate – reduces severity but doesn’t eliminate shedding |

| Culling Infected Flocks | Rapid depopulation to contain outbreaks | High – effective short-term control measure |

| Public Awareness Campaigns | Educating farmers and the public about risks and precautions | Variable – depends on outreach quality |

Organizations like the World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH), the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) collaborate to monitor global trends and support response efforts.

Common Misconceptions About How Bird Flu Spreads

Several myths persist about avian influenza transmission:

- Myth: Eating chicken or eggs can give you bird flu.

Fact: Properly cooked poultry and pasteurized egg products are safe. The virus is destroyed at temperatures above 70°C (158°F). - Myth: All bird species are equally likely to spread the virus.

Fact: Waterfowl are primary carriers; songbirds and raptors are less commonly involved. - Myth: Bird flu spreads easily from person to person.

Fact: Human-to-human transmission is extremely rare and not self-sustaining.

Regional Differences in Outbreak Management

Responses to bird flu vary widely depending on regional infrastructure and economic priorities. In high-income countries like the U.S. and those in the EU, rapid culling, movement restrictions, and compensation programs help limit spread. In contrast, resource-limited nations may delay reporting due to fears of trade restrictions, allowing undetected circulation.

In Asia, where live bird markets remain common, cultural preferences for fresh poultry complicate containment. Some governments have implemented market rest days and zoning regulations to reduce risk. However, enforcement varies, impacting how effectively bird flu spreads can be controlled.

What You Can Do as a Bird Watcher or Pet Owner

If you enjoy birdwatching or keep backyard poultry, you play a vital role in monitoring and preventing disease spread:

- Avoid touching sick or dead birds. Report them to local wildlife authorities.

- Do not handle birds without gloves and protective gear if necessary.

- Clean bird feeders and baths regularly using a 10% bleach solution.

- Keep pet birds indoors during known outbreaks.

- Wash hands thoroughly after outdoor activities involving birds.

Mobile apps and citizen science platforms like eBird and iNaturalist now allow users to report unusual bird deaths or behaviors, contributing valuable data to surveillance networks.

Future Outlook and Research Directions

Scientists are actively studying how bird flu spreads at the molecular level to develop better vaccines and antiviral treatments. Genomic sequencing helps track mutations that could enhance transmissibility or host range. Researchers are also exploring ecological interventions, such as modifying wetland use during peak migration, to reduce cross-species contact.

One emerging area focuses on predicting outbreaks using climate models and satellite tracking of bird migrations. By integrating environmental, virological, and behavioral data, experts hope to forecast hotspots before outbreaks occur—transforming reactive responses into proactive prevention.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Can humans get bird flu from watching wild birds?

- No, simply observing birds from a distance poses no risk. Infection requires direct contact with infected birds or their secretions.

- Is it safe to feed wild birds during a bird flu outbreak?

- It's advised to暂停 feeding during active outbreaks, as feeders can concentrate birds and facilitate disease transmission. Clean feeders weekly if used.

- Does bird flu affect all bird species equally?

- No. Chickens and turkeys are highly susceptible to severe disease, while many wild ducks carry the virus asymptomatically.

- How long can the bird flu virus survive in the environment?

- The virus can persist for days to weeks—longer in cold, moist conditions like ponds or barns.

- Are there vaccines for bird flu in humans?

- Limited stockpiles exist for certain strains (like H5N1), but they are not widely available and are intended for emergency use only.

Understanding how bird flu spreads is crucial for protecting both animal and human health. Through improved surveillance, responsible farming, and public education, we can reduce the impact of this dynamic and evolving disease.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4