Bird flu, also known as avian influenza, is primarily spread through direct contact with infected birds or their bodily fluids, such as saliva, nasal secretions, and feces. One of the most common ways how bird flu is spread is when healthy birds come into contact with contaminated environments—especially water, feed, or surfaces exposed to infected poultry. Wild birds, particularly migratory waterfowl like ducks and geese, often carry the virus without showing symptoms, making them silent transmitters across regions. This natural reservoir facilitates the widespread transmission of avian influenza viruses, especially during seasonal migrations. Understanding exactly how bird flu is spread helps farmers, wildlife managers, and public health officials implement effective biosecurity practices to reduce outbreaks in both domestic flocks and human populations.

The Biology of Avian Influenza Viruses

Avian influenza viruses belong to the Orthomyxoviridae family and are classified by two surface proteins: hemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N). There are 18 known H subtypes and 11 N subtypes, leading to various combinations such as H5N1, H7N9, and H5N8—all of which have caused significant outbreaks. These viruses mainly infect birds but can occasionally jump to mammals, including humans.

The virus replicates in the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts of birds. In highly pathogenic strains like H5N1, mortality rates in poultry can reach up to 90–100% within 48 hours of infection. Low-pathogenic strains may cause mild illness or go unnoticed, allowing undetected spread across farms and wild populations.

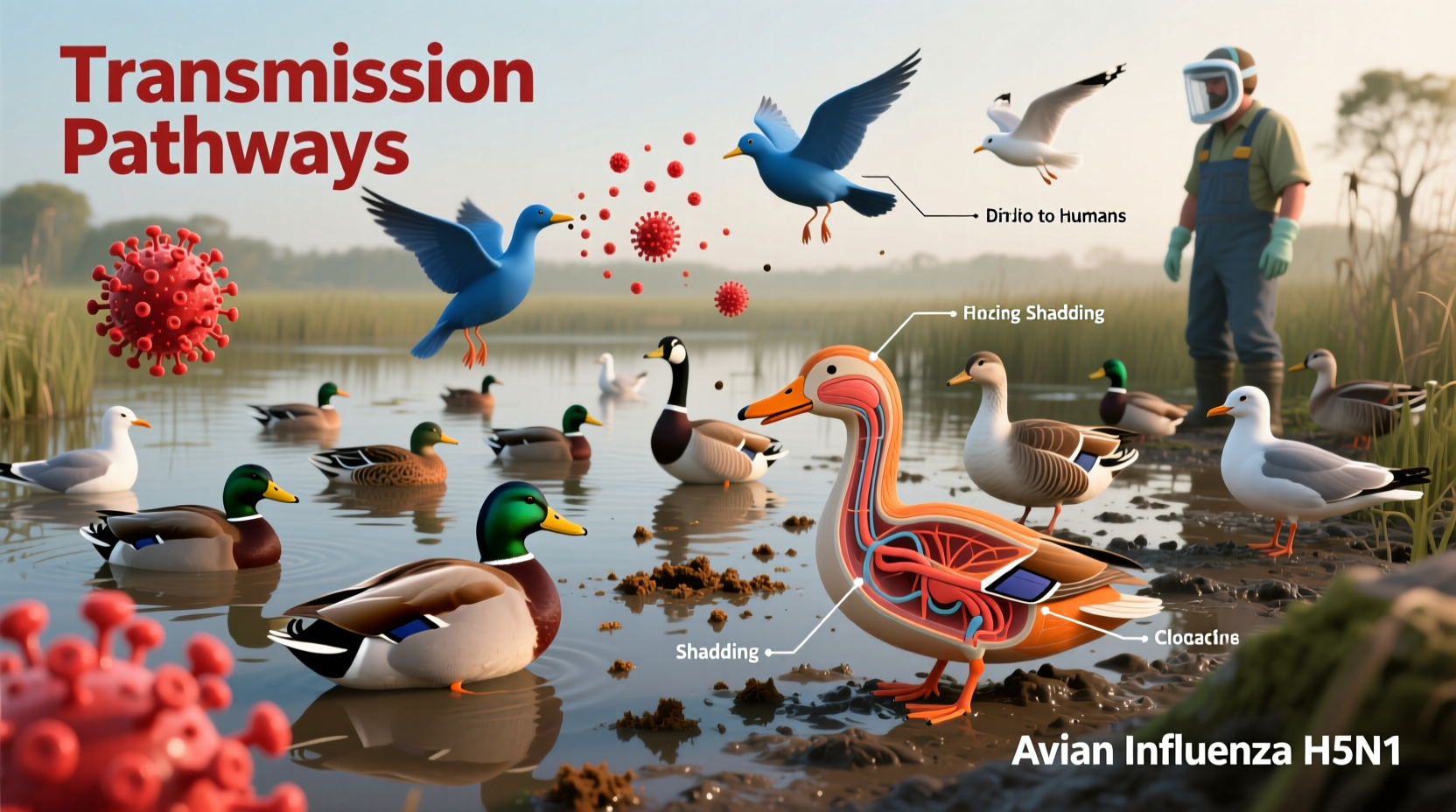

Primary Transmission Pathways: How Bird Flu Spreads Among Birds

The primary mode of transmission among birds involves close contact with infected individuals or exposure to contaminated environments. Key pathways include:

- Direct bird-to-bird contact: Especially in crowded conditions such as commercial poultry farms or live bird markets.

- Fecal-oral route: The virus is shed in large quantities through droppings, contaminating soil, water sources, and feeding areas.

- Aerosol transmission: In enclosed spaces, the virus can become airborne through dust or respiratory droplets.

- Migratory birds: Waterfowl act as long-distance carriers, introducing the virus to new wetlands, farms, and backyard flocks.

Water plays a critical role. Many avian influenza viruses remain infectious in cold water for over 30 days, posing a persistent risk to aquatic birds and those drinking from shared sources.

Human Exposure: Can People Catch Bird Flu?

While bird flu does not spread easily between humans, it can be transmitted from birds to people under certain conditions. Most human cases occur through prolonged, unprotected contact with infected birds or heavily contaminated environments.

High-risk activities include:

- Killing, plucking, or preparing infected poultry for cooking

- Working in live bird markets or on affected farms

- Handling sick or dead wild birds without gloves or masks

- Inhaling aerosolized particles in poorly ventilated poultry enclosures

Although rare, some strains like H5N1 and H7N9 have resulted in severe respiratory illness and fatalities in humans. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), since 2003, there have been over 900 confirmed human cases of H5N1 globally, with a case fatality rate exceeding 50%.

Can You Get Bird Flu From Eating Poultry or Eggs?

No, you cannot get bird flu from eating properly cooked poultry or eggs. The virus is destroyed at temperatures above 70°C (158°F). As long as meat reaches an internal temperature of at least 165°F (74°C) throughout, it is safe to consume.

However, cross-contamination remains a concern. Raw meat, feathers, or packaging materials can carry the virus. Always follow food safety practices:

- Wash hands thoroughly after handling raw poultry

- Use separate cutting boards for meat and vegetables

- Clean all utensils and surfaces with hot, soapy water

- Avoid consuming raw or undercooked eggs, especially in high-risk areas

Role of Wild Birds in Global Spread

Wild birds, especially migratory species, play a central role in the global dissemination of avian influenza. Species such as mallards, teals, swans, and geese often carry low-pathogenic forms of the virus asymptomatically. During migration, they travel thousands of miles, stopping at lakes, marshes, and agricultural fields where they interact with domestic birds.

Seasonal patterns influence outbreak timing. For example, increased detections in North America typically occur between late fall and early spring—coinciding with southward migrations. Surveillance programs monitor key stopover sites to detect early signs of viral presence.

In Europe and Asia, similar patterns have led to repeated introductions of H5N1 into commercial poultry operations, prompting mass culling and trade restrictions.

Domestic Poultry Farms: Hotspots for Outbreaks

Intensive farming systems create ideal conditions for rapid virus spread due to high bird density, limited genetic diversity, and frequent movement of animals and workers. Once introduced, the virus can move quickly through barns via:

- Contaminated footwear or clothing of farm personnel

- Shared equipment (feeders, waterers, crates)

- Vehicles transporting birds or supplies

- Pests such as rodents and flies that carry the virus on their bodies

To prevent this, strict biosecurity protocols are essential. Best practices include:

- Restricting access to poultry houses

- Providing dedicated clothing and boots for each facility

- Disinfecting vehicles and tools before entry

- Isolating new or returning birds for at least 30 days

- Monitoring flocks daily for signs of illness (lethargy, reduced appetite, swollen heads)

Urban and Backyard Flocks: Hidden Risks

Backyard poultry owners may underestimate their risk. Small flocks kept near wooded areas or ponds can come into contact with wild birds carrying the virus. Unlike commercial farms, many hobbyists lack formal training in disease prevention.

To protect backyard birds:

- Keep coops clean and dry

- Elevate feeders and waterers to avoid contamination

- Prevent wild birds from accessing shared resources

- Report sudden deaths or unusual symptoms to local veterinary authorities

- Register your flock if required by state or national regulations

Global Surveillance and Control Measures

Organizations like the WHO, the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), and the World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH) coordinate international efforts to track and respond to avian influenza outbreaks.

Key strategies include:

- Early detection through laboratory testing

- Rapid culling of infected and exposed birds

- Trade restrictions on poultry products from affected zones

- Vaccination programs in select countries (though controversial due to potential masking of infections)

- Public awareness campaigns targeting farmers and hunters

In the U.S., the USDA operates the National Poultry Improvement Plan (NPIP), which sets standards for disease control and provides diagnostic support during outbreaks.

Climate Change and Emerging Patterns in Bird Flu Spread

Emerging research suggests climate change may alter the dynamics of avian influenza transmission. Warmer temperatures and shifting precipitation patterns affect bird migration routes, breeding seasons, and habitat availability.

For instance, milder winters allow more birds to overwinter in northern latitudes, increasing local transmission windows. Changes in wetland ecosystems can concentrate bird populations around shrinking water sources, enhancing contact rates and viral spread.

Additionally, extreme weather events such as floods or droughts can disrupt normal migration, forcing birds into atypical areas where they interact with domestic flocks.

Common Misconceptions About How Bird Flu Is Spread

Several myths persist about avian influenza transmission. Clarifying these is crucial for accurate public understanding:

- Myth: Bird flu spreads easily from person to person.

Fact: Sustained human-to-human transmission has not been documented. Most cases involve direct bird contact. - Myth: All bird species are equally susceptible.

Fact: Chickens and turkeys are highly vulnerable; songbirds and raptors show variable resistance. - Myth: Only sick-looking birds carry the virus.

Fact: Infected birds may appear healthy, especially in early stages or with low-pathogenic strains. - Myth: Pet birds indoors are completely safe.

Fact: Airborne particles or contaminated items brought inside can pose risks, though minimal.

What Should You Do If You Find a Dead Bird?

If you discover a dead wild bird, especially waterfowl or multiple carcasses in one location, do not touch it with bare hands. Instead:

- Contact your local wildlife agency or department of natural resources

- Follow instructions for reporting and possible collection

- If advised to remove the bird, wear disposable gloves and use a plastic bag to pick it up

- Dispose of it in a sealed container with household waste (unless otherwise directed)

- Wash hands thoroughly afterward

Note: Some jurisdictions discourage public handling altogether and prefer professional assessment.

| Transmission Route | At-Risk Group | Prevention Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Contact with infected poultry feces | Farm workers, backyard keepers | Wear protective gear, sanitize boots and tools |

| Inhaling aerosols in poultry sheds | Poultry workers, veterinarians | Use masks, ensure ventilation |

| Handling dead wild birds | Hunters, birdwatchers, hikers | Use gloves, report findings |

| Consumption of undercooked meat | General public in outbreak zones | Cook poultry to 165°F internally |

| Contaminated water sources | Wild birds, free-range poultry | Provide clean drinking water, fence off ponds |

Future Outlook and Research Directions

Ongoing research focuses on improving diagnostics, developing universal avian influenza vaccines, and modeling outbreak risks using satellite tracking of bird movements. Scientists are also studying viral evolution to anticipate strains with higher zoonotic potential.

One promising area involves CRISPR-based gene editing to produce chickens resistant to avian influenza. While still experimental, such technologies could transform disease resilience in commercial flocks.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

How is bird flu transmitted from birds to humans?

Bird flu is transmitted to humans primarily through direct contact with infected birds or their droppings, especially during slaughter, defeathering, or cleaning coops. Inhalation of contaminated dust in enclosed spaces is another route.

Can bird flu spread through the air?

Yes, in confined spaces like poultry barns, the virus can become airborne in dust or respiratory droplets and infect nearby birds or humans. However, it does not spread efficiently through the air between people.

Is it safe to feed wild birds during an outbreak?

No, feeding stations can聚集 birds and increase transmission risk. Public health agencies often recommend suspending bird feeders in areas with confirmed avian influenza cases until the threat subsides.

Are certain bird species more likely to spread bird flu?

Yes, waterfowl—especially ducks, geese, and swans—are natural reservoirs of avian influenza and can carry and spread the virus without showing symptoms.

What should poultry farmers do during a bird flu outbreak?

Farmers should enhance biosecurity, restrict visitor access, monitor flocks daily, report suspicious deaths immediately, and comply with quarantine orders. Vaccination may be considered in consultation with veterinary authorities.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4