Bird flu, also known as avian influenza, is highly contagious among birds—particularly in dense populations such as commercial poultry farms or migratory flocks. The most virulent strains, like H5N1, can spread rapidly through direct contact with infected birds, contaminated surfaces, or airborne particles in enclosed spaces. While human infections remain rare, the question of how contagious is bird flu depends heavily on the strain, host species, and environmental conditions. This article explores the biological mechanisms of transmission, cultural perceptions of avian disease, practical advice for birdwatchers and farmers, and steps to reduce risk during outbreaks.

Understanding Avian Influenza: Types and Transmission Pathways

Avian influenza viruses belong to the influenza A family and are categorized by surface proteins: hemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N). There are 18 H subtypes and 11 N subtypes, but only a few—including H5 and H7—are known to cause severe disease in birds and occasional spillover to mammals.

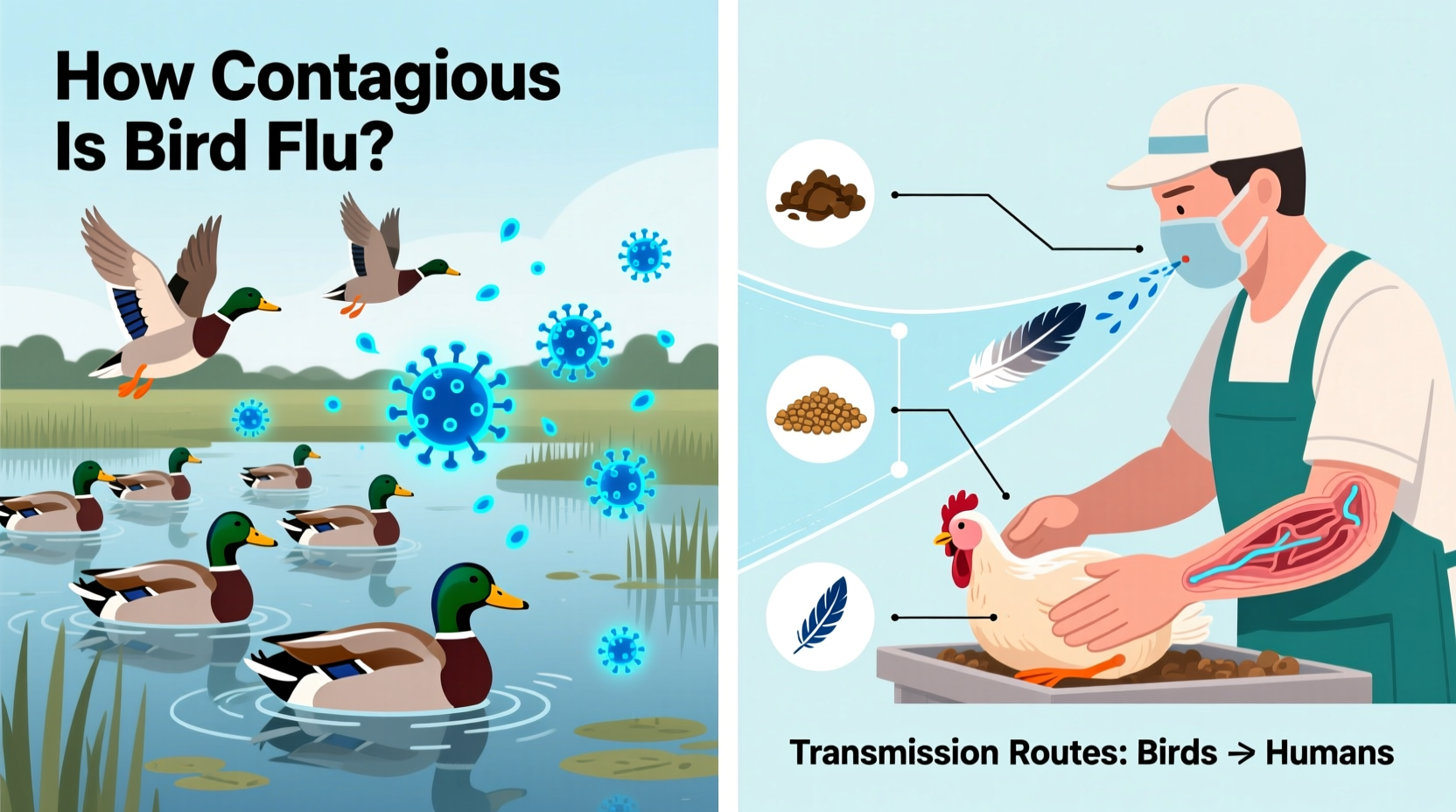

The virus spreads primarily through:

- Fecal-oral route: Infected birds shed the virus in droppings and saliva.

- Aerosol transmission: In confined spaces like barns, the virus can become airborne.

- Contaminated equipment: Shoes, clothing, cages, and vehicles can carry the virus between sites.

- Wild bird migration: Migratory waterfowl serve as natural reservoirs, spreading the virus across continents.

Highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI), such as H5N1, causes rapid mortality in domestic poultry and has led to mass culling events worldwide. Low pathogenic strains may circulate silently before mutating into more dangerous forms.

Human Risk: How Likely Are You to Catch Bird Flu?

Despite its high contagion among birds, bird flu does not easily transmit from birds to humans—or between people. Most human cases have occurred after prolonged, close contact with infected poultry, especially during slaughter or handling sick birds without protective gear.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), there have been fewer than 900 confirmed human cases of H5N1 since 2003, with a fatality rate exceeding 50%. However, this reflects severity rather than transmissibility. The limited number of cases suggests poor human-to-human spread under normal conditions.

Still, public health officials monitor outbreaks closely because influenza viruses can mutate. If H5N1 or another strain gains the ability to spread efficiently between humans, it could trigger a pandemic. That’s why understanding how contagious bird flu is in both animal and human contexts remains critical for global preparedness.

Global Outbreak Trends and Recent Surveillance Data

In recent years, particularly since 2020, HPAI H5N1 has re-emerged as a major threat to global bird populations. The 2021–2024 panzootic—the animal equivalent of a pandemic—has affected over 100 countries, leading to the death or culling of hundreds of millions of poultry.

Unusually, this strain has also infected a wide range of wild species, including eagles, foxes, seals, and even dairy cattle in the United States in 2024. In March 2024, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported the first U.S. case of H5N1 in a person linked to exposure to infected dairy cows—a rare event that raised concerns about potential mammalian adaptation.

Despite these developments, no sustained human-to-human transmission has been documented. Ongoing genomic sequencing shows that while the virus is evolving, it hasn’t acquired the mutations necessary for efficient airborne spread in humans.

Cultural and Symbolic Perceptions of Bird Flu

Birds have long symbolized freedom, spirituality, and divine messages across cultures—from the sacred ibis in ancient Egypt to the dove of peace in Judeo-Christian traditions. When diseases like bird flu threaten avian life, they disrupt not just ecosystems but also cultural narratives tied to birds.

In parts of Southeast Asia, where backyard poultry farming is common, bird flu outbreaks evoke fear beyond health risks—they represent economic loss, spiritual imbalance, and broken traditions. Rituals involving birds, such as releasing doves at weddings or feeding pigeons at temples, have been restricted during outbreaks, altering community practices.

Conversely, Western media often sensationalizes bird flu as a “doomsday virus,” amplifying anxiety despite low personal risk. This contrast highlights the need for science-based communication that respects cultural values while promoting accurate risk assessment.

Practical Guidance for Farmers and Poultry Workers

For those working with birds, reducing contagion risk requires strict biosecurity protocols. Here are key recommendations:

- Isolate new birds: Quarantine all incoming poultry for at least 30 days.

- Control access: Limit visitors to farms and require disinfection of footwear and tools.

- Monitor flock health: Report sudden deaths or respiratory symptoms immediately to veterinary authorities.

- Vaccinate when appropriate: Although vaccines exist, their use must be coordinated with surveillance to avoid masking infection.

- Dispose of carcasses safely: Use sealed containers and incineration or deep burial to prevent scavenger exposure.

In regions experiencing outbreaks, governments may impose movement restrictions on live birds. Staying informed through national agricultural departments or organizations like the OIE (World Organisation for Animal Health) is essential.

Tips for Birdwatchers and Outdoor Enthusiasts

Wildlife observers should take precautions during active bird flu seasons. While the risk to humans is minimal, responsible behavior protects both people and birds.

- Avoid contact with sick or dead birds: Do not touch or handle them. Report findings to local wildlife agencies.

- Use binoculars instead of approaching: Maintain a safe distance, especially from waterfowl and shorebirds.

- Disinfect gear: Clean boots, scopes, and feeders with a 10% bleach solution after outings.

- Suspend bird feeders if advised: Some states recommend removing feeders during peak migration periods when disease risk is highest.

- Wash hands thoroughly: Especially after outdoor activities near wetlands or lakes.

Organizations like the Audubon Society and eBird often post regional alerts about avian disease activity. Checking these before heading out enhances safety and supports citizen science efforts.

Debunking Common Misconceptions About Bird Flu Contagion

Several myths persist about how bird flu spreads. Clarifying these helps reduce unnecessary fear and promotes effective prevention.

| Myth | Fact |

|---|---|

| You can catch bird flu from eating chicken or eggs. | No—proper cooking (165°F/74°C) kills the virus. Avoid raw poultry products in outbreak zones. |

| Bird flu spreads easily between humans. | No evidence of sustained human-to-human transmission exists to date. |

| All dead birds indicate bird flu. | Many causes lead to bird mortality; testing is required for confirmation. |

| Pets like cats and dogs cannot get bird flu. | Rare cases have occurred, usually after consuming infected birds. |

Regional Differences in Risk and Response Strategies

The level of contagion and response varies significantly by region. In densely populated poultry regions like China's Guangdong province or parts of India and Bangladesh, frequent bird-human interaction increases spillover risk. In contrast, North America and Europe emphasize early detection and containment.

Europe experienced record-breaking H5N1 outbreaks in 2022–2023, affecting both wild and farmed birds. The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) responded with enhanced monitoring and temporary indoor confinement orders for poultry.

In Africa, surveillance systems are less developed, potentially underreporting cases. Meanwhile, Australia has remained largely free of HPAI due to geographic isolation and strict import controls.

Travelers to affected areas should check country-specific advisories from sources like the CDC or WHO. Those visiting live bird markets—common in parts of Asia—should wear masks and avoid touching surfaces unnecessarily.

Preparing for Future Outbreaks: What Individuals and Communities Can Do

Preparedness reduces panic and improves outcomes. Key steps include:

- Stay informed: Follow updates from trusted health and agricultural agencies.

- Support surveillance: Participate in reporting programs for dead or sick wildlife.

- Advocate for better farming practices: Encourage policies that reduce overcrowding and improve animal welfare.

- Stock emergency supplies: Households dependent on backyard poultry should have backup food sources and protective equipment.

- Promote One Health approaches: Recognize that human, animal, and environmental health are interconnected.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Can you get bird flu from watching birds in your backyard?

No, simply observing birds from a distance poses no risk. Transmission requires direct contact with infected secretions or tissues.

Is bird flu airborne?

It can be in enclosed spaces with high concentrations of infected birds, such as poultry houses. Open-air environments pose much lower risk.

Are migratory birds responsible for spreading bird flu globally?

Yes, wild waterfowl—especially ducks and geese—are natural carriers and play a major role in dispersing the virus along flyways.

Has bird flu ever caused a human pandemic?

No. While some strains have caused limited human infections, none have achieved efficient and sustained human-to-human transmission needed for a pandemic.

What should I do if I find a dead bird?

Do not touch it. Contact your local wildlife agency or department of natural resources for guidance on reporting and disposal.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4